Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 17,503

- Likes

- 8,438

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Reforms crucial for a functioning democracy

Govt must implement some key changes before election

Reforms crucial for a functioning democracy

Govt must implement some key changes before election

VISUAL: STAR

It is disheartening that the interim government has yet to take any major initiative to implement the proposed reforms by various reform commissions. The July uprising created a rare political opening, raising public expectations that long-delayed institutional reforms would finally happen. Yet, many crucial proposals remain ignored, diluted, or quietly dropped, undermining the very purpose for which these commissions were formed. In this context, the frustration expressed by the chiefs and members of several reform commissions over the lack of implementation is justifiable.

Reportedly, a wide gap persists between recommendations and implementation, with many major reforms stalled and recommendations dropped. A telling example is the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) Reform Commission's proposal for quarterly public accountability reports. This recommendation was neither radical nor complex; it sought only to introduce basic transparency in a vital institution. Despite this being one of the commission's most important proposals, it was later removed. And despite broad political support for most other proposals, many were not enforced.

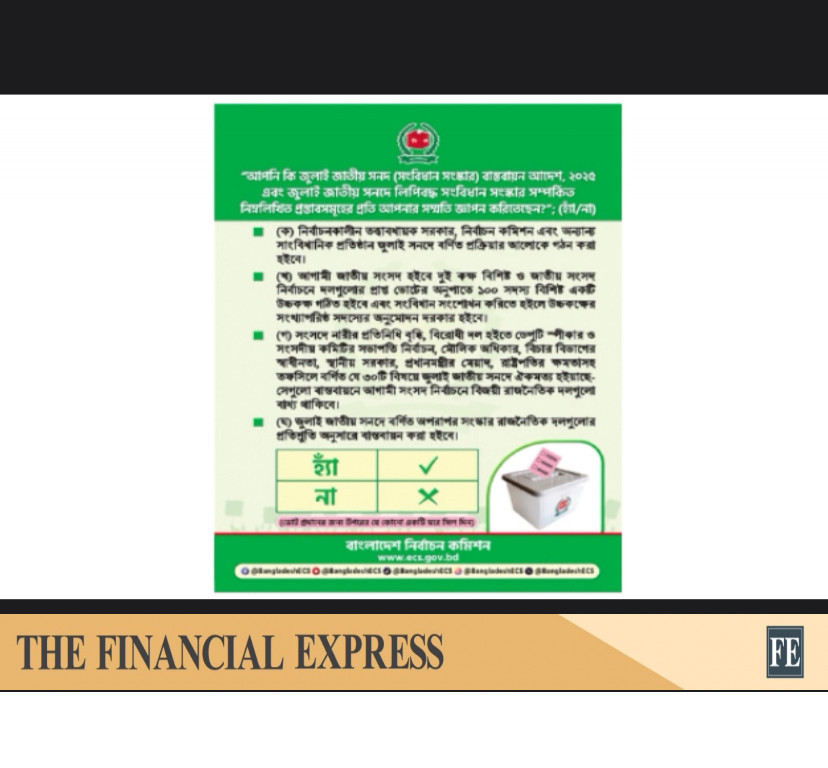

The Election Reform Commission's experience is equally disheartening. Its proposals to promote internal party democracy, ensure transparency in political financing, and strengthen candidate scrutiny were meant to address the root causes of the country's dysfunctional electoral culture. Key recommendations—such as electing party leaders from the grassroots, limiting the influence of wealthy individuals, and bringing parties under the Right to Information Act—were not adopted. While the Election Commission has taken some immediate steps, including better affidavit disclosure and expanded CCTV coverage, these fall short of tackling deeper problems like nomination syndromes, unchecked campaign spending, and weak accountability.

Perhaps most concerning is the state of media reforms. Reportedly, the Media Reform Commission proposed more than 100 reforms, yet not a single one has been implemented. Dropping the proposed Journalism Protection Act raises serious concerns about the safety of journalists, especially as the national election draws near. A free and secure media is central to any credible democratic process. The government's rejection of a plan to establish a permanent, independent media commission is also unfortunate.

While reforms cannot be achieved overnight, many of the recommendations made by the commissions could have been implemented through routine administrative orders or minor legal adjustments. The problem, therefore, is less about capacity and more about commitment. Economists and civil society leaders have rightly warned that Bangladesh's democratic decline has been driven by an alliance of political, bureaucratic, and business interests resistant to change.

Without progress in implementation, reforms risk becoming yet another missed opportunity—one the country can ill afford as it seeks a credible return to democratic governance.

Govt must implement some key changes before election

VISUAL: STAR

It is disheartening that the interim government has yet to take any major initiative to implement the proposed reforms by various reform commissions. The July uprising created a rare political opening, raising public expectations that long-delayed institutional reforms would finally happen. Yet, many crucial proposals remain ignored, diluted, or quietly dropped, undermining the very purpose for which these commissions were formed. In this context, the frustration expressed by the chiefs and members of several reform commissions over the lack of implementation is justifiable.

Reportedly, a wide gap persists between recommendations and implementation, with many major reforms stalled and recommendations dropped. A telling example is the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) Reform Commission's proposal for quarterly public accountability reports. This recommendation was neither radical nor complex; it sought only to introduce basic transparency in a vital institution. Despite this being one of the commission's most important proposals, it was later removed. And despite broad political support for most other proposals, many were not enforced.

The Election Reform Commission's experience is equally disheartening. Its proposals to promote internal party democracy, ensure transparency in political financing, and strengthen candidate scrutiny were meant to address the root causes of the country's dysfunctional electoral culture. Key recommendations—such as electing party leaders from the grassroots, limiting the influence of wealthy individuals, and bringing parties under the Right to Information Act—were not adopted. While the Election Commission has taken some immediate steps, including better affidavit disclosure and expanded CCTV coverage, these fall short of tackling deeper problems like nomination syndromes, unchecked campaign spending, and weak accountability.

Perhaps most concerning is the state of media reforms. Reportedly, the Media Reform Commission proposed more than 100 reforms, yet not a single one has been implemented. Dropping the proposed Journalism Protection Act raises serious concerns about the safety of journalists, especially as the national election draws near. A free and secure media is central to any credible democratic process. The government's rejection of a plan to establish a permanent, independent media commission is also unfortunate.

While reforms cannot be achieved overnight, many of the recommendations made by the commissions could have been implemented through routine administrative orders or minor legal adjustments. The problem, therefore, is less about capacity and more about commitment. Economists and civil society leaders have rightly warned that Bangladesh's democratic decline has been driven by an alliance of political, bureaucratic, and business interests resistant to change.

Without progress in implementation, reforms risk becoming yet another missed opportunity—one the country can ill afford as it seeks a credible return to democratic governance.