Choices matter more than promises

Fixing public finances, repairing the financial sector top priorities

Selim Raihan

Published :

Feb 11, 2026 23:36

Updated :

Feb 11, 2026 23:36

A bank teller counting notes at a bank in Dhaka. Fixing the problems of the banking sector through long-term reform will be critical for the new government —FE File Photo

This article outlines a proactive policy agenda that goes beyond crisis control to promote purposeful growth. It emphasises the need for a more balanced macroeconomic strategy that controls inflation without choking investment, alongside realistic exchange rate management and stronger market governance. Reviving investment requires restoring predictability, improving law and order, and redesigning industrial policy to reward performance, diversification, and regional production ecosystems. The first part of the article, published on Wednesday (February 11), discussed the above mentioned areas. The current or last part analysis highlights domestic resource mobilisation, financial sector, trade competitiveness, employments and climate issues.

FIXING PUBLIC FINANCES – REVENUE MOBILISATION AS A DEVELOPMENT IMPERATIVE: Few issues are as central to Bangladesh’s economic future as public finance. The tax-to-GDP ratio is among the lowest globally, leaving the state with dangerously limited fiscal space. At the same time, fixed expenditures such as salaries, pensions, and interest payments consume a large share of revenue, crowding out spending on development and social services.

The result is visible. Public investment has been compressed. Spending on education, health, water, and social protection remains far below what is needed for inclusive growth. The state is asked to do more every year, but its revenue capacity remains weak. This is not sustainable.

Why revenue reform is about trust, not only enforcement. Domestic resource mobilisation must be at the heart of the next government’s economic strategy. But this is not simply about raising taxes. It is about building a fair, predictable, and credible revenue system that citizens and businesses can trust.

Broadening the tax base is essential. Too much of the burden falls on a narrow segment of formal firms, while many high-income individuals and large informal businesses remain outside the net. Reducing discretionary exemptions, simplifying laws, and digitising filing and payment systems can improve compliance while lowering harassment and arbitrariness.

Predictability matters as much as enforcement. When rules are clear and consistently applied, voluntary compliance improves. When enforcement is selective, negotiation-based, or punitive, evasion becomes rational.

Reforming tax administration: reducing arbitrariness and harassment. Institutional reform of tax administration is critical. Businesses often complain not only about rates but also about the uncertainty, the discretionary power of officials, and the transaction costs involved in compliance. When compliance feels like bargaining, the system becomes unfair and inefficient. The reform of the tax administration needs to be effective and stable.

Digitisation can reduce discretion, but only if it is paired with governance reforms: clear risk-based auditing, transparent procedures, stronger internal accountability, and better taxpayer services. A modern tax system should feel like a predictable contract, not like a negotiation every year.

Property taxation and local government finance. Property taxation is a largely untapped source of revenue, particularly in urban areas where land values have risen sharply. Properly designed, it can also improve urban planning and local service delivery. But property tax reform requires political courage, because it touches influential interests. Still, without stronger local revenue, urban services will continue to lag behind urban growth.

Subsidies, reprioritisation, and spending quality. Fiscal prudence must be accompanied by reprioritisation. Subsidies on energy, exports, and remittances, alongside inefficient transfers, need to be re-examined in the context of a more market-aligned exchange rate regime. Blanket subsidies distort incentives and often benefit those who need them least. Over time, targeted support is both cheaper and fairer.

Savings should be redirected to health, education, water, and targeted social protection. These are not “soft” sectors. They are productivity sectors. A healthier, better-educated workforce is the foundation of long-term growth.

Spending quality also matters. Too often, public investment focuses on visible infrastructure while neglecting maintenance, staffing, supervision, and accountability. The next government should shift from a project-count mentality to a results mentality. This includes improving procurement, reducing leakages, and strengthening monitoring.

Public investment as a catalyst, not a routine. Public investment has a role in stimulating economic activity and crowding in private investment, especially during periods of weak demand. But this is effective only when projects are well chosen and well implemented. Big initiatives should be grounded in evidence, with clear economic rationale, realistic timelines, and credible implementation frameworks. Otherwise, they become symbolic, expensive, and disappointing.

Repairing the Financial Sector — Restoring Trust and Credit Flow: A weak financial system cannot support a growth strategy. Bangladesh has lived with banking stress for years, but the crisis became more visible after 2024: distressed loans, weak governance, and battered public trust. Efficient firms struggled to access affordable credit, while well-connected borrowers defaulted without consequence. This distorted investment incentives and damaged the credibility of the entire system.

Banking reforms: progress, but still fragile. Bangladesh’s banking sector is now undergoing the most serious reform effort in decades, supported by international partners and grounded in the recognition that business as usual is no longer viable. Reinforcing the legal and regulatory framework to resolve ailing banks has been a cornerstone. Resolution mechanisms have expanded the central bank’s ability to intervene early, appoint administrators, and pursue orderly restructuring. Deposit protection has also been strengthened to stabilise confidence and reduce panic risk.

Supervision is being overhauled through asset quality reviews and a shift toward risk-based supervision. Governance reforms, including changes in some bank boards, aim to reduce political pressure and improve accountability.

These reforms are meaningful. But they remain fragile. Entrenched non-performing loans, pressure on regulatory independence, and resistance within the system continue to pose risks. Much depends on whether interference in regulatory decisions can be credibly reduced and whether reforms are sustained beyond the immediate crisis moment.

Non-performing loans: enforcement, transparency, and consequences. Non-performing loans remain the hardest issue. Tightened definitions and stricter rules against cosmetic rescheduling are necessary to improve transparency. But transparency alone does not recover money. Recovery requires enforcement, stronger legal processes, and coordination across institutions. Without consequences for wilful default, bad behaviour persists, and honest borrowers pay the price through higher interest rates.

A key principle should guide policy: resolution mechanisms must protect depositors, not shareholders who benefited from misgovernance. If the costs of failure are repeatedly socialised while gains are privatised, the system will never become disciplined.

Interest rates and the investment squeeze. High interest rates are not only a monetary policy issue. They reflect banking sector risk, NPL burdens, and weak competition. If inflation remains high and NPLs keep rising, rates stay elevated. This can create a vicious cycle: high rates weaken firms, defaults rise, banks become weaker, and rates remain high.

Breaking this cycle requires banking reform and inflation control together. It also requires better credit allocation, so productive firms are not crowded out by connected borrowers.

SMEs and credit access: targeted instruments, better governance. The financial crunch hits SMEs hardest. They often have viable businesses but limited collateral, weak documentation, and low bargaining power. Without credit, they cannot invest, hire, or upgrade technology.

The next government should expand well-governed development finance instruments: credit guarantees, refinancing windows tied to performance, and digital credit assessment tools that reduce reliance on connections. But governance is the core. If these instruments become new channels for rent seeking, they will fail.

Capital markets and long-term finance. Bangladesh’s capital market remains underdeveloped and suffers from low investor trust, partly due to governance weaknesses. Yet long-term finance is essential for infrastructure, green investment, innovation, and SME scaling. A stronger bond market, including SME oriented bond instruments, could mobilise savings into productive investment. But this requires better regulation, transparency, and enforcement to rebuild trust.

A diversified financial system, where firms can access both bank credit and market-based finance, is more resilient. Bangladesh needs that resilience.

Employment, Skills, and the Youth Challenge: Bangladesh’s demographic profile is both an opportunity and a risk. A large working-age population can power growth, but only if jobs are created at scale and skills keep pace with economic change.

The labour market today tells a troubling story. Employment growth has slowed. Underemployment is widespread. Educated youth face bleak prospects, feeding frustration and social tension. Informality remains the norm, limiting security and productivity. A large share of workers operate outside effective labour protections and outside stable career paths.

Employment as an explicit policy objective. The next government must put employment at the centre of economic policy, not as a by-product of growth but as an explicit objective. This means prioritising labour-intensive sectors, supporting micro and small enterprises, and ensuring that public investment choices also consider job creation.

Industrial policy should be evaluated not only by export earnings but also by employment intensity and skill upgrading potential. If growth becomes increasingly jobless, social tension rises, and political stability weakens. That feedback loop is real.

Skills: the binding constraint. Training systems remain a glaring weakness. Very few workers receive formal training. This is not a minor gap. It is a structural failure. Fixing it requires partnerships between government, industry, and training providers, with curricula aligned to labour market demand and global trends.

Curriculum reform is essential. Too often, education produces credentials rather than capabilities. Quality matters more than expansion alone. The government should support competency-based training, stronger apprenticeship programs, and industry-linked certification.

Financing human capital: skills loans and mobility support. One overlooked area is financing for skills development and labour mobility. Banks rarely lend for education, training, or overseas employment preparation. Yet these investments can yield high returns through higher wages and remittances.

A structured system of education and skills loans, combined with better safeguards and repayment mechanisms, can expand opportunities. It can also reduce inequality, because access to training should not depend only on family wealth.

Overseas employment: moving from volume to value.

Overseas migration remains a crucial employment channel. But the goal should shift from exporting low-skilled labour to exporting skilled labour. That requires better pre-departure training, lower migration costs, and stronger regulation of intermediaries who exploit workers.

Higher skills translate into higher wages abroad. They also translate into more stable remittance inflows. In a period where external demand is uncertain, skilled migration becomes a form of resilience.

Youth engagement and social stability. Youth engagement must go beyond employment alone. Young people want dignity, voice, and fairness. Platforms for participation, service, and civic engagement can channel energy into constructive pathways. Ignoring youth aspirations carries economic risks because social tension disrupts investment and weakens productivity.

Social Protection and Inequality – Investing in Resilience: Economic growth that bypasses large sections of society cannot be sustained. In Bangladesh, the weaknesses of the social protection system are no longer marginal. They are a central economic constraint. Programs remain fragmented, funding is inadequate, coordination is weak, and coverage is uneven. Urban vulnerability is rising quickly, yet many safety nets are still rural in design. When shocks hit, households fall through cracks, amplifying poverty and insecurity.

Social protection as economic infrastructure. The next government should treat social protection as an economic investment, not a residual welfare obligation. The aim should be coherence: programs organised around a lifecycle framework, predictable support for children, working-age people facing shocks, persons with disabilities, and older people.

Better targeting is vital, but targeting must be credible and updated. Integrated household data systems, frequently refreshed, can reduce exclusion and leakage. Yet inclusion must remain a guiding principle. If digital delivery systems are used, they must be accessible to those with low digital literacy, and safeguards must prevent arbitrary exclusion.

Urban food security and inflation resilience. Urban food security deserves special attention. Rising food prices, irregular incomes, and high housing costs have made many urban households vulnerable even when they sit above official poverty lines. Bringing them into targeted food distribution or cash support mechanisms can stabilise consumption and reduce distress. In periods of inflation, such measures also support macro stability by dampening panic and protecting demand.

Inequality in public services. Tackling inequality also hinges on access to good-quality public services. Education and health outcomes are shaped not only by budget allocations but by planning failures, staffing gaps, and weak accountability. Too often, spending favourson buildings and equipment rather than teachers, health workers, supervision, and performance systems.

A stronger social protection system must therefore be accompanied by sustained investment in education and health systems. Households that feel protected from shocks and have access to dependable services are more likely to invest in skills, take productive risks, and participate in the economy. That is how resilience supports growth.

Trade, LDC Graduation, and Global Positioning: As Bangladesh approaches Least Developed Country (LDC) graduation in November 2026, trade policy is no longer a technical afterthought. It is becoming a central arena where the future growth path will be determined. Graduation is an achievement, but it removes a protective layer that supported export success for decades. Preferential access will fade. Compliance demands will tighten. Competition will become sharper, often in ways that are not immediately visible but deeply consequential.

Competing without cushions: the new discipline. Bangladesh must learn to compete without special treatment, without losing jobs or export earnings during the transition. That requires moving away from a trade regime built on preferences and protection, toward one built on competitiveness, predictability, and integration.

Exports remain heavily concentrated. Preferential access has masked weaknesses in logistics, customs, standards, and trade facilitation. Graduation will slowly remove that cushion. Exports may not collapse overnight, but the margin for error will narrow sharply. Delays at ports, erratic customs practices, abrupt tariff changes, or weak enforcement of standards will increasingly translate into lost contracts.

Competitiveness is system-wide. Exchange rate policy matters, but so do speed, reliability, standards infrastructure, and firm capabilities. In a post LDC environment, success depends not only on price but on consistency and the ability to upgrade.

Reducing anti-export bias: tariff rationalisation and input costs. A central weakness in Bangladesh’s trade regime is a strong anti-export bias. High tariffs and para-tariffs push firms toward protected domestic markets. As preferences erode, this structure becomes costly. Exporters face higher input prices and weaker incentives to diversify.

The next government should pursue phased tariff rationalisation. The objective is not sudden liberalisation, but simpler, more transparent systems that allow exporters to access inputs at world prices. Policy stability is essential. Frequent discretionary changes discourage investment and undermine confidence.

Trade facilitation: where competitiveness is won or lost. For many exporters, domestic inefficiencies matter more than foreign tariffs. Port congestion, slow clearance, poor coordination among border agencies, and excessive documentation create uncertainty. In modern supply chains, even small delays can shift orders elsewhere.

Measures such as single window systems, risk-based controls, electronic documentation, and better logistics connectivity can produce large competitiveness gains. These reforms are less glamorous than mega projects, but they often deliver higher returns.

Diversification through value chain deepening. Diversification does not mean abandoning garments. It means broadening the export base and deepening domestic value chains. Backward linkages deserve priority to reduce import dependence, improve resilience, and raise domestic value addition. Sector support should be focused on a limited set of promising areas and linked to performance, not entitlements.

Global economic strategy: pragmatic partnerships. Bangladesh’s global positioning must be pragmatic. Trade and investment partnerships should be diversified across regions. The aim is not to choose sides, but to secure markets, technology, investment, and energy sources while protecting national interests. In a more fragmented global economy, diversification of partnerships becomes a risk management strategy.

Climate, Rural Development, and Long-term Sustainability: Climate vulnerability is not a distant prospect. It is shaping livelihoods, migration, and public spending now. The next government must embed climate adaptation and mitigation into mainstream economic planning, not treat them as separate projects.

Energy security: the overlooked growth constraint. Energy insecurity has become a serious constraint. When power supply is unreliable, and fuel costs are high, production becomes uncertain, and inflation pressures rise. A credible energy strategy must balance short-term supply needs with long term transition goals.

This means improving procurement and planning for imported fuels while accelerating the shift toward renewables. Solar expansion has real potential, especially where land can be utilised creatively. But renewables need grid upgrades, storage planning, and regulatory clarity. Without these, targets remain paper goals.

Energy pricing reform also matters. Blanket subsidies distort incentives and drain fiscal space. Moving toward targeted support for vulnerable consumers and strategic sectors, while allowing more market-consistent pricing, can reduce distortions and improve investment signals.

Rural development: livelihoods, services, and climate resilience. Rural development deserves renewed focus. Growth driven purely by mega projects and urban sprawl will not solve waterlogging, rural unemployment, or climate stress. Local development models that integrate infrastructure, livelihoods, services, and environmental management can produce more balanced outcomes.

Climate-resilient agriculture, better water management, and rural non-farm employment are crucial. They reduce distress migration and strengthen food security. They also support political stability by ensuring rural regions do not feel left behind.

Green opportunities: jobs and competitiveness. Green investment is not only an environmental priority. It is an economic opportunity. Renewable energy components, energy-efficient manufacturing, climate-resilient infrastructure, and green financing can generate jobs and attract investment, especially as global buyers increasingly demand low-carbon production.

Embedding sustainability into industrial policy can therefore strengthen competitiveness in a post-LDC world, where compliance and environmental standards will matter more.

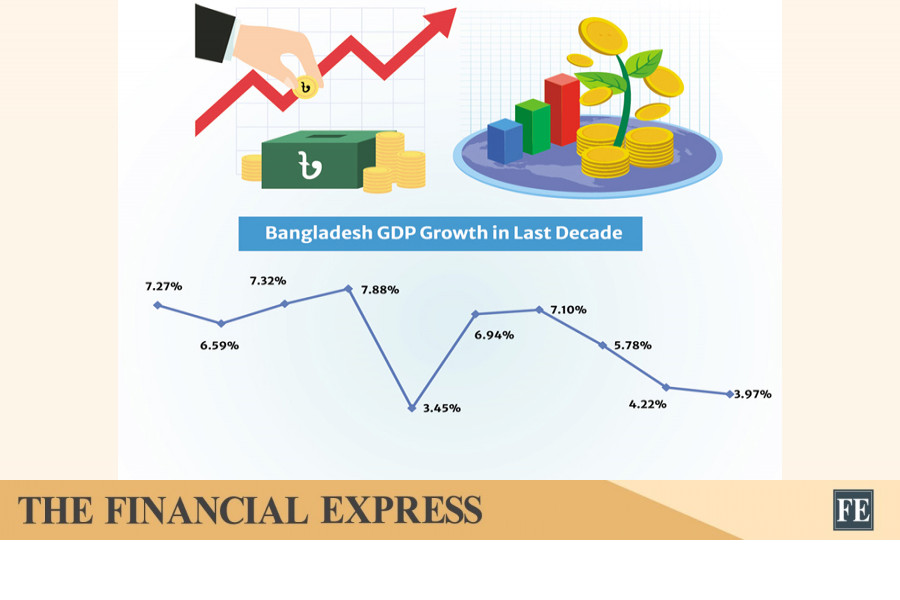

Conclusion — Choosing Direction, not Drifting: The next government will inherit an economy that appears to be more stable than it was two years ago, but also more fragile in its foundations. Stabilisation has bought time. It has not solved deeper problems: weak investment, limited job creation, fiscal stress, banking fragility, and inequality.

The priorities outlined here point to a clear direction. Restore confidence through predictability and the rule of law. Broaden the production base through disciplined industrial policy and regional ecosystems. Mobilise domestic resources through fair, credible tax reform and better spending quality. Repair the financial system in a way that restores trust and reopens credit flow for productive firms. Put jobs, skills, and youth aspirations at the centre of policy. Strengthen social protection as resilience infrastructure. Prepare seriously for a post-LDC trade regime by improving competitiveness, reducing anti-export bias, and investing in trade facilitation. And embed climate resilience and energy security into the core of development planning.

None of this will be easy. Vested interests will resist. Administrative inertia will slow progress. Mistakes will happen. But the alternative, drifting back into business as usual, carries greater risks. It risks locking the country into a low-growth equilibrium where inflation remains painful, investment remains hesitant, and opportunities remain scarce.

Bangladesh has reached a moment where choices matter more than promises. If the next government can act with clarity, discipline, and inclusiveness, it can move beyond crisis management and build purposeful growth that creates jobs and widens opportunity. If it cannot, the cost will not only show up in indicators. It will show up in the everyday lives of millions whose aspirations remain unmet.

[Concluded]

Dr Selim Raihan is a Professor at the Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, and Executive Director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM).