Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,880

- Likes

- 8,153

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Global trade moderation and Bangladesh

The calendar year 2025 is now set to enter its final month tomorrow. In other words, just a month from now, the world will see the start of another year. The annual stock-taking of global economic performance is already underway, although only relevant data for the first three quarters (January-Sep

Global trade moderation and Bangladesh

Asjadul Kibria

Published :

Nov 29, 2025 23:12

Updated :

Nov 29, 2025 23:49

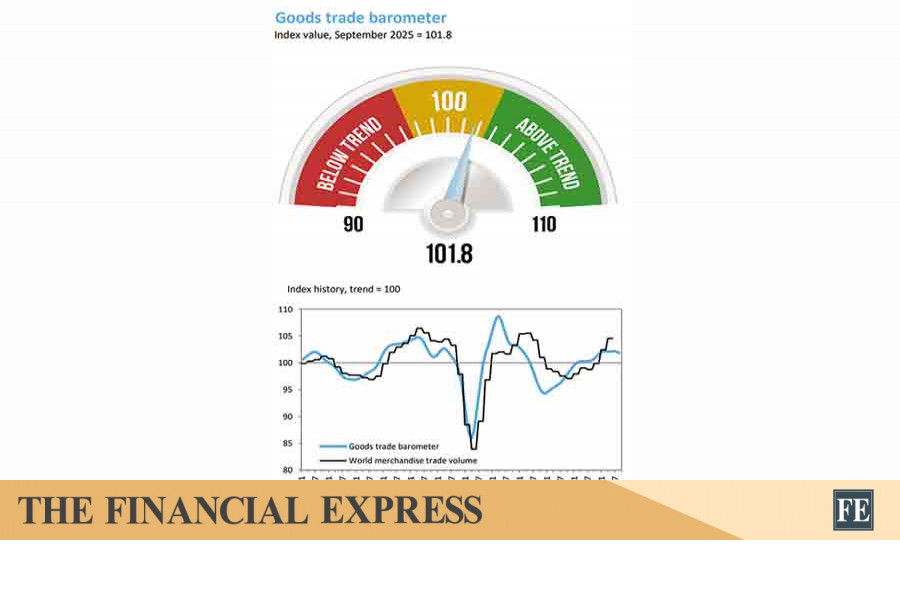

The calendar year 2025 is now set to enter its final month tomorrow. In other words, just a month from now, the world will see the start of another year. The annual stock-taking of global economic performance is already underway, although only relevant data for the first three quarters (January-September) is available. In this connection, the World Trade Organization (WTO) released the latest Goods Trade Barometer on Friday last. The barometer is a composite leading indicator for global trade that provides real-time information on the course of trade in goods relative to recent trends. Usually, the barometer predicts trade developments two to three months ahead. The latest barometer indicates a possible development of global trade in the last quarter of the current year.

The key message of the latest WTO Goods Trade Barometer is that global goods trade growth is set to moderate in the last quarter, leading to slower growth in the last half of the year. The surge in global trade in the first half was mainly driven by frontloading of imports ahead of expected tariff hikes and by rising demand for AI-related products, according to the barometer index analysis. The overall barometer index fell to 101.8 in September, down from 102.2 in June and below the quarterly trade volume index, which reflects actual merchandise trade developments.

There are six component indices of the barometer, and all are above their standard baseline value of 100 except for the agricultural raw materials index (98.0), which has been in contraction since the start of the year.

The indices for air freight (102.7) and container shipping (101.7) remain above trend. Nevertheless, these two indices have declined over the last three months, indicating a slowdown in global goods transportation. In other words, trade volume is likely to go through a downtrend in the coming days. The WTO last month predicted that merchandise trade, in terms of volume, may register 2.4 per cent growth in 2025 and 0.5 per cent in 2026. The slower growth projection is driven by higher tariffs and trade policy uncertainty in the second half of 2025 and in 2026.

The indices for automotive products (103.0) and electronic components (102.0) remained constant over the same period. It also indicates moderate growth prospects. Finally, the new export orders index (102.3) surpassed the baseline value of 100 in the second quarter, after some volatility at the end of 2024 and the start of 2025.

So, the overall reading of the indices suggests a moderation in global merchandise trade growth this year.

Earlier last month, the UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in its global trade update showed that the world trade expanded by about $500 billion in the first half of 2025, despite volatility, policy shifts and persistent geopolitical tensions. "Momentum remained strong into the third quarter, even as growth patterns varied across regions and sectors," it added.

UNCTAD also said that the trade growth continued in the third quarter, with goods expected to expand by about 2.5 per cent quarter over quarter and services accelerating sharply to around 4 per cent. As full data for the third quarter trade were not available at the time of releasing the UNCTAD update, the UN organisation issued a nowcast, a forecast of what is immediately expected, for the third quarter. It also said that barring major adverse shocks in the final months of 2025, global trade is projected to surpass its 2024 record levels. Last year, the value of global merchandise trade stood at US$24.5 trillion, posting modest growth of 2 per cent over 2023.

UNCTAD was of the view that despite turbulence from shifting US trade policy, global trade dynamics have so far shown limited disruption. However, uncertainty over future policy remains a key risk. "Geopolitical instability also continues to weigh on trade, with persistent conflicts that could further disrupt regional dynamics and heighten concerns over energy and food security," it added in its October update report.

The moderation of the global trade in goods will also impact countries like Bangladesh as their exports are dependent on the movement of the global market. Already, the country's trade in goods registered a modest 2 per cent growth in the first nine months of the current year over the previous year. Statistics available with Bangladesh Bank showed that total trade in the January-September period of 2025 stood at $82.79 billion, which was $81.14 billion in the same period of 2024.

The official statistics also showed that merchandise exports of the country increased by 4.74 per cent in the first nine months of the current year, whereas the imports remained almost the same, reflecting weak domestic demand.

As the country enters the election-centric political business cycle, weak domestic demand will persist for a couple of months before and after the election in February of the next year. While the import is correlated with domestic demand, the export is linked to the international market, which has already become somewhat volatile due to Trump's tariff policy.

The US President initially imposed a 35 per cent reciprocal tariff on Bangladesh, which later fell to 20 per cent after hectic negotiations with several commercial offers to the US. The new tariff rate comes into effect in August, and the primary impact will be visible by the end of the year.

As China is the leading trade partner, mainly because it is the largest source of imports in Bangladesh, despite a decline in domestic demand, total imports from China will post moderate growth by the end of the year.

Overall, Bangladesh is going to witness a year of sluggish trade in goods which will have some negative impact on the growth of country's gross domestic product (GDP).

Asjadul Kibria

Published :

Nov 29, 2025 23:12

Updated :

Nov 29, 2025 23:49

The calendar year 2025 is now set to enter its final month tomorrow. In other words, just a month from now, the world will see the start of another year. The annual stock-taking of global economic performance is already underway, although only relevant data for the first three quarters (January-September) is available. In this connection, the World Trade Organization (WTO) released the latest Goods Trade Barometer on Friday last. The barometer is a composite leading indicator for global trade that provides real-time information on the course of trade in goods relative to recent trends. Usually, the barometer predicts trade developments two to three months ahead. The latest barometer indicates a possible development of global trade in the last quarter of the current year.

The key message of the latest WTO Goods Trade Barometer is that global goods trade growth is set to moderate in the last quarter, leading to slower growth in the last half of the year. The surge in global trade in the first half was mainly driven by frontloading of imports ahead of expected tariff hikes and by rising demand for AI-related products, according to the barometer index analysis. The overall barometer index fell to 101.8 in September, down from 102.2 in June and below the quarterly trade volume index, which reflects actual merchandise trade developments.

There are six component indices of the barometer, and all are above their standard baseline value of 100 except for the agricultural raw materials index (98.0), which has been in contraction since the start of the year.

The indices for air freight (102.7) and container shipping (101.7) remain above trend. Nevertheless, these two indices have declined over the last three months, indicating a slowdown in global goods transportation. In other words, trade volume is likely to go through a downtrend in the coming days. The WTO last month predicted that merchandise trade, in terms of volume, may register 2.4 per cent growth in 2025 and 0.5 per cent in 2026. The slower growth projection is driven by higher tariffs and trade policy uncertainty in the second half of 2025 and in 2026.

The indices for automotive products (103.0) and electronic components (102.0) remained constant over the same period. It also indicates moderate growth prospects. Finally, the new export orders index (102.3) surpassed the baseline value of 100 in the second quarter, after some volatility at the end of 2024 and the start of 2025.

So, the overall reading of the indices suggests a moderation in global merchandise trade growth this year.

Earlier last month, the UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in its global trade update showed that the world trade expanded by about $500 billion in the first half of 2025, despite volatility, policy shifts and persistent geopolitical tensions. "Momentum remained strong into the third quarter, even as growth patterns varied across regions and sectors," it added.

UNCTAD also said that the trade growth continued in the third quarter, with goods expected to expand by about 2.5 per cent quarter over quarter and services accelerating sharply to around 4 per cent. As full data for the third quarter trade were not available at the time of releasing the UNCTAD update, the UN organisation issued a nowcast, a forecast of what is immediately expected, for the third quarter. It also said that barring major adverse shocks in the final months of 2025, global trade is projected to surpass its 2024 record levels. Last year, the value of global merchandise trade stood at US$24.5 trillion, posting modest growth of 2 per cent over 2023.

UNCTAD was of the view that despite turbulence from shifting US trade policy, global trade dynamics have so far shown limited disruption. However, uncertainty over future policy remains a key risk. "Geopolitical instability also continues to weigh on trade, with persistent conflicts that could further disrupt regional dynamics and heighten concerns over energy and food security," it added in its October update report.

The moderation of the global trade in goods will also impact countries like Bangladesh as their exports are dependent on the movement of the global market. Already, the country's trade in goods registered a modest 2 per cent growth in the first nine months of the current year over the previous year. Statistics available with Bangladesh Bank showed that total trade in the January-September period of 2025 stood at $82.79 billion, which was $81.14 billion in the same period of 2024.

The official statistics also showed that merchandise exports of the country increased by 4.74 per cent in the first nine months of the current year, whereas the imports remained almost the same, reflecting weak domestic demand.

As the country enters the election-centric political business cycle, weak domestic demand will persist for a couple of months before and after the election in February of the next year. While the import is correlated with domestic demand, the export is linked to the international market, which has already become somewhat volatile due to Trump's tariff policy.

The US President initially imposed a 35 per cent reciprocal tariff on Bangladesh, which later fell to 20 per cent after hectic negotiations with several commercial offers to the US. The new tariff rate comes into effect in August, and the primary impact will be visible by the end of the year.

As China is the leading trade partner, mainly because it is the largest source of imports in Bangladesh, despite a decline in domestic demand, total imports from China will post moderate growth by the end of the year.

Overall, Bangladesh is going to witness a year of sluggish trade in goods which will have some negative impact on the growth of country's gross domestic product (GDP).