Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,136

- Likes

- 8,062

- Nation

- Axis Group

Will Rohingya crisis be resolved in near future?

Myanmar's military junta has dissolved its State Administration Council (SAC) and replaced it with a new interim caretaker setup, the so-called 'State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC)'. On July 31,2025, the February, 2021's coup leader, Senior General Ming Aung Hlaing lifted the state of emerge

Will Rohingya crisis be resolved in near future?

SYED FATTAHUL ALIM

Published :

Aug 18, 2025 01:03

Updated :

Aug 18, 2025 01:03

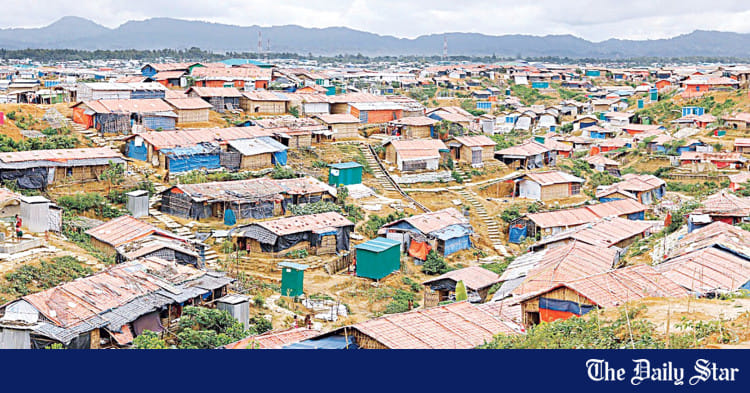

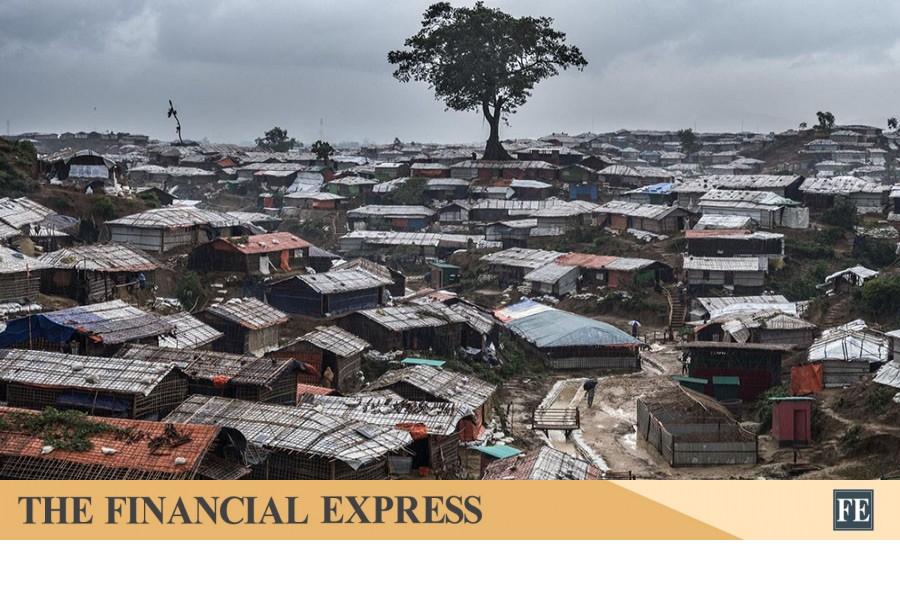

Rohingya refugees gather to mark the seventh anniversary of their fleeing from neighbouring Myanmar to escape a military crackdown in 2017, during heavy monsoon rains in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, August 25, 2024 — REUTERS Photo

Myanmar's military junta has dissolved its State Administration Council (SAC) and replaced it with a new interim caretaker setup, the so-called 'State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC)'. On July 31,2025, the February, 2021's coup leader, Senior General Ming Aung Hlaing lifted the state of emergency he had extended seven times to continue his regime's grip on Myanmar since he had toppled the country's elected government four and a half years ago. The aim of this move is to hold what junta leader calls an election 'on the path to a multiparty democracy' in December 2025 and January 2026.Interestingly, the junta on August 1, declared a new state of emergency and martial law on 63 townships across Myanmar including areas where ethnic armed groups and the National Unity Government (NUG) comprising lawmakers and members of parliament of the elected government deposed earlier by coup are now in control.

Clearly, this is an attempt by the Naypyidaw junta to present itself before the world in a new-look package. The election it plans to hold is nothing but a gimmick to hoodwink the world into believing that the new government to be formed after the so-called election will be a democratic one. Now the fact remains that the military junta in Naypyidaw is losing control on substantial parts of the country, especially in the border regions, to the rebels including, for example, the Arakan Army (AA), Ta'ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) etc. So, its authority over the country is increasingly coming into question. The rebel ethnic group armies already control large parts of the Rakhine, Shan, Kachin, Karen and Chin states. Also, a large chunk of Mandalay and Sagaingregions have gone under rebel occupation.

The Arakan Army (AA), for instance, controls some 270km of the Myanmar-Bangladesh border areas. It has meanwhile captured Paletwaand Buthidaungtowns bordering Bangladesh. In fact, the Naypyidaw junta still maintains control on major urban centres using its airpower such as in Sittwe, the capital of the Rakhine state.

Against this backdrop, the Bangladesh government has to rethink its strategy about who and how to deal with when it comes to repatriation of over 1.1 million Rohingya refugees in the overcrowded camps in Cox's Bazar with reports of arrivals of around 150,000 fresh waves of refugees during the last eighteen months. More importantly, until the ongoing civil war comes to an end, the authority of the current Naypyidaw government will remain questionable. So, even if any deal is reached with the Naypyidaw junta, its acceptability in the future will remain uncertain. Consider the offer made in April this year by the Myanmar authority on the sidelines of BIMSTEC meeting in Bangkok to take back 180,000 Rohingya refugees out of the list of some 800,000 Rohingya members that Bangladesh government submitted in six separate batches to the Myanmar authority between 2018 and 2020. But many Rohingya feared that the move by the Naypyidaw regime lacked necessary political will, security guarantees and restoration of citizenship as a prerequisite for their return. In response to that offer by Naypyidaw authority, King Maung, Executive Director of the Rohingya Youth Association (RYA), according to the news outlet, Rohingya Khobor, for instance, said, "We are not asking how many will return. If we are sent back without land, rights or recognition, it's not repatriation-it's re-persecution". 'We want justice, security, and our place in Arakan' Maung added.

Dr Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser to the interim government of Bangladesh, recently expressed his intention, as part of intensifying international efforts, to resolve the Rohingya crisis. To this end, three international conferences during this year would be held, he informed. Dr Yunus said this during a recent interview with the Malaysian national news agency, Bernama.

Dr Yunus is learnt to have further informed that the first of the conference would be held by the end of this August in Cox's Bazar, to mark the eighth year of the Rohingya's arrival on a large scale following 2017's ethnic cleansing campaign by the Myanmar government. The second conference will be held in September next on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly meeting. The third conference would be held by the year end in Doha, capital of Qatar.

Malaysia's leading role in Southeast Asia, especially as the head of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, (ASEAN), Dr Yunus believes, can play an important role in resolving the Rohingya crisis. It is worthwhile to note that the interim government since its assumption of office in early August 2024 has made a number of efforts towards mobilising international support to resolve the Rohingya issue. Notably, in November 2024, the interim government's lobbying resulted in a UN General Assembly resolution calling for a 'high-level conference' in the second half of 2025 to a 'comprehensive, innovative, concrete and time-bound plan for the sustainable resolution of the crisis including voluntary, safe and dignified return of Rohingya Muslims to Myanmar".

Given the ever-worsening conditions of the Rohingya in the cramped refugee shelters of Cox's Bazar and the international assistance for their sustenance dwindling to a trickle, international conferences are, of course, necessary if only to draw the global community's attention afresh to the near-forgotten Rohingya refugees Bangladesh has been playing host to for too long.

But mere talk at conferences will not be enough to ensure resettlement of the Rohingya that sought refuge in Bangladesh as well as at other places in their ancestral homeland. The international community needs also to play a strong role in seeing that the Myanmar civil war ends with transition to a civil government. At the same time, the international community brokering such transition in Myanmar should also include in its talks with the political stakeholders of Myanmar in question the accommodation of the Rohingya refugees and their secure, dignified and rightful return and resettlement in their homeland.

Bangladesh has been hosting about 1.2 million Rohingya refugees not only for the last eight years, but for decades after then-Myanmar government-engineered large-scale violence against and persecution of Rohingya leading to similar repatriation efforts in 1978 and 1992. In fact, pushing Rohingya people into Bangladesh has been a sinister design of successive governments in Myanmar whether civil or military, which betrayed Bangladesh government's weakness in handling the situation. What is necessary is to face them from a position of strength. Of course, it must get the international community on its side through astute diplomacy.

SYED FATTAHUL ALIM

Published :

Aug 18, 2025 01:03

Updated :

Aug 18, 2025 01:03

Rohingya refugees gather to mark the seventh anniversary of their fleeing from neighbouring Myanmar to escape a military crackdown in 2017, during heavy monsoon rains in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, August 25, 2024 — REUTERS Photo

Myanmar's military junta has dissolved its State Administration Council (SAC) and replaced it with a new interim caretaker setup, the so-called 'State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC)'. On July 31,2025, the February, 2021's coup leader, Senior General Ming Aung Hlaing lifted the state of emergency he had extended seven times to continue his regime's grip on Myanmar since he had toppled the country's elected government four and a half years ago. The aim of this move is to hold what junta leader calls an election 'on the path to a multiparty democracy' in December 2025 and January 2026.Interestingly, the junta on August 1, declared a new state of emergency and martial law on 63 townships across Myanmar including areas where ethnic armed groups and the National Unity Government (NUG) comprising lawmakers and members of parliament of the elected government deposed earlier by coup are now in control.

Clearly, this is an attempt by the Naypyidaw junta to present itself before the world in a new-look package. The election it plans to hold is nothing but a gimmick to hoodwink the world into believing that the new government to be formed after the so-called election will be a democratic one. Now the fact remains that the military junta in Naypyidaw is losing control on substantial parts of the country, especially in the border regions, to the rebels including, for example, the Arakan Army (AA), Ta'ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) etc. So, its authority over the country is increasingly coming into question. The rebel ethnic group armies already control large parts of the Rakhine, Shan, Kachin, Karen and Chin states. Also, a large chunk of Mandalay and Sagaingregions have gone under rebel occupation.

The Arakan Army (AA), for instance, controls some 270km of the Myanmar-Bangladesh border areas. It has meanwhile captured Paletwaand Buthidaungtowns bordering Bangladesh. In fact, the Naypyidaw junta still maintains control on major urban centres using its airpower such as in Sittwe, the capital of the Rakhine state.

Against this backdrop, the Bangladesh government has to rethink its strategy about who and how to deal with when it comes to repatriation of over 1.1 million Rohingya refugees in the overcrowded camps in Cox's Bazar with reports of arrivals of around 150,000 fresh waves of refugees during the last eighteen months. More importantly, until the ongoing civil war comes to an end, the authority of the current Naypyidaw government will remain questionable. So, even if any deal is reached with the Naypyidaw junta, its acceptability in the future will remain uncertain. Consider the offer made in April this year by the Myanmar authority on the sidelines of BIMSTEC meeting in Bangkok to take back 180,000 Rohingya refugees out of the list of some 800,000 Rohingya members that Bangladesh government submitted in six separate batches to the Myanmar authority between 2018 and 2020. But many Rohingya feared that the move by the Naypyidaw regime lacked necessary political will, security guarantees and restoration of citizenship as a prerequisite for their return. In response to that offer by Naypyidaw authority, King Maung, Executive Director of the Rohingya Youth Association (RYA), according to the news outlet, Rohingya Khobor, for instance, said, "We are not asking how many will return. If we are sent back without land, rights or recognition, it's not repatriation-it's re-persecution". 'We want justice, security, and our place in Arakan' Maung added.

Dr Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser to the interim government of Bangladesh, recently expressed his intention, as part of intensifying international efforts, to resolve the Rohingya crisis. To this end, three international conferences during this year would be held, he informed. Dr Yunus said this during a recent interview with the Malaysian national news agency, Bernama.

Dr Yunus is learnt to have further informed that the first of the conference would be held by the end of this August in Cox's Bazar, to mark the eighth year of the Rohingya's arrival on a large scale following 2017's ethnic cleansing campaign by the Myanmar government. The second conference will be held in September next on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly meeting. The third conference would be held by the year end in Doha, capital of Qatar.

Malaysia's leading role in Southeast Asia, especially as the head of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, (ASEAN), Dr Yunus believes, can play an important role in resolving the Rohingya crisis. It is worthwhile to note that the interim government since its assumption of office in early August 2024 has made a number of efforts towards mobilising international support to resolve the Rohingya issue. Notably, in November 2024, the interim government's lobbying resulted in a UN General Assembly resolution calling for a 'high-level conference' in the second half of 2025 to a 'comprehensive, innovative, concrete and time-bound plan for the sustainable resolution of the crisis including voluntary, safe and dignified return of Rohingya Muslims to Myanmar".

Given the ever-worsening conditions of the Rohingya in the cramped refugee shelters of Cox's Bazar and the international assistance for their sustenance dwindling to a trickle, international conferences are, of course, necessary if only to draw the global community's attention afresh to the near-forgotten Rohingya refugees Bangladesh has been playing host to for too long.

But mere talk at conferences will not be enough to ensure resettlement of the Rohingya that sought refuge in Bangladesh as well as at other places in their ancestral homeland. The international community needs also to play a strong role in seeing that the Myanmar civil war ends with transition to a civil government. At the same time, the international community brokering such transition in Myanmar should also include in its talks with the political stakeholders of Myanmar in question the accommodation of the Rohingya refugees and their secure, dignified and rightful return and resettlement in their homeland.

Bangladesh has been hosting about 1.2 million Rohingya refugees not only for the last eight years, but for decades after then-Myanmar government-engineered large-scale violence against and persecution of Rohingya leading to similar repatriation efforts in 1978 and 1992. In fact, pushing Rohingya people into Bangladesh has been a sinister design of successive governments in Myanmar whether civil or military, which betrayed Bangladesh government's weakness in handling the situation. What is necessary is to face them from a position of strength. Of course, it must get the international community on its side through astute diplomacy.