Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,236

- Likes

- 8,072

- Nation

- Axis Group

Economy at a critical point despite some stability

Bangladesh’s economy may have regained some stability in recent months, but it now stands at a critical point, with inflation, financial sector weaknesses, low investment, governance shortcomings and external risks emerging as major threats, according to a new government report.

Economy at a critical point despite some stability

Tackle threats now or risk slower growth, rising poverty, warns GED report

Bangladesh's economy may have regained some stability in recent months, but it now stands at a critical point, with inflation, financial sector weaknesses, low investment, governance shortcomings and external risks emerging as major threats, according to a new government report.

Unless these vulnerabilities are addressed, the country risks slower growth, falling living standards and rising poverty, warns the report, Bangladesh State of the Economy 2025, prepared by the General Economic Division (GED) of the Planning Commission.

"Foreign direct investment remains critically low and is expected to remain at this level in the coming months. Subdued investment and industrial activity are cited as major contributors to slower growth," states the report unveiled yesterday.

However, it added, "Bangladesh has a real chance to re-accelerate, build more resilient institutions, and make growth more inclusive.

"The key will be speed and seriousness of reform, clear communication, policy credibility, and ensuring that those reforms benefit ordinary people, not just aggregate macro statistics. Bangladesh has a real chance to re-accelerate."

The GED noted that the second half of fiscal year 2024-25 (FY25) showed rebounding economic activity. But the outlook remains clouded by political uncertainty, subdued industrial output, persistent inflation and global headwinds, including pressures linked to the reciprocal tariff imposed by the United States.

It pointed out that growth forecasts from international agencies, including the World Bank, now range between 3.3 percent and 4.1 percent for FY25, with a modest rebound expected in the ongoing fiscal year. According to provisional government data, the growth rate for FY25 stood at 3.97 percent.

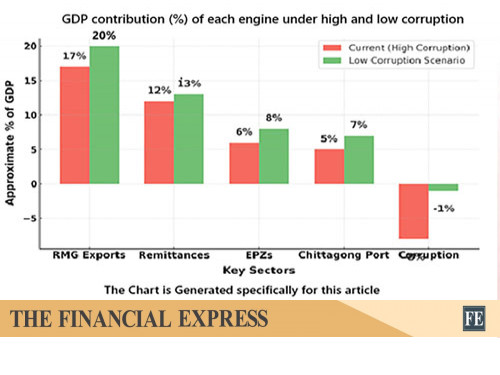

The GED identified remittances, export performance and manufacturing, particularly garments and SMEs, as the main drivers of growth in FY26, while noting that improvements in capital machinery imports may indicate early signs of recovering investment appetite.

The report, however, stresses that inflation continues to erode real incomes, particularly among low-income households.

"If Bangladesh can keep inflation under control, rebuild investor confidence, and stabilise the financial sector, there is potential for stronger growth in FY26."

Foreign exchange reserves stabilised at a level above three months of import coverage, it also said, attributing this to prudent macroeconomic management and structural strengthening of the economy's external front.

"A VICIOUS CYCLE"

Speaking at the event, Prof Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), recognised that some stability has returned but said it comes at a cost.

"The [existing] high policy rates being used to curb inflation really hurt investment. But interest is only one part of the cost of capital. Entrepreneurs face many other expenses as well," he said.

"We needed to ease the burden on entrepreneurs in these other areas, like strengthening institutional capacity and reducing corruption. We should have done more, especially since the cost of capital is already high. But we didn't," he added.

The economist said the lack of initiatives has trapped the economy in a "vicious cycle" of high interest rates increasing the cost of capital, which is raising the cost of doing business, and which ultimately depresses investment and job creation.

He warned that without faster reforms and stronger revenue mobilisation, Bangladesh risks slipping into a debt trap.

Former World Bank economist Zahid Hussain said the economy is sending mixed signals.

Remittances, slower illicit outflows, stronger revenue trends, steady electricity supply and natural-disaster resilience are positives, he said. But inflation, falling real wages, stagnant employment, weak export momentum and low investment paint a more worrying picture.

"Overall, the negative basket outweighs the positive," he said, noting that while the situation has not deteriorated as severely as feared, more decisive implementation of reforms could have produced stronger results.

"This government has shown ample evidence of intent to reform. But at the ground level, we still do not see major, visible results. To push reforms forward, willpower alone is not enough-stamina is also crucial," he added.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh Bank Governor Ahsan H Mansur stated that stabilising the financial sector remains difficult, even though the external sector is showing no major signs of stress.

He mentioned several reform initiatives taken by the interim government to stabilise the financial sector, including changes to the Bank Company Act, issuing the Bank Resolution Ordinance and restructuring the boards of several banks. "We also have to make the next government accountable for these things because these are significant progressions."

The governor said reserves have risen by about $10 billion over the past 16-17 months, and reiterated that the policy rate will not be lowered until inflation declines to a tolerable level.

Shafiqul Alam, chief adviser's press secretary, criticised sections of the business community and media for highlighting "only negative developments", failing to acknowledge reforms such as the Chattogam port modernisation drive.

"If the Chattogram port becomes efficient, the garment sector would benefit first," he said, adding that the government has not seen a single welcoming statement from the many top trade bodies.

National Board of Revenue (NBR) Chairman Md Abdur Rahman Khan said the tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen from over 10 percent a few years ago to around 7 percent now, as revenue cannot be collected from all sectors of the economy.

Speaking on Prof Rahman's warning about falling into a debt trap, he said, "We have already fallen into a debt trap; unless we acknowledge this truth, it will not be possible to move forward."

Meanwhile, speaking on the government's reform initiatives, Anisuzzaman Chowdhury, special assistant to the chief adviser, said there is no textbook for the sequence and speed of reforms.

"We must decide what comes first, what comes later, and how to balance them. Low-hanging fruit should be taken first, but sometimes distortions or internal balance issues prevent that," he said.

Tackle threats now or risk slower growth, rising poverty, warns GED report

Bangladesh's economy may have regained some stability in recent months, but it now stands at a critical point, with inflation, financial sector weaknesses, low investment, governance shortcomings and external risks emerging as major threats, according to a new government report.

Unless these vulnerabilities are addressed, the country risks slower growth, falling living standards and rising poverty, warns the report, Bangladesh State of the Economy 2025, prepared by the General Economic Division (GED) of the Planning Commission.

"Foreign direct investment remains critically low and is expected to remain at this level in the coming months. Subdued investment and industrial activity are cited as major contributors to slower growth," states the report unveiled yesterday.

However, it added, "Bangladesh has a real chance to re-accelerate, build more resilient institutions, and make growth more inclusive.

"The key will be speed and seriousness of reform, clear communication, policy credibility, and ensuring that those reforms benefit ordinary people, not just aggregate macro statistics. Bangladesh has a real chance to re-accelerate."

The GED noted that the second half of fiscal year 2024-25 (FY25) showed rebounding economic activity. But the outlook remains clouded by political uncertainty, subdued industrial output, persistent inflation and global headwinds, including pressures linked to the reciprocal tariff imposed by the United States.

It pointed out that growth forecasts from international agencies, including the World Bank, now range between 3.3 percent and 4.1 percent for FY25, with a modest rebound expected in the ongoing fiscal year. According to provisional government data, the growth rate for FY25 stood at 3.97 percent.

The GED identified remittances, export performance and manufacturing, particularly garments and SMEs, as the main drivers of growth in FY26, while noting that improvements in capital machinery imports may indicate early signs of recovering investment appetite.

The report, however, stresses that inflation continues to erode real incomes, particularly among low-income households.

"If Bangladesh can keep inflation under control, rebuild investor confidence, and stabilise the financial sector, there is potential for stronger growth in FY26."

Foreign exchange reserves stabilised at a level above three months of import coverage, it also said, attributing this to prudent macroeconomic management and structural strengthening of the economy's external front.

"A VICIOUS CYCLE"

Speaking at the event, Prof Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), recognised that some stability has returned but said it comes at a cost.

"The [existing] high policy rates being used to curb inflation really hurt investment. But interest is only one part of the cost of capital. Entrepreneurs face many other expenses as well," he said.

"We needed to ease the burden on entrepreneurs in these other areas, like strengthening institutional capacity and reducing corruption. We should have done more, especially since the cost of capital is already high. But we didn't," he added.

The economist said the lack of initiatives has trapped the economy in a "vicious cycle" of high interest rates increasing the cost of capital, which is raising the cost of doing business, and which ultimately depresses investment and job creation.

He warned that without faster reforms and stronger revenue mobilisation, Bangladesh risks slipping into a debt trap.

Former World Bank economist Zahid Hussain said the economy is sending mixed signals.

Remittances, slower illicit outflows, stronger revenue trends, steady electricity supply and natural-disaster resilience are positives, he said. But inflation, falling real wages, stagnant employment, weak export momentum and low investment paint a more worrying picture.

"Overall, the negative basket outweighs the positive," he said, noting that while the situation has not deteriorated as severely as feared, more decisive implementation of reforms could have produced stronger results.

"This government has shown ample evidence of intent to reform. But at the ground level, we still do not see major, visible results. To push reforms forward, willpower alone is not enough-stamina is also crucial," he added.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh Bank Governor Ahsan H Mansur stated that stabilising the financial sector remains difficult, even though the external sector is showing no major signs of stress.

He mentioned several reform initiatives taken by the interim government to stabilise the financial sector, including changes to the Bank Company Act, issuing the Bank Resolution Ordinance and restructuring the boards of several banks. "We also have to make the next government accountable for these things because these are significant progressions."

The governor said reserves have risen by about $10 billion over the past 16-17 months, and reiterated that the policy rate will not be lowered until inflation declines to a tolerable level.

Shafiqul Alam, chief adviser's press secretary, criticised sections of the business community and media for highlighting "only negative developments", failing to acknowledge reforms such as the Chattogam port modernisation drive.

"If the Chattogram port becomes efficient, the garment sector would benefit first," he said, adding that the government has not seen a single welcoming statement from the many top trade bodies.

National Board of Revenue (NBR) Chairman Md Abdur Rahman Khan said the tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen from over 10 percent a few years ago to around 7 percent now, as revenue cannot be collected from all sectors of the economy.

Speaking on Prof Rahman's warning about falling into a debt trap, he said, "We have already fallen into a debt trap; unless we acknowledge this truth, it will not be possible to move forward."

Meanwhile, speaking on the government's reform initiatives, Anisuzzaman Chowdhury, special assistant to the chief adviser, said there is no textbook for the sequence and speed of reforms.

"We must decide what comes first, what comes later, and how to balance them. Low-hanging fruit should be taken first, but sometimes distortions or internal balance issues prevent that," he said.