The Partridge That Fooled the PAF: The IAF’s Aerial Ghost

In a recent faceoff, the Indian Air Force unleashed ghost jets—pilotless drones mimicking Rafales and Su-30s—that lit up Pakistan’s air defences. But this stunning decoy tactic has roots in 1940s cloth banners. This is the untold story of IAF’s evolution—from canvas to combat deception.Anchit Gupta

May 20, 2025

16 minutes

106 Sqn, 1971 War, 224 Sqn, Canberra, Dakota, Hunter, Indigenisation IAF, Jamnagar, Kalaikunda, MiG-23, Tempest, Toofani, Vengeance

In the high-stakes chess match of India-Pakistan aerial conflict, sometimes the most decisive piece isn’t a fighter jet—it’s a ghost.

Recently, the Indian Air Force executed a brilliant sleight of hand in the skies. Employing advanced remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs), these drones didn’t carry weapons—they carried deception. Programmed meticulously to emulate the electronic and radar signatures of frontline IAF fighters, such as the Rafale, Su-30MKI, and MiG-29, these drones provoked a full-scale response from Pakistan’s air defence networks. Radars illuminated, missile batteries activated, and interceptors scrambled—all chasing targets that weren’t real.

Yet, this sophisticated digital deception did not emerge overnight. Its roots extend back nearly a century, beginning humbly in 1941 when IAF pilots first towed cloth banners behind lumbering aircraft—simple decoys for gunners below. This is the rarely told story of the Indian Air Force’s decoy doctrine, which could deceive entire air defence systems.

Canvas in the Wind: The Target Towing Origins

The Indian Air Force’s journey into aerial deception began not with radar jammers or sophisticated countermeasures, but with something far simpler—canvas.During World War II, the need arose to train anti-aircraft gunners realistically. Anti-aircraft cooperation Flights were formed across India to meet this, towing large canvas banners behind aircraft as moving targets. The first such flight began operations at Karachi on 15 July 1941, soon followed by units at Juhu (21 January 1942) and Dum Dum (20 March 1942). The early aircraft—Wapitis, Harlows, Lysanders, Moth Minors, and Tiger Moths—were reliable, if unspectacular, machines of their era.

By 1942, as wartime demands intensified, these flights merged into No. 22 Anti-Aircraft Cooperation Unit (AACU), established on 3 December at Drigh Road, Karachi. Consolidating further with flights at Deolali and Dum Dum by March 1943, 22 AACU became the principal banner-towing unit across British India. By 1946, operating from Santa Cruz, its fleet had expanded impressively, including Hurricanes, Blenheims, Fairey Battles, Marylands, Buffalos, Vengeances, Defiants and Beaufighters.

Yet, the task was perilous. Young Indian pilots often faced daunting conditions. Tragedies like Pilot Officer Charan Das Sharma’s fatal crash into the Bandra Sea and Pilot Officer Arthur Joseph’s deadly accident near Katni in May 1944 underline the hazards, with at least 53 crashes recorded in this demanding support role.

Partition brought with it disruption and a transition. The unit’s flights were reorganised as No. 1 and No. 2 Target Towing Flights (TTF), flying Vengeance aircraft out of Drigh Road and Poona, respectively. However, both were shut down by August 1947 due to the turmoil of the times.

Rebirth at Jamnagar

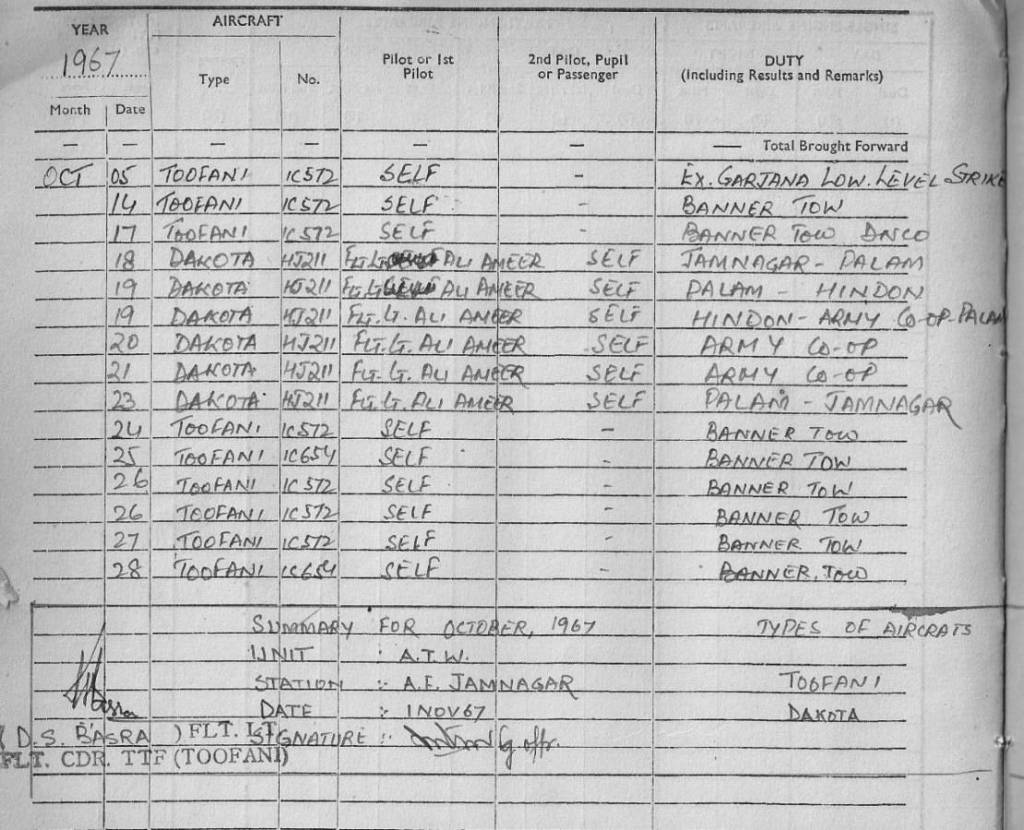

In 1951, banner towing resumed at the newly formed Armament Training Wing (ATW) at Jamnagar with the Target Towing Flight. Initially, Dakotas painted in distinctive yellow for visibility were used to tow banners for the Air Force, Army artillery, and Navy coastal batteries.The targets were canvas sleeves, resembling oversized windsocks, trailing behind the aircraft. This simple yet effective setup allowed fighter pilots and anti-aircraft gunners to practice live firing on moving airborne targets. A novel attempt was made to install a 25-pound acoustic sensor device on the sleeve to record hits electronically. Still, this innovation met a dramatic end—it was destroyed by a direct hit during its maiden run.

Instead, a more low-tech but ingenious method was used to assess accuracy. The tips of the bullets were dipped in different coloured paints—red, green, black—corresponding to each shooter. After the sortie, the sleeve was inspected, and the colour of the bullet holes revealed who had scored hits, and how many.

Hawker Tempests—a rugged, ex-fighter aircraft that has now been repurposed with an underbelly hook for target towing, was added in 1954. In 1955, the unit transitioned into the jet age with Dassault Toofanis, followed by Mystère IVAs in the late 1960s. Around 1972, the TTF moved to Kalaikunda (KKD)—a shift driven by safer access to air-to-air and air-to-sea ranges. This move also introduced Hawker Hunters, which served the unit faithfully until its final operational years.

During the 1971 war, the TTF transcended its support role. Redesignated as No. 120 Ad-hoc Squadron under the command of Squadron Leader V.N. Johri, it operated from Nal and conducted tactical reconnaissance and disruption missions deep into enemy territory. The unit destroyed railyards, munitions dumps, and oil facilities, earning four Vir Chakras and one Vishisht Seva Medal.

Expansion and Modernisation

The 1960s saw the TTF’s mission continue to expand to support Navy and Army anti-aircraft training. This led to the creation of two specialised units in May 1969: No. 1 Target Towing Unit (TTU) at Cochin for naval support, and No. 2 TTU at Palam for the Army, formed from the Dakotas of the TTF flight.

In June 1985, No. 1 TTU was re-equipped with Canberra B(I)58s and relocated to Pune. No. 2 TTU was reformed on 23 November 1987 at Agra, also with Canberras. With this shift, both units transitioned from Army/Navy target towing to air-to-air banner target towing, supporting fighter aircraft of both the IAF and Indian Navy.

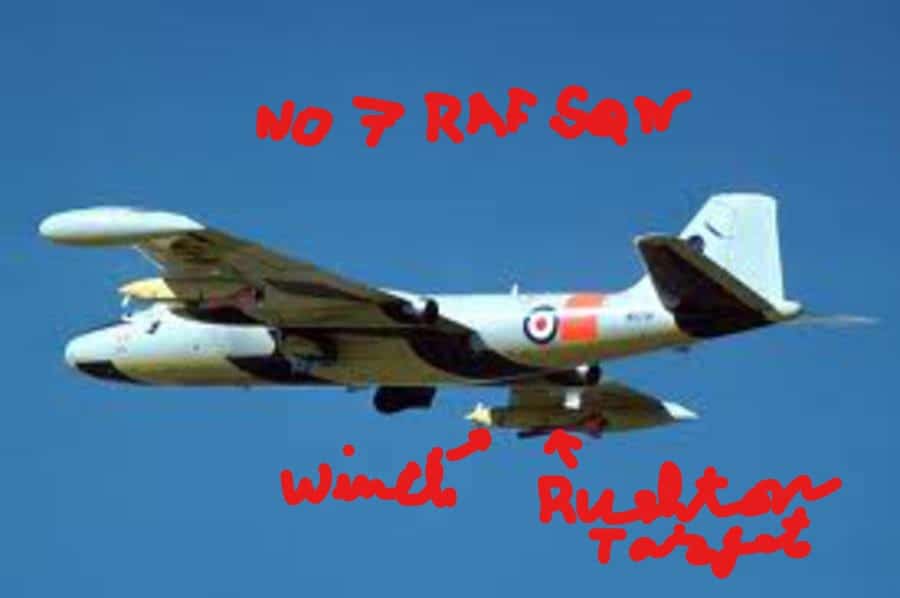

In parallel, No. 6 Squadron was equipped in 1979 with Canberra TT-418s fitted with pylon-mounted Rushton winch packs and took on the banner towing role for air defence training across the three services.

In June 1992, these entities—1 TTU, 2 TTU, and the No. 6 Squadron flight—merged into a single TTU at Agra. Banner towing operations officially ceased by 1996, and the unit was absorbed into 106 Squadron the following year. When the Canberras were phased out in 2007, A Flight of 106 Squadron continued operations with HS748s and was renamed the Survey and Target Towing Unit (STTU), before disbanding a few years later.

While Kalaikunda-based Hawker Hunters continued towing banners until 2002, another frontline aircraft, the MiG-23, joined this role with No. 224 Squadron from the 1990s until 2007. Specially modified MiG-23s towed 9×3 metre banners, painted bright orange for visibility, trailing them on 320-metre cables. This critical peacetime training enhanced fighter pilots’ live-fire accuracy, marking the end of traditional banner towing.

With that, the age of canvas finally gave way to silicon and sensors. But the legacy of banner towing lives on—in every pilot who once aimed at a fluttering target in the sky, in every squadron that perfected its gunnery through this quiet but vital tradition of skill-building in the air.

Precision From the Pylons – Rushton & TT-418

By the late 1970s, traditional cloth banners were becoming insufficient for realistic training against modern radar-guided missile systems. To address this evolving need, the Indian Air Force turned to the sophisticated Rushton Target Towing System and a specially modified fleet of Canberra bombers.Drawing inspiration from the Royal Air Force, India acquired six former RAF Canberra T.4 aircraft and extensively modified them into the Canberra TT-418 variant. Central to this transformation was the Rushton winch system, installed on pylons beneath the wings, which enabled the aircraft to deploy and retrieve radar-reflective targets mid-flight—an engineering breakthrough that turned these Canberras into flying radar simulators.

The Rushton system featured highly advanced targets, equipped with acoustic miss-distance indicators capable of precisely measuring how closely missiles or shells passed by. Additionally, radar enhancement lenses made these targets convincingly replicate the radar signature of actual combat aircraft. These targets could be extended to an impressive 20,000 feet behind Canberra, providing a realistic missile and gun training scenario. Unlike simpler target systems, these sophisticated targets were recoverable mid-flight, offering repeated use.

Alongside the Rushton targets, the sleeve targets—simpler, elongated fabric structures resembling windsocks—were also used. While lacking electronic sophistication, sleeves provided effective visual and radar-reflective training aids. Typically extended to 2,000 feet, they were jettisoned after exercises and retrieved manually at designated drop zones.

In 1978, recognising the complexity of operating these new systems, the IAF sent four navigators to RAF St. Mawgan’s No. 7 Squadron for specialised training. These navigators became expert airborne winch operators, mastering the intricate art of deploying, managing, and retrieving cable and target systems mid-air.

The newly operational TT-418 fleet became part of ‘C Flight’ of No. 6 Squadron at Agra, taking over critical banner-towing duties for the IAF’s frontline fighter pilots. Their missions extended beyond the Air Force, supporting Army anti-aircraft exercises involving the L-60, L-70, and Shilka systems, and Navy tests for Sea Cat missiles conducted off India’s western coastline near Murud Janjira.

Operating these Canberra aircraft required exceptional skill. Pilots faced significant aerodynamic challenges, as the 20,000-foot cable and missile-shaped target affected the aircraft’s stability, control, and fuel consumption. Navigators and winch operators closely monitored cable oscillations, radar visibility, and acoustic feedback, demanding constant vigilance and precision.

The Chakor Era – India’s First RPAs

As missile systems advanced and training needs evolved, the IAF required something safer and more sophisticated than crewed aircraft pulling targets. This necessity catalysed India’s first serious venture into remotely piloted aircraft: the Chakor (Indian name for partridge).The name “Chakor” is more than just symbolic. In North Indian and Pakistani folklore and Hindu mythology, the chakor is known for its unrelenting, often unrequited love for the moon—an enduring metaphor for aspiration, pursuit, and longing. Aptly named, the Chakor RPV represented India’s aspirational leap into unmanned aerial systems.

The idea took shape in 1976, when the IAF formalised its Pilotless Target Aircraft (PTA) requirement. By 1978, this vision took flight at Kalaikunda with the raising of the Chakor PTA Squadron. Operationally, Chakor was the Indian designation for the Northrop MQM/BQM-74 Chukar—a subsonic, turbojet-powered aerial target drone widely used by the U.S. Navy.

Compact yet potent, the Chakor had a wingspan of 1.5 metres, weighed under 200 kilograms, and could reach speeds exceeding 900 km/h. Its jet propulsion and radar signature made it ideal for realistic air defence training—far more dynamic than the static cloth banners of previous decades.

Air Marshal Bhojwani, a veteran of these training sorties, recalled how Kalaikunda-based detachments had begun incorporating live-firing exercises against these unmanned targets, dramatically improving realism and pilot proficiency.

Yet, for all its advantages, the Chakor had limitations. As an imported system, maintaining it was costly and entirely dependent on foreign suppliers. Moreover, it was used exclusively by the IAF—it was never adapted for naval or ground-based air defence roles.

Still, the Chakor had done its job. It marked India’s operational entry into the RPA domain, years before the term “drone” became commonplace. It trained pilots to aim at jet-propelled, radar-reflective targets. Most importantly, it laid the groundwork for a future where unmanned systems wouldn’t just be targets but strategic assets.

By the mid-1990s, however, the Chakor was becoming unsustainable. As India prepared to induct its indigenous Lakshya PTA, the Chakor squadron was reorganised in 1998 as ‘A’ Flight within Kalaikunda’s TTF, just before the Chakor and the last Hunter aircraft were retired.

Lakshya – India’s Indigenous Triumph

As India’s defence strategy pivoted toward self-reliance in the 1980s, the limitations of foreign-made systems like the Chakor became apparent. The IAF needed an indigenous remotely piloted target, leading to the birth of the Lakshya Pilotless Target Aircraft.Sanctioned in September 1980, the Lakshya program was led by the Aeronautical Development Establishment (ADE) of DRDO, with Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) responsible for developing the propulsion system. Lakshya was powered by a Microturbo TRI-60-5 turbojet engine, designed to be high-subsonic and reusable.

Development was anything but smooth. The first flight trials began in December 1985, and of the four initial flights in 1986, only two succeeded. The early years were marked by trial, error, and persistence. Between 1985 and 1990, 10 prototypes were lost, but the ADE team persisted. By June 1994, 18 prototypes had been built, and 43 test flights had been conducted.

Development concluded in June 1994, and by 1998, six operational Lakshya drones were deployed at Kalaikunda, replacing the ageing Chakor RPVs and the last of the Hunter tow aircraft. The formal induction occurred on 9 November 2000 at Chandipur’s Integrated Test Range, with Air Chief Marshal A.Y. Tipnis presiding.

Technologically advanced, Lakshya featured jet propulsion, autonomous pre-programmed mission paths, and a zero-length booster launch system. It could execute varied flight profiles—racetrack, dog bone, or snake track—with designated zones for missiles or guns to engage.

At about Mach 0.53, Lakshya was fast enough to emulate real aerial threats. It was recoverable via parachute, with a crushable nose cone that absorbed landing impact. Its modular design allowed damaged parts to be quickly replaced, significantly lowering lifecycle costs.

Its standout feature, however, was its ability to tow two expendable sub-targets equipped with infrared or radio-frequency signature enhancers. These made the Lakshya detectable to heat-seeking and radar-guided systems, enabling realistic training scenarios. Some sub-targets even used Doppler-based scoring systems to record near misses, akin to the Rushton tech used earlier with Canberras.

Lakshya’s hallmark was versatility. It supported all three services: simulating cruise missiles for the Navy, aircraft targets for Army air defence, and high-fidelity training and missile evaluation for the IAF.

In May 2002, an upgraded version flew with an indigenous HAL-developed turbojet, achieving complete propulsion self-reliance. By November 2002, HAL received its first order for 25 units, and limited series production began.

By January 2003, Lakshya had completed over 100 operational flights, proving its dependability. Later enhancements included passive jamming, signature manipulation, and swarm simulation capabilities.

Lakshya had achieved what Chakor could not: it was home-grown, multi-service, and built to evolve. It remained operational for nearly two decades, a quiet but powerful symbol of India’s progress in unmanned aviation.

Banshee – RPAs as Electronic Decoys

If Lakshya symbolised India’s triumph in indigenous target drone development, the Banshee marked the IAF’s bold leap into tactical electronic deception.By the 2010s, air defence had evolved into a contest of perception as much as firepower. The challenge was no longer just engaging what you saw, but determining whether what you saw was real. In this rapidly shifting battlespace, the Banshee emerged as a game-changer: part aerial target, part electronic warfare platform, and part decoy.

Developed by Meggitt Defence Systems, the Banshee was an internationally recognised aerial target drone, prized for its modular design and adaptability across various mission profiles. India acquired multiple variants, including the Banshee Jet 40+, which introduced jet propulsion, greater payload capacity, and advanced electronic countermeasure (ECM) capabilities.

Despite its compact dimensions—73 kg in weight, a 2.5-metre wingspan, and 3 metres in length—the Banshee packed immense versatility. It offered a 75-minute flight endurance, could reach altitudes of 23,000 feet, and cruised at 200 km/h. But speed wasn’t its strongest suit—simulation was. Outfitted with radar augmentation pods, IR flares, or ECM jammers, the Banshee could convincingly mimic a wide range of aerial threats.

Operational deployment began with No. 3041 Squadron, where Banshees became central to integrated training at the IAF’s gunnery ranges network. But soon, their purpose evolved. With thoughtful adaptation, the Banshee transformed into an airborne decoy capable of mimicking India’s frontline fighters’ radar and heat signatures, such as the Su-30MKI, Rafale, Jaguar, and MiG-29. The Banshee Jet 40+ was particularly valued for its ability to emulate fast-jet characteristics with surprising fidelity.

India’s next step was to go local. As per a PIB release, under the Ministry of Defence’s Make-II program, Anadrone Systems secured a landmark contract to supply 125 Manoeuvrable Expendable Aerial Targets (MEAT), built around its Shikra platform—an Indian evolution of the Banshee Jet 40. By 2024, Anadrone, in collaboration with QinetiQ Target Systems of the UK, had delivered over 600 aerial targets, marking a significant milestone in India’s electronic warfare capability.

The impact of these systems became clear during recent tensions with Pakistan. The IAF is supposed to have launched multiple RPAs designed to mimic manned aircraft behaviour. Outfitted with radar signature enhancers and electronic beacons, these drones appeared on Pakistani radar as real fighters. Enemy sensors lit up. Air defence radars were activated, SAM batteries were powered on, and interceptors were scrambled.

Meanwhile, the IAF silently observed from a distance, recording radar frequencies, pinpointing SAM locations, and mapping defensive responses in real time. No manned aircraft crossed the border, and no pilot was at risk. Yet, entire enemy air defence grids were exposed.

In those moments, the Banshee was no longer a target. It was bait.

Epilogue: From Banners to Bait

What began with Wapiti towing cloth banners is now an integral part of India’s electronic warfare doctrine. The IAF’s journey—from fabric to fibre optics, cable to code—is a story of innovation, patience, and tactical foresight.From Chakor to Lakshya, from Canberras with Rushton winches to Shikras simulating fighter squadrons, each step in this journey has refined the art of deception and defence. The shift from training aids to electronic decoys mirrors the evolution of aerial warfare, where the first move is not to strike, but to be seen striking.

The humble Chukar, which once flew as just another partridge-shaped blip on radar, has become a key player in complex electronic baiting operations. It has helped write a new rulebook: don’t just train the shooter—fool the sensor. And so, what began with banners now ends with bait. But the mind behind the machine? That, as always, remains human.

I am thankful to the scores of veterans who contributed to the research as well as the brotherhood of Desi Aviation Nerds

Credit: Anchit Gupta, IAF Historian

Source: The Partridge That Fooled the PAF: The IAF’s Aerial Ghost

@Lulldapull @Sharma Ji @Guru Dutt @Krishna with Flute @Mainerik @Israel Person @Saif @VCheng @Jiangnan

Last edited: