Trade pact or template for control over Bangladesh?

M G Quibria

Published :

Feb 15, 2026 22:47

Updated :

Feb 15, 2026 22:47

The cloak of secrecy has finally been lifted. The non-disclosure agreement that kept the Bangladesh-US "reciprocal tariff" deal hidden from public scrutiny has been pulled back, and Bangladeshis can now see what was negotiated in their name. On first reading, this does not look like an agreement between sovereign equals. It reads like a document drafted in Washington and handed over for signature. If Bangladesh had trade lawyers and economists at the table, they were either absent or overruled. The result is deeply concerning.

What emerges is not "reciprocity" in any meaningful sense. It is a framework of conditionality backed by enforcement: Bangladesh commits to sweeping changes across trade regulation, digital policy, agriculture, procurement, and even security alignment, while the United States (US) retains the ultimate lever-a tariff snapback mechanism that can be triggered if Washington decides Bangladesh is not "complying."

The following highlights some of the features of the trade agreement.

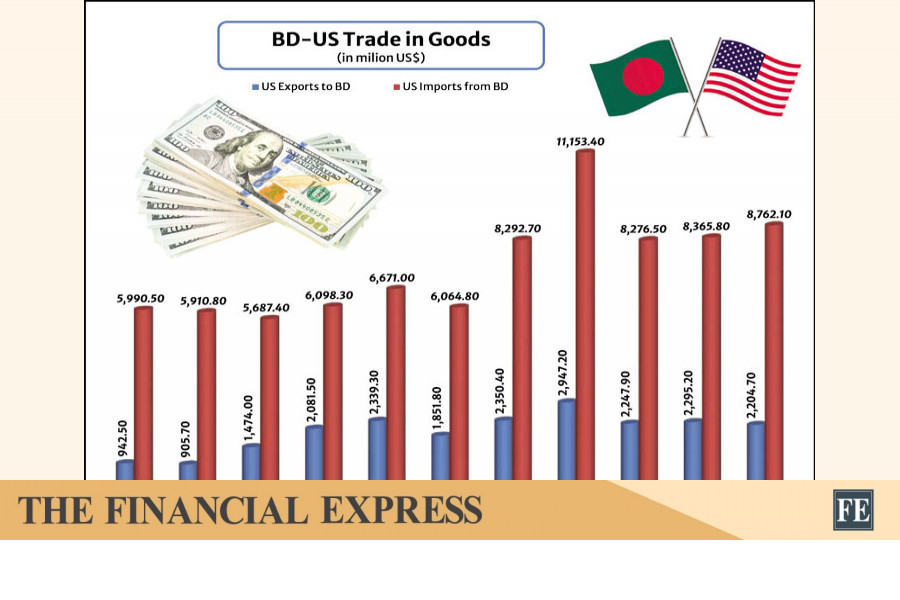

THE TARIFF THREAT THAT NEVER GOES AWAY: Here is how it works: The US agrees to reduce its tariff on most Bangladeshi goods to 19 per cent, down from a threatened 37 per cent [Schedule 2 to Annex I]. For one product category-Bangladeshi garments made with American cotton and man-made fiber-the tariff drops to zero, but the agreement does not specify how much can qualify for this benefit, leaving exporters uncertain about this key concession.

Sounds good? Here is the catch: The US can snap these tariffs back at any time if it finds Bangladesh is not "complying" [Article 6.4]. And compliance does not just mean following trade rules. The US can re-impose tariffs if Bangladesh signs a trade agreement with China or any other "non-market country," makes a digital economy deal with a country the US does not like [Article 3.2], or fails to "resolve concerns" in consultations on virtually anything.

Bangladesh's garment exporters, the backbone of the economy, would live under constant threat: follow American demands on everything from domestic laws to foreign policy or watch your export business collapse overnight.

FOLLOW OUR ENEMIES, LOSE YOUR MARKET ACCESS: The most troubling part is how the deal forces Bangladesh to pick sides in global conflicts that have nothing to do with Bangladesh.

If the US imposes trade restrictions on another country for "economic or national security" reasons, Bangladesh must impose similar restrictions [Article 4.1]. In plain language: when America punishes China or Russia, Bangladesh must join in-even if it hurts Bangladesh's own interests.

It gets worse. Bangladesh must "harmonize" its export controls with American export controls, help enforce US sanctions by treating violations of American sanctions as if they were violations of Bangladeshi law, screen all exports for items controlled by the US and share that data with Washington, and create criminal penalties for violating US export control laws [Article 4.2 and Section 3 of Annex III].

This is not about protecting Bangladesh. It is about turning Bangladesh into an enforcement arm of American foreign policy.

YOU CAN'T MAKE DEALS WE DON'T LIKE: The agreement does not just control what Bangladesh does-it controls what deals Bangladesh can make with other countries.

Bangladesh cannot sign agreements with other countries that use technical standards "incompatible" with US standards, include health and safety measures that "disadvantage U.S. exports," or that the U.S. simply does not like [Article 2.3].

Want a free trade agreement with China? The US can terminate the deal and bring back tariffs [Article 4.3.4]. Want to buy nuclear reactors from Russia or China for power generation? Explicitly prohibited [Article 4.3.5]. Want digital economy partnerships with countries the U.S. considers rivals? Agreement terminated [Article 3.2].

The United States has given itself veto power over Bangladesh's economic relationships with the rest of the world.

REWRITING BANGLADESH'S LAWS FROM WASHINGTON: Beyond trade, the agreement tells Bangladesh exactly how to write its own laws. This is unprecedented micromanagement.

On labor laws, Bangladesh must amend the Bangladesh Labour Act to lower union registration requirements from 20 per cent to some unspecified lower threshold, remove the ability to cancel union registration without court approval, increase fines for anti-union discrimination to "sufficient levels" (left undefined), remove imprisonment penalties for strikes, make export processing zones subject to labor laws within two years, and drop criminal cases against workers from the 2023 wage protests [Article 1.19 of Annex III].

On digital laws, Bangladesh must amend or completely repeal its 2021 social media regulation, remove requirements for companies to hand over encryption keys, and amend the Cyber Safety Act to incorporate "freedom of expression protections." [Section 2.4 of Annex III].

On environmental laws, Bangladesh must accept the World Trade Organization (WTO) fisheries agreement without the exemptions normally granted to developing countries, submit specific forestry legislation to international bodies, and implement detailed requirements to combat illegal logging [Articles 1.20-1.26 of Annex III].

These are not high-level principles. These are line-by-line instructions on how to write Bangladeshi law-backed by the threat that if Bangladesh does not comply, tariffs will be reinstated.

THE GMO TRAP- AUTOMATIC APPROVAL WITHOUT REVIEW: Here is a provision that could cause serious domestic problems: Within 24 months, Bangladesh must automatically accept any genetically modified agricultural product approved in the United States-without conducting its own safety review and without requiring labels [Article 1.6 of Annex III].

Think about what this means. If it is approved by US regulators, it must be allowed into Bangladesh. Bangladesh cannot require independent testing. Bangladesh cannot require labels telling consumers the food is genetically modified. Bangladesh must accept trace amounts of GM material without delay, relying on US safety assessments.

In many parts of the world, including South Asia, GMO food is intensely controversial. Consumers do not trust it, farmers fear it, and courts have ruled on it. Bangladesh is being locked into a system that could trigger massive public backlash.

TRADING AWAY CONTROL OF TRADE POSITIONS: The agreement even scripts what Bangladesh can say at the WTO in Geneva.

Bangladesh must "support multilateral adoption of a permanent moratorium" on tariffs for digital products [Article 3.3]. This is a contested issue where developing countries worry about losing future tax revenue as commerce goes digital. Whether you agree with the moratorium or not, Bangladesh should not have to promise its vote in a bilateral deal-especially one where the US can re- impose tariffs if Bangladesh does not deliver.

Bangladesh must also accept the WTO Fisheries Subsidies Agreement "notwithstanding Article 12"-the clause that gives developing countries flexibility. In other words: accept it without the exemptions developing countries normally get [Article 1.23 of Annex III].

And Bangladesh must submit a complete list of all subsidies it provides to the WTO within six months [Section 6.5 of Annex III]. Transparency is fine, but when there is a tariff gun pointed at your head, it is not cooperation--it is coercion.

THE SHOPPING LIST -- PLANES, GAS, AND SOYBEANS: The deal then becomes a procurement ledger. Bangladesh "shall endeavor" to facilitate purchases of US aircraft. It "shall endeavor" to purchase or facilitate the purchase of U.S. energy, including LNG. It "shall endeavor" to purchase US agricultural products-wheat, soy, cotton-down to specific values and quantities [ Section 6 of Annex III].

This shopping list includes: 25 Boeing aircraft for Biman (14 firm orders plus options), worth Tk 30,000-35,000 crore; $15 billion in U.S. liquefied natural gas over 15 years; $3.5 billion in agricultural products including 700,000 tons of wheat yearly for five years, $1.25 billion in soybeans, plus cotton; increased purchases of U.S. military equipment; and limits on buying military equipment from "certain countries"(read: China, among others).

Here is the problem with the aircraft purchase: Biman Bangladesh Airlines is losing money. Its officials say they were not even consulted about this commitment; they learned about it from the media. The airline's technical committee was still evaluating proposals from both Boeing and its European competitor, Airbus.

When a state airline is bleeding cash, buying planes is not about expanding service; it is about taking on debt guaranteed by the government and paid in scarce foreign exchange. At a time when Bangladesh's reserves are under pressure, locking in a $3-4 billion aircraft purchase to satisfy a trade deal is not economic policy. It is surrendering fiscal sovereignty.

If Bangladesh needs planes, the decision should be based on route profitability, fleet requirements, and financial sustainability-not because Washington wants export sales and can threaten tariffs if Bangladesh buys from Europe instead.

THE CARROT-ZERO TARIFFS FOR GARMENTS WITH US COTTON: The agreement does offer one significant benefit: Bangladeshi garments made with US cotton and man-made fiber will get zero tariffs in the American market.

This is valuable. It could give Bangladesh's garment sector-which employs millions-a competitive edge. The problem? The agreement does not specify how much can qualify. There is a promise of a "mechanism" that will determine volume "in relation to" how much U.S. textile input Bangladesh imports-but the details are not set.

THE BOTTOM LINE: Bangladesh does not need conflict with the United States. But it needs negotiators who understand that what is on paper now is not a trade agreement, it is a framework for subordination.

The agreement curbs Bangladesh's ability to write its own laws, choose its trading partners, set its foreign policy, and manage its budget. It gives the US multiple off-ramps to cancel the deal and reimpose tariffs-not just for trade violations, but for sovereign choices Washington dislikes.This is what happens when a weaker country negotiates from a position of desperation rather than strength. The lesson is not just about this agreement. It is about state capacity: if you cannot defend your interests at the negotiating table, others will define them for you. And they will define them in ways that serve their interests, not yours.

[Note: This analysis references the U.S.-Bangladesh Agreement on Reciprocal Trade(

https://ustr.gov/sites/default/file...n Reciprocal Trade Final 09FEB2026 LETTER.pdf), signed February 9, 2026. Article citations appear in square brackets.]

Dr M G Quibria is a trade and development economist whose career bridges international development and academia.