Krishna with Flute

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 26, 2024

- Messages

- 5,369

- Likes

- 2,952

- Axis Group

Isha foundation planted 23 million trees in a single year. UN said that it is the biggest plantation drive of the world but sadguru said that it is not enough.

Here in Surat, lots of plantation happens. Government Nursery distributes lots of plants. An NGO with whom I am associated has planted 25000 trees this rainy season. I planted 4000+ trees this season.

Vanishing urban greenery

Bangladesh's capital Dhaka has been ranked among the world's fastest-growing cities, accommodating around 21 per cent of the country's total population. According to the UN's World Urbanization Prospects 2025 report, Dhaka has become the world's second most populous city, after Jakarta of Indonesiathefinancialexpress.com.bd

Vanishing urban greenery

Shiabur Rahman

Published :

Jan 08, 2026 23:20

Updated :

Jan 08, 2026 23:20

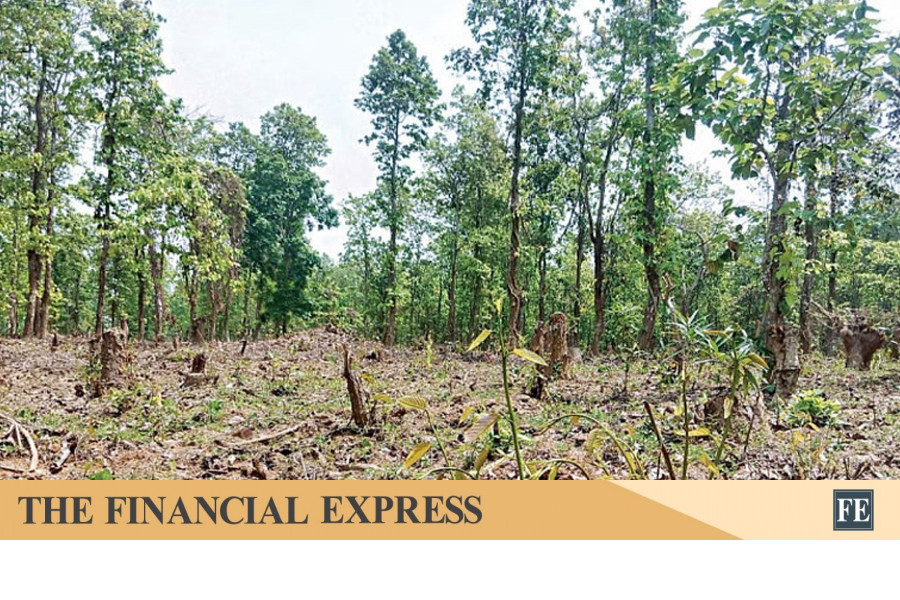

View attachment 23620

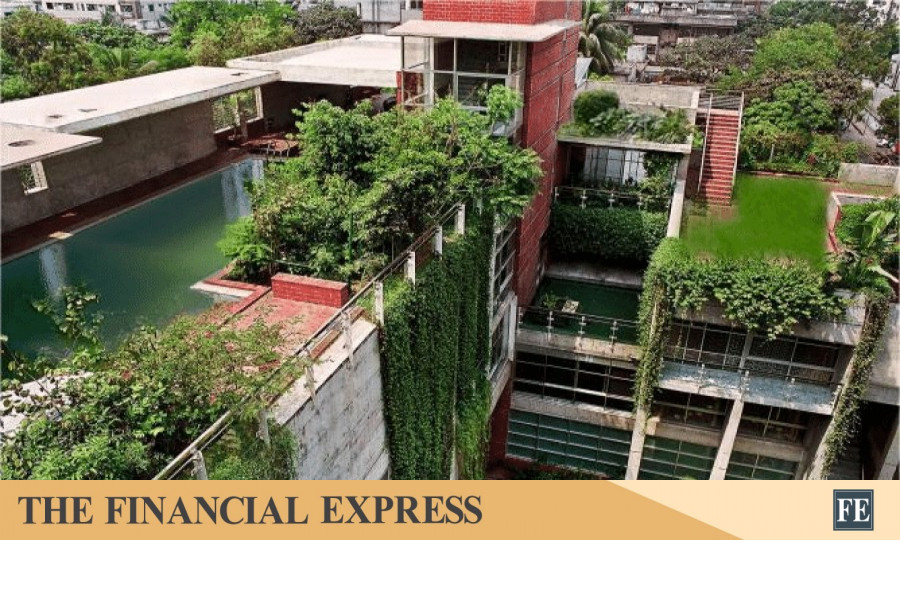

Bangladesh's capital Dhaka has been ranked among the world's fastest-growing cities, accommodating around 21 per cent of the country's total population. According to the UN's World Urbanization Prospects 2025 report, Dhaka has become the world's second most populous city, after Jakarta of Indonesia, with an estimated 36.6 million dwellers out of the country's total population of 175 million. To accommodate the ever-growing population, Dhaka city area is expanding with every passing day. Urbanisation is desired in almost every nation as it offers significant benefits, primarily acting as a powerful engine for economic growth and improved quality of life through better access to jobs, services and infrastructure. But beneath Dhaka's urban expansion lies a big concern --- rapid loss of green space, the most critical life-giving components. Rapid expansion leads to the destruction of the city's green landscape and the reduction of wetlands and open spaces for construction of roads, buildings and infrastructures, causing the city's balance with the environment to reach a critical stage. Several recent studies found that Dhaka's green space is degrading both in extension and quality.

Greenery is not just an aesthetic feature in the urban landscape. Trees, green spaces, meadows and wetlands serve as the lungs, kidneys, and temperature control systems of a city. In the case of Dhaka, the urban density, which is among the highest in the world, such natural systems are critical. However, over the last several decades, Dhaka has seen the loss of a substantial area of its tree cover and wetlands because of urbanisation and the lack of proper implementation of environmental legislation.

The city authorities have made different efforts to increase the tree cover area, including planting trees, but some of them turned into a futile exercise. A research found that the city is not benefiting much from the new tree plantation as most of the species are not native to Bangladesh and invasive. Authorities probably choose these trees as they are quick-growing, easier to maintain and considered to be ornamental in nature. But in reality, these species do little to provide any shade, absorb carbon dioxide, support bird or insect life, or cool any part of the city. In reality, in some cases, they cause a reverse effect, consuming excessive groundwater or failing to survive for long.

The impact of reduced or low-quality greenery on the urban environment is already apparent. No wonder, Dhaka is ranked consistently high among the most polluted cities in terms of air quality. Though it is true that vehicle exhaust, dust and industrial pollutants play roles detrimental to it, inadequate greenery is no less damaging. Trees purify the air by arresting particulate matter and absorbing harmful gases. The purification process is affected when there is not enough greenery.

The effect of this environmental degradation is profound. Poor air is directly linked to respiratory diseases like asthma, bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Cardiovascular diseases are also caused by the continuous intake of polluted air. According to health experts, thousands of people die prematurely each year in Dhaka as a result of air pollution.

To reverse the trend of declining greeneries in Dhaka, a mindset change is imperative. Green infrastructure should be considered vital public infrastructure and not a wish list. Urban forests, parks, and wetlands must be formally safeguarded and included in development plans. Tree-planting campaigns should be run every year to make people aware of the negative impacts of declining tree cover area. And authorities should focus on planting indigenous tree species like banyian, neem, jarul, and kadam since they grow well in the climate of Bangladesh, provide ample shade, and do not require much water.

Here in Surat, lots of plantation happens. Government Nursery distributes lots of plants. An NGO with whom I am associated has planted 25000 trees this rainy season. I planted 4000+ trees this season.