Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 15,919

- Likes

- 7,996

- Nation

- Axis Group

Govt plans ‘fibre optic bank’ to use idle networks

The government has decided to establish a national “fibre optic bank”, which will bring all unused fibre optic resources from state-owned entities under a single platform in a bid to accelerate digital transformation.

Govt plans ‘fibre optic bank’ to use idle networks

The government has decided to establish a national "fibre optic bank", which will bring all unused fibre optic resources from state-owned entities under a single platform in a bid to accelerate digital transformation.

The telecom and ICT divisions have officially invited Bangladesh Railway and the Power Grid Company of Bangladesh (PGCB) to join this fibre-sharing consortium, alongside Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited (BTCL) and Bangladesh Computer Council (BCC).

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb, special assistant to the chief adviser with executive authority over the Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and Information Technology, recently sent a letter to Railways and Power Adviser Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan, outlining the government's vision for this initiative and urging participation.

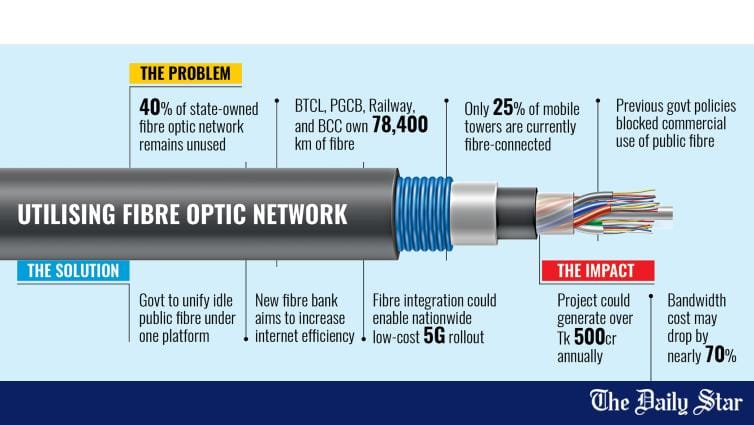

40% OF PUBLIC FIBRE NETWORKS REMAIN UNUSED

The letter, seen by The Daily Star, states that over the past decade, different government agencies have installed thousands of kilometres of optical fibre—much of which remains underutilised or completely idle.

The letter notes that, in total, BTCL, PGCB, Railway, and BCC own 78,400 kilometres (km) of fibre network. Of this, an estimated 40 percent remains unused.

"We are wasting a vital national asset by leaving large portions of optical fibre unused. It's time we came together and built a centrally managed, transparent, and efficient fibre ecosystem for all," Taiyeb said.

He also said Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus has verbally endorsed the plan, enabling the Posts and Telecom Division to formally invite PGCB and Bangladesh Railway to the consortium.

"This is not just about connectivity. It's about bringing digital transformation where every union has high-speed access and every public resource is optimally used," he added.

Taiyeb's letter to Adviser Fouzul details that BTCL possesses a fibre network stretching over 39,500 km, 90 percent of which is underground.

BCC, on the other hand, has deployed 27,695 km of fibre under the InfoSarkar-3 project, which aims to expand high-speed internet access to rural areas covering 2,600 unions, with work ongoing for an additional 7,000 km expansion.

Meanwhile, PGCB has around 8,000 km of fibre along the power grid, a large portion of which remains unused. In addition, Bangladesh Railway owns 3,205 km of fibre lines, a significant part of which remains unused.

In his letter to the Ministry of Railways, Taiyeb states that leasing out the idle fibre networks could generate more than Tk 500 crore annually

Bringing fibre from the InfoSarkar-3 project, however, may not turn out to be that smooth, as the government inked a deal in 2023 with Summit Communications and Fibre@Home for maintenance, upgradation, replacement, and operation of the project.

The two private companies receive 90 percent of the revenue under the agreement. The ICT Division has recently sought to amend the deals.

Taiyeb, in the letter, said the lack of interconnectivity among these networks, combined with restrictive policies under the previous government, prevented entities like PGCB and Railway from offering last-mile connectivity to telecom operators—causing massive underutilisation of national assets.

The proposed national fibre bank aims to fix these issues by unifying the fibre networks of all four agencies into a single, centrally coordinated platform.

MORE REVENUE, FASTER INTERNET

In his letter to the Ministry of Railways, Taiyeb states that leasing out the idle fibre networks could generate more than Tk 500 crore annually.

Joint network maintenance under BTCL's experienced operations could reduce operating expenses by up to 30 percent.

Bandwidth cost from private NTTN operators is likely to fall from Tk 18,000 per Gbps to as low as Tk 5,000—a potential 70 percent reduction.

Besides, the letter states that only 25 percent of mobile towers are currently fibre-connected.

With an integrated backbone, this can reach 100 percent, allowing a low-cost, nationwide 5G rollout.

The overlapping paths of BTCL, PGCB, and Railway fibre also provide high redundancy, essential during natural disasters.

The initiative could enable 1 Gbps or higher internet speeds in every union by integrating existing Points of Presence (POPs) from BTCL (1,200 unions), BCC (2,600 unions), PGCB, and Railway.

The proposed national fibre bank would provide reliable, scalable access to telco-grade fibre—essential for services like IoT, telemedicine, distance education, and smart city development.

As per Taiyeb's letter, the proposed fibre bank will include a GIS-based real-time inventory system, identifying the location, core count, and status of each fibre line.

This will ensure transparency in leasing and allow selective, need-based access—for instance, during emergency government communications.

The letter also proposes an inter-ministerial meeting, involving Bangladesh Railway, PGCB, BTCL, BCC, and other stakeholders, to finalise the integration strategy and operational guidelines.

Companies that will lease fibre from the upcoming national fibre bank will be able to generate revenue from it. The earnings will be distributed among the government-owned companies, the telecom regulator, and the maintenance partners, Taiyeb said.

"For example, if Summit Communications and Fiber@Home are involved in maintenance, they will also receive a share of the revenue," he added.

LEVELLING THE PLAYING FIELD

In the letter, Taiyeb criticises the previous Awami League-led government for restricting state fibre owners from servicing telecom demand beyond their grid or track.

Such policies reportedly benefited certain politically connected private firms at the cost of public efficiency, the letter states.

The proposed fibre bank aims to level the playing field and put state-owned fibre assets to commercial and social use, within a regulatory framework that ensures transparency, competition, and affordability.

Fahim Mashroor, former president of the Bangladesh Association of Software and Information Services (BASIS), welcomed the move, saying it would benefit users by enabling faster and more affordable internet access.

"Particularly, if this initiative can ensure low-cost internet in remote areas, it will not only benefit consumers but also significantly boost Bangladesh's digital economy," he added.

The government has decided to establish a national "fibre optic bank", which will bring all unused fibre optic resources from state-owned entities under a single platform in a bid to accelerate digital transformation.

The telecom and ICT divisions have officially invited Bangladesh Railway and the Power Grid Company of Bangladesh (PGCB) to join this fibre-sharing consortium, alongside Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited (BTCL) and Bangladesh Computer Council (BCC).

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb, special assistant to the chief adviser with executive authority over the Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and Information Technology, recently sent a letter to Railways and Power Adviser Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan, outlining the government's vision for this initiative and urging participation.

40% OF PUBLIC FIBRE NETWORKS REMAIN UNUSED

The letter, seen by The Daily Star, states that over the past decade, different government agencies have installed thousands of kilometres of optical fibre—much of which remains underutilised or completely idle.

The letter notes that, in total, BTCL, PGCB, Railway, and BCC own 78,400 kilometres (km) of fibre network. Of this, an estimated 40 percent remains unused.

"We are wasting a vital national asset by leaving large portions of optical fibre unused. It's time we came together and built a centrally managed, transparent, and efficient fibre ecosystem for all," Taiyeb said.

He also said Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus has verbally endorsed the plan, enabling the Posts and Telecom Division to formally invite PGCB and Bangladesh Railway to the consortium.

"This is not just about connectivity. It's about bringing digital transformation where every union has high-speed access and every public resource is optimally used," he added.

Taiyeb's letter to Adviser Fouzul details that BTCL possesses a fibre network stretching over 39,500 km, 90 percent of which is underground.

BCC, on the other hand, has deployed 27,695 km of fibre under the InfoSarkar-3 project, which aims to expand high-speed internet access to rural areas covering 2,600 unions, with work ongoing for an additional 7,000 km expansion.

Meanwhile, PGCB has around 8,000 km of fibre along the power grid, a large portion of which remains unused. In addition, Bangladesh Railway owns 3,205 km of fibre lines, a significant part of which remains unused.

In his letter to the Ministry of Railways, Taiyeb states that leasing out the idle fibre networks could generate more than Tk 500 crore annually

Bringing fibre from the InfoSarkar-3 project, however, may not turn out to be that smooth, as the government inked a deal in 2023 with Summit Communications and Fibre@Home for maintenance, upgradation, replacement, and operation of the project.

The two private companies receive 90 percent of the revenue under the agreement. The ICT Division has recently sought to amend the deals.

Taiyeb, in the letter, said the lack of interconnectivity among these networks, combined with restrictive policies under the previous government, prevented entities like PGCB and Railway from offering last-mile connectivity to telecom operators—causing massive underutilisation of national assets.

The proposed national fibre bank aims to fix these issues by unifying the fibre networks of all four agencies into a single, centrally coordinated platform.

MORE REVENUE, FASTER INTERNET

In his letter to the Ministry of Railways, Taiyeb states that leasing out the idle fibre networks could generate more than Tk 500 crore annually.

Joint network maintenance under BTCL's experienced operations could reduce operating expenses by up to 30 percent.

Bandwidth cost from private NTTN operators is likely to fall from Tk 18,000 per Gbps to as low as Tk 5,000—a potential 70 percent reduction.

Besides, the letter states that only 25 percent of mobile towers are currently fibre-connected.

With an integrated backbone, this can reach 100 percent, allowing a low-cost, nationwide 5G rollout.

The overlapping paths of BTCL, PGCB, and Railway fibre also provide high redundancy, essential during natural disasters.

The initiative could enable 1 Gbps or higher internet speeds in every union by integrating existing Points of Presence (POPs) from BTCL (1,200 unions), BCC (2,600 unions), PGCB, and Railway.

The proposed national fibre bank would provide reliable, scalable access to telco-grade fibre—essential for services like IoT, telemedicine, distance education, and smart city development.

As per Taiyeb's letter, the proposed fibre bank will include a GIS-based real-time inventory system, identifying the location, core count, and status of each fibre line.

This will ensure transparency in leasing and allow selective, need-based access—for instance, during emergency government communications.

The letter also proposes an inter-ministerial meeting, involving Bangladesh Railway, PGCB, BTCL, BCC, and other stakeholders, to finalise the integration strategy and operational guidelines.

Companies that will lease fibre from the upcoming national fibre bank will be able to generate revenue from it. The earnings will be distributed among the government-owned companies, the telecom regulator, and the maintenance partners, Taiyeb said.

"For example, if Summit Communications and Fiber@Home are involved in maintenance, they will also receive a share of the revenue," he added.

LEVELLING THE PLAYING FIELD

In the letter, Taiyeb criticises the previous Awami League-led government for restricting state fibre owners from servicing telecom demand beyond their grid or track.

Such policies reportedly benefited certain politically connected private firms at the cost of public efficiency, the letter states.

The proposed fibre bank aims to level the playing field and put state-owned fibre assets to commercial and social use, within a regulatory framework that ensures transparency, competition, and affordability.

Fahim Mashroor, former president of the Bangladesh Association of Software and Information Services (BASIS), welcomed the move, saying it would benefit users by enabling faster and more affordable internet access.

"Particularly, if this initiative can ensure low-cost internet in remote areas, it will not only benefit consumers but also significantly boost Bangladesh's digital economy," he added.