Saif

Senior Member

- 13,786

- 7,411

- Origin

- Axis Group

Source

:

https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/editorial/news/protect-historic-sites-preserve-our-past-3640341

Protect historic sites, preserve our past

Mymensingh's Alexandra Castle should be renovated urgently

VISUAL: STAR

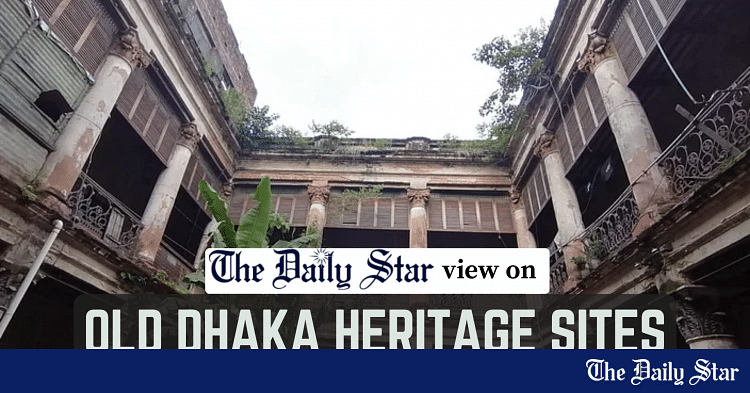

Bangladesh has a rich history and culture, but when it comes to preserving our heritage sites, we do a poor job. The Alexandra Castle in Mymensingh city is a glaring example of our apathy towards preservation work. A report in this daily details how this beautiful 145-year-old structure, built mostly with wood and iron, has fallen into ruins as a result.

Built as a guest house in 1879, the two-storey, tin-shade building once lodged dignitaries including Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. Since the Partition, it has been used by Teachers' Training College for various purposes. The first floor was used as a teachers' dormitory, which had to be moved later because of the floor's precarious condition. The ground floor has a library, but it is seldom used. That this beautiful architecture, popularly known as "Lohar Kuthi," has been in dire need of renovation for years is evident everywhere, from the plinth on which the building stands to the iron balusters, the louvered shutters on the balcony, the decorative balusters on the roof, and even the two partially broken Greek sculptures on the building premises.

According to the Department of Archaeology (DoA), the kuthi was enlisted as an archaeological site in 2018. It is obvious that the department did not carry out any renovation on the building in the last six years. A top official told our district correspondent that necessary funds for renovation and restoration of all archaeological sites in Dhaka and Mymensingh divisions have been approved, and that the work will start in the next fiscal year, meaning sometime between July 2024 and June 2025.

Such a statement should make us hopeful, but it is difficult to take DoA at its word. The department's past performance in terms of protecting, preserving and restoring heritage sites has been quite disappointing. It has 113 archaeological sites under its protection, but the conditions of many of those remain far from protected, with many facing threats of ruin and illegal occupation. We urge the DoA to push aside its lacklustre attitude and realise its mandate to restore and preserve these historical landmarks, keeping their architectural integrity intact.

Mymensingh's Alexandra Castle should be renovated urgently

VISUAL: STAR

Bangladesh has a rich history and culture, but when it comes to preserving our heritage sites, we do a poor job. The Alexandra Castle in Mymensingh city is a glaring example of our apathy towards preservation work. A report in this daily details how this beautiful 145-year-old structure, built mostly with wood and iron, has fallen into ruins as a result.

Built as a guest house in 1879, the two-storey, tin-shade building once lodged dignitaries including Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. Since the Partition, it has been used by Teachers' Training College for various purposes. The first floor was used as a teachers' dormitory, which had to be moved later because of the floor's precarious condition. The ground floor has a library, but it is seldom used. That this beautiful architecture, popularly known as "Lohar Kuthi," has been in dire need of renovation for years is evident everywhere, from the plinth on which the building stands to the iron balusters, the louvered shutters on the balcony, the decorative balusters on the roof, and even the two partially broken Greek sculptures on the building premises.

According to the Department of Archaeology (DoA), the kuthi was enlisted as an archaeological site in 2018. It is obvious that the department did not carry out any renovation on the building in the last six years. A top official told our district correspondent that necessary funds for renovation and restoration of all archaeological sites in Dhaka and Mymensingh divisions have been approved, and that the work will start in the next fiscal year, meaning sometime between July 2024 and June 2025.

Such a statement should make us hopeful, but it is difficult to take DoA at its word. The department's past performance in terms of protecting, preserving and restoring heritage sites has been quite disappointing. It has 113 archaeological sites under its protection, but the conditions of many of those remain far from protected, with many facing threats of ruin and illegal occupation. We urge the DoA to push aside its lacklustre attitude and realise its mandate to restore and preserve these historical landmarks, keeping their architectural integrity intact.