Ending discretionary oversight: Why Bangladesh needs rule-based trade monitoring

How effectively can a central bank detect misinvoicing using manual tools and human judgment alone? FILE PHOTO: STAR

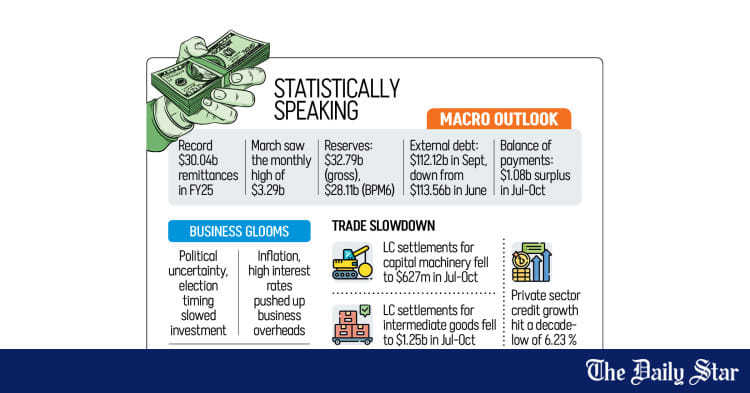

The controversy surrounding under-invoicing surfaced as a flagship achievement of the Bangladesh Bank leadership during the previous regime. At that time, the central bank proudly declared that it had uncovered large-scale import mispricing, taking credit for identifying irregularities that were said to be draining foreign exchange from the economy. The narrative was simple: under-invoicing and over-invoicing were distorting the external account, encouraging capital flight, and weakening the local currency. The solution, it was claimed, lay in aggressive monitoring and strict interrogation of import declarations. That narrative, however, had broader economic implications that were not fully considered.

By mid-2022, the taka faced one of its most serious crises in decades. A confluence of global commodity shocks, supply chain disruptions, declining reserves, and domestic economic imbalances led to a sharp depreciation. In response, a wide range of administrative measures was introduced. Some were necessary, but many were reactive and lacked strategic coherence. Import monitoring became unusually intensive. Banks were required to submit detailed import information for transactions of $3 million or more, at least 24 hours before initiating imports. The central bank formed internal teams to scrutinise these submissions, examining declared prices against its own reference scales. Banks and importers were often summoned to justify deviations. What was presented as regulatory oversight gradually became, in many eyes, an intimidating process.

As per industry insiders, officials of the central bank tasked with identifying mispricing often took a confrontational approach. Commercial bank officials were repeatedly asked to explain price differentials for thousands of items, even though international prices regularly fluctuate due to shipment conditions, contract terms, trade credit arrangements, insurance costs, and quality differences. The importers, too, felt they were being treated as suspects rather than stakeholders in trade facilitation. In an environment where businesses were already struggling with uncertain exchange rates and shortages of foreign currency, the added burden only compounded difficulties for importers.

The stated goal was noble: to detect and curb misinvoicing. In theory, misinvoicing is a reality in many developing economies. It can distort national statistics, leak foreign exchange, and provide avenues for illicit financial flows. Yet the question remains: how effectively can a central bank detect misinvoicing using manual tools and human judgment alone? Modern practice suggests that a rule-based, data-driven, and technology-enabled approach is essential. Bangladesh, however, was attempting to detect complex trade mispricing through methods that are inherently subjective and prone to inconsistencies.

After the regime change, businesses expected a shift away from the earlier confrontational style. The new governor held meetings with major commodity importers. They pointed out that the old system of price verification was still very much alive, with teams continuing to call banks and importers for explanations, as per the media. They argued that such regulatory behaviour was not only impractical but also unfair. Global commodity markets move daily, sometimes hourly. Freight charges change by season. Supplier terms differ across countries. Without access to high-quality global price databases, real-time analytics, and properly trained investigators, none of these variances can be accurately interpreted. The governor reportedly assured importers that the process would be simplified. Yet businesses claim the same informal interrogations continue. This suggests that institutional culture, once established, does not change automatically—it must be replaced with a rules-based framework that restricts individual discretion.

The broader question is whether misinvoicing can realistically be detected by a central bank through ex-ante document review. Theoretically, yes. Many global institutions use sophisticated tools such as trade-pricing databases, automated red-flag systems, machine learning models, and cross-border information exchange. But the operative word is "sophisticated." Without proper digital infrastructure, experienced analysts, and well-implemented trade-data interfaces, price verification risks becoming arbitrary. It may capture unusual cases, but more often it produces false alarms, leading to unnecessary harassment.

A central bank's core role is to maintain monetary and financial stability. It is not designed to be an investigative agency policing every invoice that enters the country. When it attempts to take on tasks without proper institutional tools, the result is inefficiency and erosion of trust—both in the banking system and in the wider regulatory framework. No major economy conducts invoice-level policing as a routine practice. Instead, they rely on risk-based compliance systems, automated data triangulation, and post-transaction audit trails. Bangladesh must move in the same direction.

The case for a rule-based approach is strong. First, it eliminates discretion. When rules are clearly defined and automated systems flag anomalies based strictly on data, the scope for subjective interpretation diminishes. Businesses get clarity. Banks realise the limits of their obligations. Regulators reduce the risk of bias or allegations of undue pressure. Second, rules minimise operational burden. Millions of import documents enter the system every year. No central bank team, however large, can manually examine each one. A system that automatically compares declared values with global indices and identifies deviations beyond a predefined margin can process information without human fatigue.

Third, rule-based systems enhance credibility. Investors and global institutions view predictable regulatory environments favourably. When decisions appear personal, unpredictable, or discretionary, confidence erodes. This affects investment flows, trade credit, and the overall business climate. Fourth, rule-based oversight supports economic efficiency. When businesses spend excessive time responding to regulatory queries, operational costs increase. Imports are delayed. Supply chains slow down. In critical sectors such as food, energy, and industrial inputs, even a short delay can translate into shortages or price spikes in the domestic market.

There is also an important governance dimension. Harassment—perceived or real—undermines institutional image. It creates a fear-driven culture of compliance instead of a trust-based one. Regulators should encourage voluntary compliance rather than create a climate where businesses feel compelled to defend themselves against accusations not backed by evidence. Central bank officials cannot rely on "gut feeling" to accuse an importer of mispricing. They must rely on structured data, documented analysis, and internationally recognised methodologies.

To transition towards such a system, Bangladesh needs several reforms. First, the introduction of a global price reference database linked to customs, port authorities, banks, and the central bank. Systems such as UN Comtrade, the International Trade Centre's Market Price Information, and global commodity index feeds can be integrated with domestic trade records. This would allow automated comparison of declared values with worldwide benchmarks adjusted for freight, insurance, quality, and market volatility.

Second, a digital trade-data platform is essential. All banks should be connected to a central trade monitoring hub where import declarations, letters of credit (LCs), shipping documents, and customs declarations are automatically compared. Any irregularities can be flagged digitally, allowing regulators to focus only on high-risk cases.

Third, a post-transaction risk-based audit framework should replace pre-transaction interrogation. This aligns with global best practice. Instead of stopping transactions before they occur, the central bank can review a sample of completed transactions using a scoring model. Only those that show strong red flags should trigger detailed inquiries. This would eliminate the need for importers to justify prices for every single deal.

Fourth, the central bank's investigative role should be clearly delimited. Customs authorities, tax agencies, and financial intelligence units already have mandates for detecting illicit activities. Overlapping responsibilities create confusion and compliance fatigue. The central bank should confine its oversight to areas directly related to foreign exchange regulations and banking operations.

Finally, accountability mechanisms must be strengthened. If businesses face undue harassment, there should be an appeal process. Independent review committees can examine disputes, ensuring fairness and transparency. A regulator must itself be subject to rules. Institutions, not individuals, should govern.

The current governor's willingness to engage with importers is a positive signal. Dialogue is essential, but reforms must reflect structural changes rather than policy statements alone. Bangladesh's external sector is gradually stabilising after the 2022 shock. Foreign exchange liquidity has improved. Import payment backlogs have normalised. This is the right moment to modernise regulatory processes and eliminate outdated practices. A central bank should inspire confidence, not fear. Businesses should feel protected, not threatened.

The ghost of the past regulatory regime should not overshadow present progress. Legacy practices survive when they are not formally replaced. That is why Bangladesh must adopt a forward-looking regulatory philosophy: rule-based, technology-enabled, and supportive of trade competitiveness. A country aspiring to become a trillion dollar economy cannot afford to operate with manual, subjective, or personality-driven oversight. It needs strong institutions delivering predictable outcomes. Oversight must be firm but fair. For Bangladesh to build a resilient external sector, regulatory modernisation is not optional—it is imperative.

Tashzid Reza works in a trade finance company operating as a liaison office in Bangladesh.