Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,949

- Likes

- 8,155

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Playing the victim while sitting on loot

Bangladesh's push to recover stolen assets has entered a much trickier and consequential stage with business tycoon Mohammad Saiful Alam dragging the country to international arbitration under the Bangladesh-Singapore bilateral investment treaty. Having acquired Singaporean citizenship only in rece

Playing the victim while sitting on loot

SYED MUHAMMED SHOWAIB

Published :

Jan 30, 2026 23:54

Updated :

Jan 30, 2026 23:54

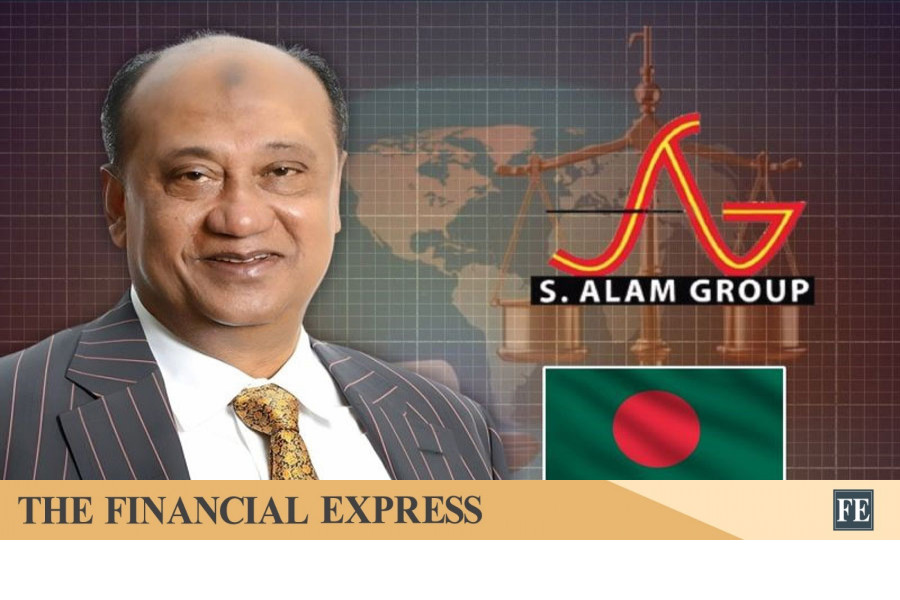

Bangladesh's push to recover stolen assets has entered a much trickier and consequential stage with business tycoon Mohammad Saiful Alam dragging the country to international arbitration under the Bangladesh-Singapore bilateral investment treaty. Having acquired Singaporean citizenship only in recent years after renouncing their Bangladeshi nationality, Alam, his wife Farzana Parveen, and sons Ashraful Alam and Asadul Alam Mahir are now casting themselves as foreign investors wronged by their former homeland. Represented by the elite firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, they seek not merely to shield vast assets but to hit Bangladesh with a massive claim for damages and costs by taking advantage of the treaty meant to encourage legitimate investment.

This legal offensive follows what is widely considered the most devastating act of financial crime in the nation's history. During the latter years of the fallen Awami League government, companies linked to the S Alam Group, with support from within the administration, seized control of nearly all Shariah-based banks by circumventing the Banking Companies Act of 1991. After consolidating power, they forced out senior management and existing boards, replaced them with loyalists and extracted trillions of taka through fraudulent loans that were later funnelled abroad. Subjecting private banks to such a methodical and carefully orchestrated loan fraud on a scale possibly unseen anywhere else, let alone in a developing nation like Bangladesh, has only magnified the damage many times over.

Arguably, this ruination of financial sector through the activities of S Alam and similar groups was a primary source of public loathing towards the previous government, a sentiment that helped lay the groundwork for the July uprising. Upon assuming office, the interim government declared the recovery of laundered assets a top priority. Eleven inter agency taskforces were formed to track down the trillions believed to have been laundered abroad by politically connected business groups. Expectations were understandably high. Yet, as the government's term comes to the end, the performance of these task forces has been largely underwhelming. This shortfall is attributed to a confluence of factors, ranging from the absence of a central reporting authority and poor inter-agency coordination to unclear mandates, budgetary constraints and limited specialised expertise. Parallel efforts to engage foreign legal firms have likewise yielded little visible progress, also hampered by budgetary constraints and the absence of a standard methodology.

While domestic agencies struggled to act in concert, Saiful Alam, the man who benefited most from the banking plunder, moved decisively on the international stage. In a move that resembles a thief sounding the alarm, he along with his wife and two sons Ashraful Alam and Asadul Alam Mahir, initiated arbitration proceedings against Bangladesh at the World Bank-affiliated ICSID invoking the Bangladesh-Singapore Bilateral Investment Treaty. Their apparent objective is to entangle the state in protracted arbitration to shield their overseas assets and potentially claim hundreds of millions in damages. Bilateral investment treaties are agreements between states designed to protect foreign investors and encourage capital inflows. In 2004, Bangladesh signed one with Singapore in the hopes of attracting investment.

The family's claim of Singaporean nationality is central to the case, as the arbitration body only hears disputes between a state and nationals of another state. As purported Singaporean investors, they allege that Bangladesh breached its obligations under the treaty with respect to their investments. However, by their own admission, Saiful Alam, Farzana Parveen and Asadul Alam Mahir became Singaporean citizens on 12 September 2023 while Ashraful Alam acquired citizenship on 29 July 2021. All four had renounced their Bangladeshi nationality on August 3, 2020.

While the claimants may have held Singaporean passports at the time they filed for arbitration, the investments in question were neither made when they were Singaporean nationals nor financed with income lawfully earned in Singapore. An investigative report published in The Daily Star on 4 August 2023, prior to their change in nationality, titled S Alam's Aladdin's lamp, detailed how Saiful Alam built a business empire in Singapore worth at least one billion dollars, including hotels and real estate without approval from Bangladesh Bank to transfer funds or invest abroad. The central question for arbitration, therefore, must be whether treaty protections extend to assets acquired with funds illicitly expatriated before the claimants became foreign citizens. To hold otherwise would be to allow a party to seek international arbitration for the protection of assets stolen from the very country they are now suing.

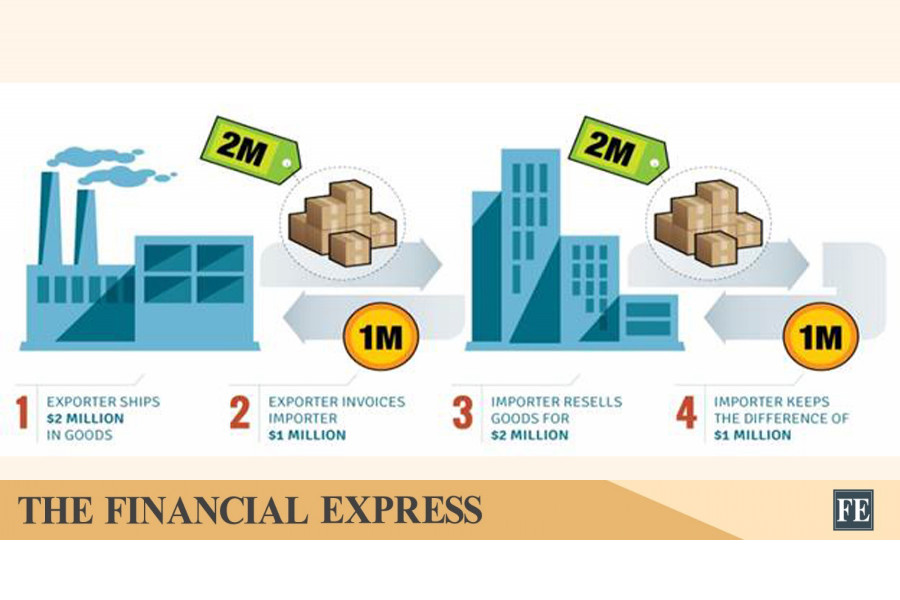

Saiful Alam and his cronies drained several Shariah-based banks to such an extent that many devout Muslims now fear using them. Companies linked to him also misappropriated loans from conventional banks including the state-owned Janata Bank. Loans were taken both in the names of his own companies and through others including many unwitting individuals in whose names accounts had been opened. Portions of these funds fuelled domestic operations, while the bulk flowed overseas, laundered through layered ownership structures involving proxies and shell companies to obscure the family's trail. One investigator likened the trail to footprints that suddenly vanish, leaving trackers guessing where they lead. Even attempts by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) to recover some of the remaining liquid assets through tax demands reportedly faced resistance from Islami Bank, demonstrating the significant institutional and political hurdles in the recovery process.

Now that Saiful Alam has sought redress through international arbitration, Bangladesh has little choice but to contest the case. The matter must be treated with utmost seriousness, particularly given precedents where countries such as Argentina have lost arbitration cases and been ordered to pay substantial sums. Bangladesh's strategy must rest on clearly and factually showing that the assets in question belonged to the country were acquired through illicit means before the claimants assumed Singaporean citizenships, and that their later change of nationality does not legitimise the theft or entitle them to the protections of a treaty meant for genuine foreign investors.

SYED MUHAMMED SHOWAIB

Published :

Jan 30, 2026 23:54

Updated :

Jan 30, 2026 23:54

Bangladesh's push to recover stolen assets has entered a much trickier and consequential stage with business tycoon Mohammad Saiful Alam dragging the country to international arbitration under the Bangladesh-Singapore bilateral investment treaty. Having acquired Singaporean citizenship only in recent years after renouncing their Bangladeshi nationality, Alam, his wife Farzana Parveen, and sons Ashraful Alam and Asadul Alam Mahir are now casting themselves as foreign investors wronged by their former homeland. Represented by the elite firm Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, they seek not merely to shield vast assets but to hit Bangladesh with a massive claim for damages and costs by taking advantage of the treaty meant to encourage legitimate investment.

This legal offensive follows what is widely considered the most devastating act of financial crime in the nation's history. During the latter years of the fallen Awami League government, companies linked to the S Alam Group, with support from within the administration, seized control of nearly all Shariah-based banks by circumventing the Banking Companies Act of 1991. After consolidating power, they forced out senior management and existing boards, replaced them with loyalists and extracted trillions of taka through fraudulent loans that were later funnelled abroad. Subjecting private banks to such a methodical and carefully orchestrated loan fraud on a scale possibly unseen anywhere else, let alone in a developing nation like Bangladesh, has only magnified the damage many times over.

Arguably, this ruination of financial sector through the activities of S Alam and similar groups was a primary source of public loathing towards the previous government, a sentiment that helped lay the groundwork for the July uprising. Upon assuming office, the interim government declared the recovery of laundered assets a top priority. Eleven inter agency taskforces were formed to track down the trillions believed to have been laundered abroad by politically connected business groups. Expectations were understandably high. Yet, as the government's term comes to the end, the performance of these task forces has been largely underwhelming. This shortfall is attributed to a confluence of factors, ranging from the absence of a central reporting authority and poor inter-agency coordination to unclear mandates, budgetary constraints and limited specialised expertise. Parallel efforts to engage foreign legal firms have likewise yielded little visible progress, also hampered by budgetary constraints and the absence of a standard methodology.

While domestic agencies struggled to act in concert, Saiful Alam, the man who benefited most from the banking plunder, moved decisively on the international stage. In a move that resembles a thief sounding the alarm, he along with his wife and two sons Ashraful Alam and Asadul Alam Mahir, initiated arbitration proceedings against Bangladesh at the World Bank-affiliated ICSID invoking the Bangladesh-Singapore Bilateral Investment Treaty. Their apparent objective is to entangle the state in protracted arbitration to shield their overseas assets and potentially claim hundreds of millions in damages. Bilateral investment treaties are agreements between states designed to protect foreign investors and encourage capital inflows. In 2004, Bangladesh signed one with Singapore in the hopes of attracting investment.

The family's claim of Singaporean nationality is central to the case, as the arbitration body only hears disputes between a state and nationals of another state. As purported Singaporean investors, they allege that Bangladesh breached its obligations under the treaty with respect to their investments. However, by their own admission, Saiful Alam, Farzana Parveen and Asadul Alam Mahir became Singaporean citizens on 12 September 2023 while Ashraful Alam acquired citizenship on 29 July 2021. All four had renounced their Bangladeshi nationality on August 3, 2020.

While the claimants may have held Singaporean passports at the time they filed for arbitration, the investments in question were neither made when they were Singaporean nationals nor financed with income lawfully earned in Singapore. An investigative report published in The Daily Star on 4 August 2023, prior to their change in nationality, titled S Alam's Aladdin's lamp, detailed how Saiful Alam built a business empire in Singapore worth at least one billion dollars, including hotels and real estate without approval from Bangladesh Bank to transfer funds or invest abroad. The central question for arbitration, therefore, must be whether treaty protections extend to assets acquired with funds illicitly expatriated before the claimants became foreign citizens. To hold otherwise would be to allow a party to seek international arbitration for the protection of assets stolen from the very country they are now suing.

Saiful Alam and his cronies drained several Shariah-based banks to such an extent that many devout Muslims now fear using them. Companies linked to him also misappropriated loans from conventional banks including the state-owned Janata Bank. Loans were taken both in the names of his own companies and through others including many unwitting individuals in whose names accounts had been opened. Portions of these funds fuelled domestic operations, while the bulk flowed overseas, laundered through layered ownership structures involving proxies and shell companies to obscure the family's trail. One investigator likened the trail to footprints that suddenly vanish, leaving trackers guessing where they lead. Even attempts by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) to recover some of the remaining liquid assets through tax demands reportedly faced resistance from Islami Bank, demonstrating the significant institutional and political hurdles in the recovery process.

Now that Saiful Alam has sought redress through international arbitration, Bangladesh has little choice but to contest the case. The matter must be treated with utmost seriousness, particularly given precedents where countries such as Argentina have lost arbitration cases and been ordered to pay substantial sums. Bangladesh's strategy must rest on clearly and factually showing that the assets in question belonged to the country were acquired through illicit means before the claimants assumed Singaporean citizenships, and that their later change of nationality does not legitimise the theft or entitle them to the protections of a treaty meant for genuine foreign investors.