Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,262

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Dhaka hospitals need urgent support

They are struggling to provide necessary care to patients

Dhaka hospitals need urgent support

They are struggling to provide optimal care to patients

VISUAL: STAR

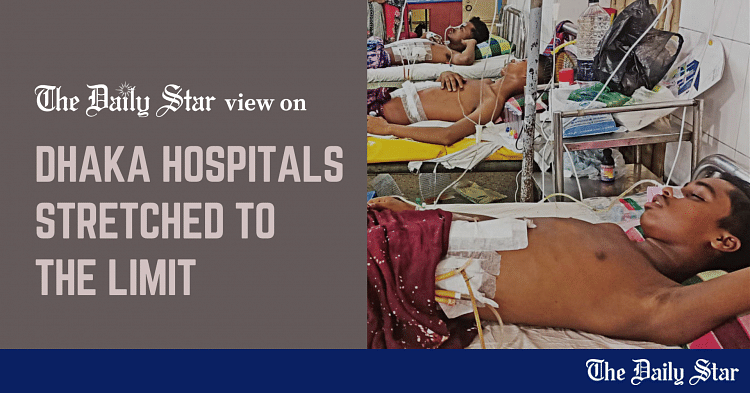

The updates coming from several government hospitals in Dhaka in the aftermath of recent violent clashes are quite concerning. These hospitals, treating people injured during the unrest centring the quota reform movement, are struggling to provide optimal care due to the sheer number of incoming patients, as per a report in this daily. Clearly, these and other public hospitals in major cities need proper support from the authorities.

According to our report, the hospitals in Dhaka, especially the Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), have been stretched thin since July 18, when violent attacks spread out across the city. People were injured with shotgun bullets or pellets as police and Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) troops shot at protesters and alleged infiltrators. At the DMCH, some 1,071 people wounded by sharp weapons, bullets and/or pellets sought treatment between July 15 and 22. Most of these victims—ranging from teenagers to middle-aged individuals—said they were merely bystanders or commuters and not associated with the protests or clashes. All the patients currently admitted at the DMCH were injured critically and had to undergo surgery. Overwhelmed by the surge, the hospital had to prematurely discharge those who had come in before the start of the violence to make room. The situation is similar at Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital (SSMCH), NITOR, and the National Institute of Ophthalmology.

Healthcare services in general have been facing a massive disruption due to the ongoing situation. Due to the nationwide internet shutdown, which came into effect on July 18 night, private medical colleges, hospitals and diagnostic centres have been unable to provide services, according to another report in this daily. All online healthcare services have been out of reach as well. These facilities and services cater to a significantly large number of people in Bangladesh.

Given the unprecedented levels of violence, deaths and destruction seen over the past week, it is understandable that hospitals would get overwhelmed to some extent. However, as we have said numerous times before, an emergency service sector like healthcare must always have contingency plans anticipating all kinds of crisis. We urge the government to urgently mobilise all resources needed for the DMCH and other hospitals so that they can provide the best possible treatment to patients. The medical professionals who worked tirelessly in such a high-stress situation deserve some compensations as well.

The limited restoration of internet services is a positive turn of events; this means private healthcare facilities and online services can get back to doing their job. We expect the authorities to extend the necessary logistical and technical support to all healthcare service providers so they can help people without disruption.

They are struggling to provide optimal care to patients

VISUAL: STAR

The updates coming from several government hospitals in Dhaka in the aftermath of recent violent clashes are quite concerning. These hospitals, treating people injured during the unrest centring the quota reform movement, are struggling to provide optimal care due to the sheer number of incoming patients, as per a report in this daily. Clearly, these and other public hospitals in major cities need proper support from the authorities.

According to our report, the hospitals in Dhaka, especially the Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), have been stretched thin since July 18, when violent attacks spread out across the city. People were injured with shotgun bullets or pellets as police and Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) troops shot at protesters and alleged infiltrators. At the DMCH, some 1,071 people wounded by sharp weapons, bullets and/or pellets sought treatment between July 15 and 22. Most of these victims—ranging from teenagers to middle-aged individuals—said they were merely bystanders or commuters and not associated with the protests or clashes. All the patients currently admitted at the DMCH were injured critically and had to undergo surgery. Overwhelmed by the surge, the hospital had to prematurely discharge those who had come in before the start of the violence to make room. The situation is similar at Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College Hospital (SSMCH), NITOR, and the National Institute of Ophthalmology.

Healthcare services in general have been facing a massive disruption due to the ongoing situation. Due to the nationwide internet shutdown, which came into effect on July 18 night, private medical colleges, hospitals and diagnostic centres have been unable to provide services, according to another report in this daily. All online healthcare services have been out of reach as well. These facilities and services cater to a significantly large number of people in Bangladesh.

Given the unprecedented levels of violence, deaths and destruction seen over the past week, it is understandable that hospitals would get overwhelmed to some extent. However, as we have said numerous times before, an emergency service sector like healthcare must always have contingency plans anticipating all kinds of crisis. We urge the government to urgently mobilise all resources needed for the DMCH and other hospitals so that they can provide the best possible treatment to patients. The medical professionals who worked tirelessly in such a high-stress situation deserve some compensations as well.

The limited restoration of internet services is a positive turn of events; this means private healthcare facilities and online services can get back to doing their job. We expect the authorities to extend the necessary logistical and technical support to all healthcare service providers so they can help people without disruption.