Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,117

- Likes

- 8,060

- Nation

- Axis Group

Challenges in export diversification

To sustain the upward trajectory of exports, expanding the range of products in our export basket is essential. The country's foreign exchange reserves are under significant pressure due to inconsistencies in export earnings, which have a ripple effect on import payments and broader macroeconomic f

Challenges in export diversification

Abu Mukhles Alamgir Hossain

Published :

Oct 24, 2024 21:27

Updated :

Oct 24, 2024 21:27

To sustain the upward trajectory of exports, expanding the range of products in our export basket is essential. The country's foreign exchange reserves are under significant pressure due to inconsistencies in export earnings, which have a ripple effect on import payments and broader macroeconomic factors. Over the years, leading economists, think-tanks and industry experts have consistently emphasised the need for export diversification to ensure sustainable international trade. However, little progress has been made on this much-discussed issue. The reasons behind the lack of diversification are well-known.

DEPENDENCY ON A SINGLE SECTOR: Bangladesh's export trade is heavily dependent on the apparel sector, which contributes 84 per cent of the country's export earnings. This sector receives substantial support from the government, including cash incentives, bonded warehouse facilities, easy bank financing, and policy interventions during times of difficulty. The ready-made garments (RMG) sector benefits from lower production costs and large-scale employment, creating a disincentive for exploring and developing other sectors. The sector's contribution over the last five years is as follows:

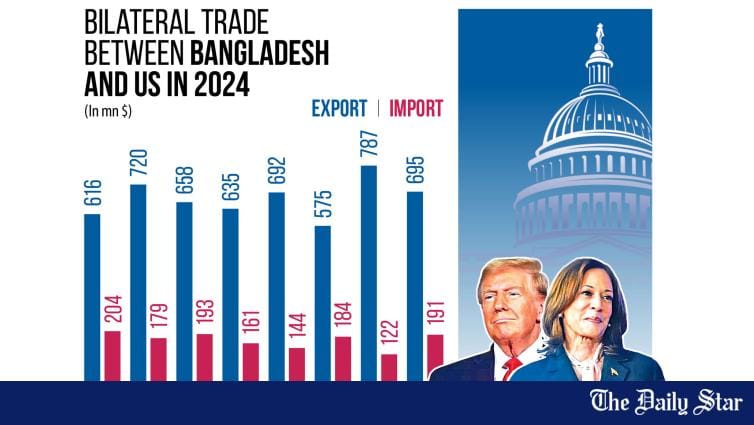

EXPORT DESTINATIONS VULNERABILITY: The United States and the European Union are the two primary export destinations for Bangladeshi products. Collectively, the EU represents the largest export market, followed by the USA as the second largest. These two destinations account for 44 per cent and 17 per cent of Bangladesh's total exports, respectively, while the rest of the world makes up 39.02 per cent. The following graph highlight the concern:

Bangladesh's excessive dependence on the USA and EU makes its exports highly vulnerable. To reduce this over-reliance, it is crucial to explore and expand into new markets, such as Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and other regions of North America.

POTENTIAL SECTORS NOT RECEIVING THE SAME SUPPORT AS RMG: Other potential sectors, such as Leather and Leather Goods, Jute and Jute Goods, Agricultural and Processed Products, Handicrafts, Pharmaceuticals, ICT and ICT-enabled services, and Light Engineering Products do not receive the same level of support as the RMG sector. Sector-specific policy papers are needed to evaluate the pros and cons of their impact on the economy, while also considering the approaches of competing countries. The export performance of the Non-RMG products are as follows:

POLICY-INDUCED ANTI-EXPORT BIAS: Domestic manufacturers enjoy government-imposed protectionism through higher import duties, which diminishes the competitiveness of local industries against foreign products. Due to the domestic market's convenience, manufacturers are often disincentivised to export as they avoid the compliance and standards required for the global market. Dependency on import tariffs for revenue collection is another crucial factor hindering export diversification. Bangladesh is going to be graduating in November 2026 to a middle-income country, so to sustain growth and expand export destinations, there is the crucial need to liberalise international trade by considering the signing of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) or Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with potential countries and economic blocs.

LOW TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENT: Limited technological know-how and poor integration of technology hinder the growth of high-tech industries. Bangladesh's reliance on labour-intensive manufacturing restricts its ability to compete in technology-driven sectors, such as electronics. To diversify exports into the high-tech industry, Bangladesh must invest in ICT (bridging the digital divide), skill upgrading, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education, innovation hubs, and intellectual property protection. A prompt action plan should be formulated by relevant authorities, with a focus on timely implementation to maximise benefits.

INCONSISTENT TRADE POLICIES: Trade policies are often inconsistent and overly complex, creating a challenging environment for businesses to invest in new sectors. Delays in implementing reforms and a lack of long-term policy support for non-RMG sectors discourage investment.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND COMPLIANCE ISSUES: Sustainable production and compliance with global environmental standards are becoming increasingly important, especially in sectors like textiles, leather, and agriculture products. The lack of compliance makes it harder for Bangladesh to tap into eco-friendly markets or export to countries with strict regulations. Despite its significant potential, the leather sector in Bangladesh faces challenges hindering its growth. The CETP in the Saver Leather Industrial Park is not operating effectively, hindering environmental sustainability. LWG certification, essential for attracting reputable buyers, is difficult to obtain due to the park's environmental issues. Sourcing rawhide from slaughterhouses is another challenge, as the skin is often handled by unskilled or semiskilled butchers. The plastic sector also struggles to meet global standards for recycling. Despite its vast potential, it faces limitations in capturing a substantial share of the world market. Similarly, the agriculture and textile sectors encounter obstacles in tapping into international markets due to compliance challenges.

SKILL SHORTAGES: Diversifying exports requires a workforce with specialised skills in various industries. Leather, Jute, Handicrafts, Home décor, Cosmetics, Light Engineering, and ICT sectors need skills and expertise in which we are struggling. Investing in training and development programmes is crucial to equip the workforce with the necessary skills.

LIMITED INNOVATION AND RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT (R&D): There is a limited focus on R&D, which is crucial for product and process innovation in non-traditional export sectors. Investment in innovation is low, and there is little collaboration between the private sector, academic institutions, and government bodies which needs to be enhanced. High Tech Industry needs Research and Development (R&D) with the utmost priority. To overcome these challenges, Bangladesh must increase investment in R&D, fortify intellectual property protection, invest in human capital development, streamline regulatory processes, and improve market access. By fostering a more supportive environment for innovation, Bangladesh can diversify its exports and become a more competitive player in the global economy.

LACK OF LOGISTICS: Insufficient facilities across the three modes of export shipments-air, sea, and land-are lagging compared to other competing countries. Ports in Bangladesh face issues such as inefficient cargo handling, insufficient Explosive Detection Scanners (EDS), fluctuating spot air freight prices, inadequate warehouse and cargo village facilities, and a shortage of skilled and semi-skilled manpower. As a result, exporters are unable to fully capitalise on opportunities to diversify their exports.

GLOBAL COMPETITION: Bangladesh faces stiff competition from countries like Vietnam, India, and Cambodia in diversified sectors such as electronics, leather goods, and IT services. Low brand recognition and a lack of quality standards make it hard for Bangladeshi products to penetrate new international markets. In addition, after graduating to a middle-income country in 2026, Bangladesh will no longer be able to utilise unilateral preferential market access facilities, which will further weaken our competitiveness.

LIMITED ACCESS TO FINANCE SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES (SMES): SMEs often face difficulties in accessing affordable credit. High interest rates, lack of required collateral discourage entrepreneurs from expanding into new sectors. As the lifeblood of the economy, SMEs must be prioritised if Bangladesh is determined to diversify its export basket. In this case, Japan's lesson/success story can be followed by Bangladesh.

Export diversification cannot happen overnight, and there is no shortcut to achieving it. Long-term strategies, sector-specific policies, business-friendly customs procedures, and efficient logistics must be ensured to diversify our export sector.

Abu Mukhles Alamgir Hossain, Director (Policy and Planning), Export Promotion Bureau (EPB).

Abu Mukhles Alamgir Hossain

Published :

Oct 24, 2024 21:27

Updated :

Oct 24, 2024 21:27

To sustain the upward trajectory of exports, expanding the range of products in our export basket is essential. The country's foreign exchange reserves are under significant pressure due to inconsistencies in export earnings, which have a ripple effect on import payments and broader macroeconomic factors. Over the years, leading economists, think-tanks and industry experts have consistently emphasised the need for export diversification to ensure sustainable international trade. However, little progress has been made on this much-discussed issue. The reasons behind the lack of diversification are well-known.

DEPENDENCY ON A SINGLE SECTOR: Bangladesh's export trade is heavily dependent on the apparel sector, which contributes 84 per cent of the country's export earnings. This sector receives substantial support from the government, including cash incentives, bonded warehouse facilities, easy bank financing, and policy interventions during times of difficulty. The ready-made garments (RMG) sector benefits from lower production costs and large-scale employment, creating a disincentive for exploring and developing other sectors. The sector's contribution over the last five years is as follows:

EXPORT DESTINATIONS VULNERABILITY: The United States and the European Union are the two primary export destinations for Bangladeshi products. Collectively, the EU represents the largest export market, followed by the USA as the second largest. These two destinations account for 44 per cent and 17 per cent of Bangladesh's total exports, respectively, while the rest of the world makes up 39.02 per cent. The following graph highlight the concern:

Bangladesh's excessive dependence on the USA and EU makes its exports highly vulnerable. To reduce this over-reliance, it is crucial to explore and expand into new markets, such as Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and other regions of North America.

POTENTIAL SECTORS NOT RECEIVING THE SAME SUPPORT AS RMG: Other potential sectors, such as Leather and Leather Goods, Jute and Jute Goods, Agricultural and Processed Products, Handicrafts, Pharmaceuticals, ICT and ICT-enabled services, and Light Engineering Products do not receive the same level of support as the RMG sector. Sector-specific policy papers are needed to evaluate the pros and cons of their impact on the economy, while also considering the approaches of competing countries. The export performance of the Non-RMG products are as follows:

POLICY-INDUCED ANTI-EXPORT BIAS: Domestic manufacturers enjoy government-imposed protectionism through higher import duties, which diminishes the competitiveness of local industries against foreign products. Due to the domestic market's convenience, manufacturers are often disincentivised to export as they avoid the compliance and standards required for the global market. Dependency on import tariffs for revenue collection is another crucial factor hindering export diversification. Bangladesh is going to be graduating in November 2026 to a middle-income country, so to sustain growth and expand export destinations, there is the crucial need to liberalise international trade by considering the signing of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) or Free Trade Agreements (FTA) with potential countries and economic blocs.

LOW TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENT: Limited technological know-how and poor integration of technology hinder the growth of high-tech industries. Bangladesh's reliance on labour-intensive manufacturing restricts its ability to compete in technology-driven sectors, such as electronics. To diversify exports into the high-tech industry, Bangladesh must invest in ICT (bridging the digital divide), skill upgrading, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education, innovation hubs, and intellectual property protection. A prompt action plan should be formulated by relevant authorities, with a focus on timely implementation to maximise benefits.

INCONSISTENT TRADE POLICIES: Trade policies are often inconsistent and overly complex, creating a challenging environment for businesses to invest in new sectors. Delays in implementing reforms and a lack of long-term policy support for non-RMG sectors discourage investment.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND COMPLIANCE ISSUES: Sustainable production and compliance with global environmental standards are becoming increasingly important, especially in sectors like textiles, leather, and agriculture products. The lack of compliance makes it harder for Bangladesh to tap into eco-friendly markets or export to countries with strict regulations. Despite its significant potential, the leather sector in Bangladesh faces challenges hindering its growth. The CETP in the Saver Leather Industrial Park is not operating effectively, hindering environmental sustainability. LWG certification, essential for attracting reputable buyers, is difficult to obtain due to the park's environmental issues. Sourcing rawhide from slaughterhouses is another challenge, as the skin is often handled by unskilled or semiskilled butchers. The plastic sector also struggles to meet global standards for recycling. Despite its vast potential, it faces limitations in capturing a substantial share of the world market. Similarly, the agriculture and textile sectors encounter obstacles in tapping into international markets due to compliance challenges.

SKILL SHORTAGES: Diversifying exports requires a workforce with specialised skills in various industries. Leather, Jute, Handicrafts, Home décor, Cosmetics, Light Engineering, and ICT sectors need skills and expertise in which we are struggling. Investing in training and development programmes is crucial to equip the workforce with the necessary skills.

LIMITED INNOVATION AND RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT (R&D): There is a limited focus on R&D, which is crucial for product and process innovation in non-traditional export sectors. Investment in innovation is low, and there is little collaboration between the private sector, academic institutions, and government bodies which needs to be enhanced. High Tech Industry needs Research and Development (R&D) with the utmost priority. To overcome these challenges, Bangladesh must increase investment in R&D, fortify intellectual property protection, invest in human capital development, streamline regulatory processes, and improve market access. By fostering a more supportive environment for innovation, Bangladesh can diversify its exports and become a more competitive player in the global economy.

LACK OF LOGISTICS: Insufficient facilities across the three modes of export shipments-air, sea, and land-are lagging compared to other competing countries. Ports in Bangladesh face issues such as inefficient cargo handling, insufficient Explosive Detection Scanners (EDS), fluctuating spot air freight prices, inadequate warehouse and cargo village facilities, and a shortage of skilled and semi-skilled manpower. As a result, exporters are unable to fully capitalise on opportunities to diversify their exports.

GLOBAL COMPETITION: Bangladesh faces stiff competition from countries like Vietnam, India, and Cambodia in diversified sectors such as electronics, leather goods, and IT services. Low brand recognition and a lack of quality standards make it hard for Bangladeshi products to penetrate new international markets. In addition, after graduating to a middle-income country in 2026, Bangladesh will no longer be able to utilise unilateral preferential market access facilities, which will further weaken our competitiveness.

LIMITED ACCESS TO FINANCE SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES (SMES): SMEs often face difficulties in accessing affordable credit. High interest rates, lack of required collateral discourage entrepreneurs from expanding into new sectors. As the lifeblood of the economy, SMEs must be prioritised if Bangladesh is determined to diversify its export basket. In this case, Japan's lesson/success story can be followed by Bangladesh.

Export diversification cannot happen overnight, and there is no shortcut to achieving it. Long-term strategies, sector-specific policies, business-friendly customs procedures, and efficient logistics must be ensured to diversify our export sector.

Abu Mukhles Alamgir Hossain, Director (Policy and Planning), Export Promotion Bureau (EPB).