Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,300

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

From hydro-coercion to water justice

Teesta has led to the collapse of traditional livelihoods in fishing and agriculture.

From hydro-coercion to water justice

Why the Ganges Treaty and shared rivers demand a new imagination

The transboundary journey of the Ganges, flowing from the Himalayan foothills through Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal before entering Bangladesh.

"There once was a river here." Across the Bengal Delta, this lament has become a hauntingly common refrain, signalling a transformation that is as much political as it is environmental. For Bangladesh, water is far more than a resource; it is the vital pulse of our ecological resilience and the primary determinant of our human vulnerability. Yet, in the high-stakes geopolitical landscape of South Asia, our rivers are increasingly being reconfigured from lifelines into instruments of hydro-coercion. As we stand at a historic junction, marked by the aftermath of the July 2024 revolution and the looming 2026 expiration of the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty, it is time to address the big picture of our water security. We must move beyond a legacy of downstream capitulation towards a future of water justice grounded in the recognition of our rivers as ecological commons.

The July 2024 uprising in Bangladesh did more than just overthrow a regime; it fundamentally altered the political foundations that had, for sixteen years, enabled India's hydro-coercive practices. Under the previous India-backed administration, Bangladesh often adopted a subservient posture in which domestic political legitimacy was essentially traded for Indian diplomatic patronage. This political accommodation created a dangerous feedback loop where our leadership avoided confronting treaty violations or upstream unilateralism in order to preserve broader bilateral ties. The revolution represented a conceivable rupture in this pattern of downstream capitulation. The popular uprising was fuelled by a deep-seated resentment against what many perceived as imperial control over domestic sovereignty, with water often serving as the primary tool of that control. Today, there is a burgeoning demand from the youth movement and civil society to decolonise our water governance and to challenge the colonial logics that have long normalised the advantage of upstream riparians at the expense of our survival.

To navigate this new era, we must understand what I have described as hydro-coercion, a strategic evolution of hydro-hegemony. While hydro-hegemony describes a general state of dominance in which a riparian state uses power to secure water objectives, hydro-coercion is the active weaponisation of water control for immediate and long-term political objectives. It functions as a mechanism of escalating spatial and geopolitical domination, where the upstream state exerts direct or indirect pressure on downstream states to force compliance. In the India–Bangladesh context, this power is deployed through three distinct but overlapping strategies that amount to a form of political colonisation.

The first of these is material hydro-coercion, which involves the physical control of water resources through large-scale infrastructure to reconfigure deltaic hydro-social territories. The Farakka Barrage is the most potent and enduring symbol of this material dominance. Commissioned in 1975 without meaningful consultation or consent from Bangladesh, the barrage unilaterally diverts dry-season flows. This infrastructure is not merely a technical solution for navigability but an enduring instrument of control that embeds hydro-insecurity into our national consciousness. By physically altering the flow of the Ganges, India uses its geographical advantage to impose a reality of scarcity upon the downstream delta, effectively redrawing the social and ecological map of the region to suit its own interests.

The Farakka Barrage in West Bengal stands as the primary site of upstream water control on the Ganges.

The second dimension is institutional hydro-coercion, which operates through procedural manipulation, bargaining power, and what can be described as institutional stalling. The prolonged stalemate over the Teesta River is a clear instance of this strategy. Although an agreement was nearly finalised in 2011, it has been blocked for over a decade by the state government of West Bengal. This subnational veto allows the Indian federal government to avoid accountability for diplomatic failure while implicitly using the unresolved issue as leverage. This manufactured scarcity is a deliberate strategic delay in which non-decision and silence are weaponised as forms of structural power. By keeping Bangladesh in a state of perpetual negotiation and vulnerability, India maintains an advantageous position that pressures our nation into broader strategic alignment.

The third pillar is ideational hydro-coercion, which utilises water nationalism and diplomatic signalling to shape narratives of sovereignty and development. Water is imbued with powerful nationalistic meanings, transforming it from a natural resource into a symbol of national identity that justifies unilateral extraction. India frames its upstream schemes as essential to its national progress, often characterising downstream claims as impediments to its sovereign prerogatives. This ideational control extends to overt diplomatic pressure; for example, recent reports indicate that Indian politicians have suggested the 1996 Ganges Treaty could be reconsidered if Bangladesh's foreign policy diverges from Indian interests. Such statements explicitly link vital water access to foreign policy compliance, using water as a tool of deterrence to prevent Bangladesh from pursuing strategic autonomy or closer ties with other regional powers.

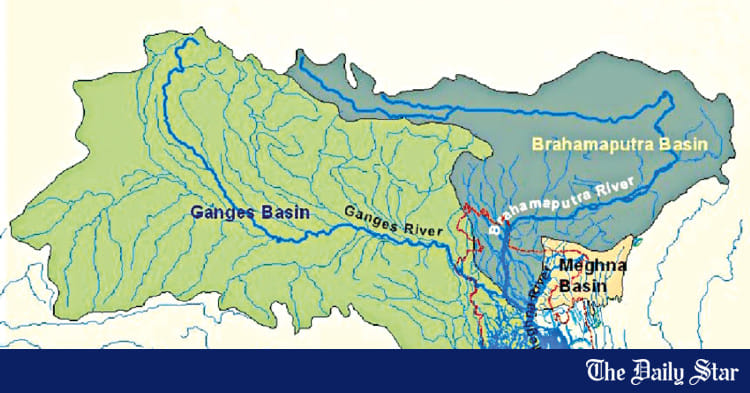

Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) Basin

The consequences of these coercive practices are not abstract theories but lived realities of pervasive precarity for millions of Bangladeshis. The diversion of the Ganges has led to severe salinity intrusion in our coastal regions, devastating agricultural lands and compromising potable water sources. This ecological degradation directly threatens the Sundarbans, which is the world's largest mangrove forest and our primary defence against climate-induced cyclones. In the north, the lack of predictable flow from the Teesta has led to the collapse of traditional livelihoods in fishing and agriculture. These disruptions drive internal migration and displacement, as rural communities are forced to abandon their ancestral lands for the precarious life of urban slums. This displacement is a form of structural violence, where hegemonic control over water fuels the redrafting of the social fabric of our nation.

This structural inequality is reaching a breaking point due to the threat multiplier of climate change. We are entering an era of unprecedented hydro-variability, where Himalayan glaciers are projected to decline by up to 40 percent by 2100. For Bangladesh, this means a future of catastrophic monsoon floods followed by acute dry-season scarcity. Our existing agreements, particularly the 1996 Ganges Treaty, are tragically ill-equipped for this volatility. The treaty treats water as a divisible commodity to be quantified and allocated based on historical data rather than as a shared, interconnected ecological system. It lacks flexible mechanisms for climate adaptation, enforceable environmental flow regimes, or joint data-sharing platforms. As the treaty approaches its 2026 expiration, we must realise that a static agreement is no longer a tool of cooperation; in a climate-stressed world, it becomes another mechanism of control.

It is a mistake to view water justice as a zero-sum game, because from a strategic perspective, hydro-coercion is self-defeating for India. A water-stressed, ecologically fragile Bangladesh is a source of regional instability. The cascading effects of environmental degradation, including mass migration, state fragility, and economic shocks, do not respect national borders. Furthermore, the regional power dynamic is shifting, as China's aggressive dam-building on the upper Brahmaputra creates a cascading hierarchy in which India itself is vulnerable to upstream control. If India continues to adopt a coercive posture towards its downstream neighbour, it weakens its own moral and legal standing when challenging Chinese unilateralism. True regional stability requires cooperative precedents rather than coercive ones.

Beyond the immediate concerns of water flow, the health of the India–Bangladesh relationship is foundational to broader regional prosperity across the energy, trade, and transportation sectors. Bangladesh provides critical transit and transhipment facilities that connect India's northeastern states to its mainland, while India is a major source of the electricity and consumer goods that fuel our economy. These sectors are deeply interdependent, yet this interdependence is poisoned by the mistrust generated by hydro-coercion. When water is used as a diplomatic lever, it creates a climate of uncertainty that hinders long-term investment in regional connectivity and energy grids. For instance, the vision of a seamless South Asian power pool, where hydroelectricity from Nepal and Bhutan flows through India to Bangladesh, cannot be realised if the participating nations remain locked in hydro-political disputes. Stable, neighbourly relations are not a luxury but a prerequisite for the economic integration that could lift millions out of poverty across the entire basin.

The path forward requires a fundamental structural transformation in how we govern our transboundary waters. We must move beyond narrow, secretive bilateral negotiations towards comprehensive basin-wide governance. This means involving all riparian states, including Nepal, Bhutan, India, and China, in holistic planning for our shared river systems. Bangladesh's June 2025 entry into the UNECE Water Convention is a critical first step in this strategic pivot, anchoring our claims in international legal norms of equitable and reasonable utilisation. This multilateral shift provides a normative basis to challenge unilateral actions and assert our downstream rights in a way that bilateralism never could.

Transformative governance also necessitates the establishment of enforceable ecological safeguards. Future treaties must recognise the intrinsic value of water and include legally binding minimum environmental flow regimes to protect the health of our rivers and the biodiversity of the delta. Alongside these safeguards, we must demand drastic data transparency. The current information asymmetry is a tool of coercion, and we must insist on the mandatory, real-time sharing of hydrological and climate data. This is foundational for building trust, creating early warning systems, and ensuring collaborative management in an era of climate uncertainty. Most importantly, we must shift the discourse from water as a diplomatic concession to water as a fundamental human right. Access to water for basic needs, livelihoods, and ecological sustenance must be non-negotiable.

The upcoming expiration of the Ganges Treaty in 2026 is our most significant strategic inflection point. We cannot afford to passively await upstream goodwill while our rivers dwindle. We must use this moment to demand an epistemic rupture, which is a break from the colonial-era logic of extraction and control. The rivers of the Bengal Delta are an ecological commons and a shared heritage that demands collective stewardship rather than competitive exploitation. By centring the voices of downstream communities and grounding our governance in ecological justice and the principles of the ecological commons, we can turn our shared rivers into sources of regional strength.

For a deltaic nation like Bangladesh, achieving water justice is not merely a goal of foreign policy; it is the absolute prerequisite for our survival. Sustainable water governance cannot rest upon the political subordination of downstream populations. If we are to ensure a stable and prosperous South Asia, we must move towards a future where shared rivers foster genuine cooperation and resilience rather than remaining potent symbols of power imbalance and perennial conflict. Only by radically changing our approach to water and embracing the principles of joint basin stewardship can we hope to preserve the lifeblood of our delta for generations to come. An equitable water future is the only path towards the regional peace and human security that our people so urgently deserve.

Farhana Sultana, PhD, is Professor of Geography and the Environment at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, USA. Her research focuses on the intersections of water governance, climate justice, and international development, with particular attention to South Asia.

Why the Ganges Treaty and shared rivers demand a new imagination

The transboundary journey of the Ganges, flowing from the Himalayan foothills through Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal before entering Bangladesh.

"There once was a river here." Across the Bengal Delta, this lament has become a hauntingly common refrain, signalling a transformation that is as much political as it is environmental. For Bangladesh, water is far more than a resource; it is the vital pulse of our ecological resilience and the primary determinant of our human vulnerability. Yet, in the high-stakes geopolitical landscape of South Asia, our rivers are increasingly being reconfigured from lifelines into instruments of hydro-coercion. As we stand at a historic junction, marked by the aftermath of the July 2024 revolution and the looming 2026 expiration of the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty, it is time to address the big picture of our water security. We must move beyond a legacy of downstream capitulation towards a future of water justice grounded in the recognition of our rivers as ecological commons.

The July 2024 uprising in Bangladesh did more than just overthrow a regime; it fundamentally altered the political foundations that had, for sixteen years, enabled India's hydro-coercive practices. Under the previous India-backed administration, Bangladesh often adopted a subservient posture in which domestic political legitimacy was essentially traded for Indian diplomatic patronage. This political accommodation created a dangerous feedback loop where our leadership avoided confronting treaty violations or upstream unilateralism in order to preserve broader bilateral ties. The revolution represented a conceivable rupture in this pattern of downstream capitulation. The popular uprising was fuelled by a deep-seated resentment against what many perceived as imperial control over domestic sovereignty, with water often serving as the primary tool of that control. Today, there is a burgeoning demand from the youth movement and civil society to decolonise our water governance and to challenge the colonial logics that have long normalised the advantage of upstream riparians at the expense of our survival.

To navigate this new era, we must understand what I have described as hydro-coercion, a strategic evolution of hydro-hegemony. While hydro-hegemony describes a general state of dominance in which a riparian state uses power to secure water objectives, hydro-coercion is the active weaponisation of water control for immediate and long-term political objectives. It functions as a mechanism of escalating spatial and geopolitical domination, where the upstream state exerts direct or indirect pressure on downstream states to force compliance. In the India–Bangladesh context, this power is deployed through three distinct but overlapping strategies that amount to a form of political colonisation.

The first of these is material hydro-coercion, which involves the physical control of water resources through large-scale infrastructure to reconfigure deltaic hydro-social territories. The Farakka Barrage is the most potent and enduring symbol of this material dominance. Commissioned in 1975 without meaningful consultation or consent from Bangladesh, the barrage unilaterally diverts dry-season flows. This infrastructure is not merely a technical solution for navigability but an enduring instrument of control that embeds hydro-insecurity into our national consciousness. By physically altering the flow of the Ganges, India uses its geographical advantage to impose a reality of scarcity upon the downstream delta, effectively redrawing the social and ecological map of the region to suit its own interests.

The Farakka Barrage in West Bengal stands as the primary site of upstream water control on the Ganges.

The second dimension is institutional hydro-coercion, which operates through procedural manipulation, bargaining power, and what can be described as institutional stalling. The prolonged stalemate over the Teesta River is a clear instance of this strategy. Although an agreement was nearly finalised in 2011, it has been blocked for over a decade by the state government of West Bengal. This subnational veto allows the Indian federal government to avoid accountability for diplomatic failure while implicitly using the unresolved issue as leverage. This manufactured scarcity is a deliberate strategic delay in which non-decision and silence are weaponised as forms of structural power. By keeping Bangladesh in a state of perpetual negotiation and vulnerability, India maintains an advantageous position that pressures our nation into broader strategic alignment.

The third pillar is ideational hydro-coercion, which utilises water nationalism and diplomatic signalling to shape narratives of sovereignty and development. Water is imbued with powerful nationalistic meanings, transforming it from a natural resource into a symbol of national identity that justifies unilateral extraction. India frames its upstream schemes as essential to its national progress, often characterising downstream claims as impediments to its sovereign prerogatives. This ideational control extends to overt diplomatic pressure; for example, recent reports indicate that Indian politicians have suggested the 1996 Ganges Treaty could be reconsidered if Bangladesh's foreign policy diverges from Indian interests. Such statements explicitly link vital water access to foreign policy compliance, using water as a tool of deterrence to prevent Bangladesh from pursuing strategic autonomy or closer ties with other regional powers.

Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) Basin

The consequences of these coercive practices are not abstract theories but lived realities of pervasive precarity for millions of Bangladeshis. The diversion of the Ganges has led to severe salinity intrusion in our coastal regions, devastating agricultural lands and compromising potable water sources. This ecological degradation directly threatens the Sundarbans, which is the world's largest mangrove forest and our primary defence against climate-induced cyclones. In the north, the lack of predictable flow from the Teesta has led to the collapse of traditional livelihoods in fishing and agriculture. These disruptions drive internal migration and displacement, as rural communities are forced to abandon their ancestral lands for the precarious life of urban slums. This displacement is a form of structural violence, where hegemonic control over water fuels the redrafting of the social fabric of our nation.

This structural inequality is reaching a breaking point due to the threat multiplier of climate change. We are entering an era of unprecedented hydro-variability, where Himalayan glaciers are projected to decline by up to 40 percent by 2100. For Bangladesh, this means a future of catastrophic monsoon floods followed by acute dry-season scarcity. Our existing agreements, particularly the 1996 Ganges Treaty, are tragically ill-equipped for this volatility. The treaty treats water as a divisible commodity to be quantified and allocated based on historical data rather than as a shared, interconnected ecological system. It lacks flexible mechanisms for climate adaptation, enforceable environmental flow regimes, or joint data-sharing platforms. As the treaty approaches its 2026 expiration, we must realise that a static agreement is no longer a tool of cooperation; in a climate-stressed world, it becomes another mechanism of control.

It is a mistake to view water justice as a zero-sum game, because from a strategic perspective, hydro-coercion is self-defeating for India. A water-stressed, ecologically fragile Bangladesh is a source of regional instability. The cascading effects of environmental degradation, including mass migration, state fragility, and economic shocks, do not respect national borders. Furthermore, the regional power dynamic is shifting, as China's aggressive dam-building on the upper Brahmaputra creates a cascading hierarchy in which India itself is vulnerable to upstream control. If India continues to adopt a coercive posture towards its downstream neighbour, it weakens its own moral and legal standing when challenging Chinese unilateralism. True regional stability requires cooperative precedents rather than coercive ones.

Beyond the immediate concerns of water flow, the health of the India–Bangladesh relationship is foundational to broader regional prosperity across the energy, trade, and transportation sectors. Bangladesh provides critical transit and transhipment facilities that connect India's northeastern states to its mainland, while India is a major source of the electricity and consumer goods that fuel our economy. These sectors are deeply interdependent, yet this interdependence is poisoned by the mistrust generated by hydro-coercion. When water is used as a diplomatic lever, it creates a climate of uncertainty that hinders long-term investment in regional connectivity and energy grids. For instance, the vision of a seamless South Asian power pool, where hydroelectricity from Nepal and Bhutan flows through India to Bangladesh, cannot be realised if the participating nations remain locked in hydro-political disputes. Stable, neighbourly relations are not a luxury but a prerequisite for the economic integration that could lift millions out of poverty across the entire basin.

The path forward requires a fundamental structural transformation in how we govern our transboundary waters. We must move beyond narrow, secretive bilateral negotiations towards comprehensive basin-wide governance. This means involving all riparian states, including Nepal, Bhutan, India, and China, in holistic planning for our shared river systems. Bangladesh's June 2025 entry into the UNECE Water Convention is a critical first step in this strategic pivot, anchoring our claims in international legal norms of equitable and reasonable utilisation. This multilateral shift provides a normative basis to challenge unilateral actions and assert our downstream rights in a way that bilateralism never could.

Transformative governance also necessitates the establishment of enforceable ecological safeguards. Future treaties must recognise the intrinsic value of water and include legally binding minimum environmental flow regimes to protect the health of our rivers and the biodiversity of the delta. Alongside these safeguards, we must demand drastic data transparency. The current information asymmetry is a tool of coercion, and we must insist on the mandatory, real-time sharing of hydrological and climate data. This is foundational for building trust, creating early warning systems, and ensuring collaborative management in an era of climate uncertainty. Most importantly, we must shift the discourse from water as a diplomatic concession to water as a fundamental human right. Access to water for basic needs, livelihoods, and ecological sustenance must be non-negotiable.

The upcoming expiration of the Ganges Treaty in 2026 is our most significant strategic inflection point. We cannot afford to passively await upstream goodwill while our rivers dwindle. We must use this moment to demand an epistemic rupture, which is a break from the colonial-era logic of extraction and control. The rivers of the Bengal Delta are an ecological commons and a shared heritage that demands collective stewardship rather than competitive exploitation. By centring the voices of downstream communities and grounding our governance in ecological justice and the principles of the ecological commons, we can turn our shared rivers into sources of regional strength.

For a deltaic nation like Bangladesh, achieving water justice is not merely a goal of foreign policy; it is the absolute prerequisite for our survival. Sustainable water governance cannot rest upon the political subordination of downstream populations. If we are to ensure a stable and prosperous South Asia, we must move towards a future where shared rivers foster genuine cooperation and resilience rather than remaining potent symbols of power imbalance and perennial conflict. Only by radically changing our approach to water and embracing the principles of joint basin stewardship can we hope to preserve the lifeblood of our delta for generations to come. An equitable water future is the only path towards the regional peace and human security that our people so urgently deserve.

Farhana Sultana, PhD, is Professor of Geography and the Environment at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, USA. Her research focuses on the intersections of water governance, climate justice, and international development, with particular attention to South Asia.