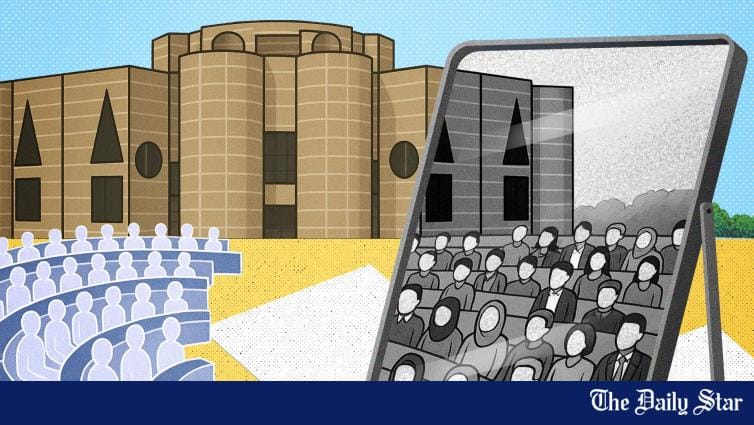

Election of proportional representation sparks concern of an AL comeback

Maruf Mullick

Published: 07 Jul 2025, 12: 26

One issue after another is being stirred up to obfuscate the issue of national election. Certain parties are trying to stall the election by coming up with all sorts of conditions. Unnecessary and irrelevant debates are being initiated. Unrealistic and unacceptable topics are being brought into discussion. One such issue is the proposal to implement a proportional representation system in the election. This has recently been raised at rallies held by Islamic parties as an alternative to the current constituency-based electoral system. Previously, Jamaat-e-Islami and the newly formed National Citizens Party (NCP) have also voiced support for this system at different times.

Their argument in favour of this demand is that it would help prevent authoritarianism by any future party, stop minority parties from forming governments, and ensure representation of all parties.

This system also raises the risk of extremist and separatist elements entering parliament. It encourages identity- or religion-based politics among voters. It can foster hardline nationalism

There are flaws in these arguments. The first flaw is that authoritarianism cannot be prevented simply by calculating votes. Regular elections are held in Iran, Turkey, and Russia. Western media have not reported major irregularities in their electoral processes. Yet, these countries have not been able to prevent authoritarian rule. Notably, in Turkey, the parliament is formed through a proportional party-list system, but the country has a presidential system of governance. So the parliament does not carry much weight. In Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is the ultimate authority, just as Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is in Iran, or Vladimir Putin in Russia.

Secondly, in a constituency-based system, it is not possible for a minority to form the government. For example, in 1991 BNP received 30.8 per cent of the vote and secured 140 seats. Awami League, on the other hand, got 30.1 per cent of the vote but only won 88 seats. Again, in the 2001 election, the BNP won 193 seats with 41 per cent of the vote, while the Awami League, with 40.1 per cent, managed to win only 62 seats. In this system, the country is divided into different electoral constituencies, giving importance to local preferences. A kind of decentralisation of opinion is evident here. That is why the party with the most seats forms the government.

It should be kept in mind that the call for proportional representation initially came from Awami League’s allies. In the 1990s, the Communist Party (CPB), a long-time ally of the Awami League, was the first to propose proportional seat allocation. Later, another Awami League ally, Jatiya Party, raised the issue. Since then, Awami League leaders themselves have also spoken in favour of it on various occasions. This can easily be verified on the Net.

Before the upcoming election, Jamaat-e-Islami, NCP and other Islamist parties have slipped into the shoes of Awami League and its allies. In both 1991 and 2001, Awami League received nearly as many votes as BNP but failed to form a government as it did not win enough seats. Meanwhile, Jamaat and other Islamist parties have never performed well in a constituency-based election on their own. In 1996, Jamaat contested independently and won only three seats. Islami Oikya Jote managed to win just one or two seats.

Their situation remains largely unchanged today. They haven’t gained enough public support to win a significant number of seats. As a new party, NCP also doesn’t appear to be in a promising position. They calculate that a proportional representation system would give them more seats in parliament. For instance, Jamaat’s best performance in a solo election yielded just three seats. Some may cite the 1991 election, but Jamaat’s 18-seat win that year was the result of an unofficial understanding with BNP. In that election, Jamaat’s former ameer, Matiur Rahman Nizami, won a seat in Pabna with 55,707 votes. But in the 1996 election, when Jamaat contested alone, he came in third.

In 2001, he won again through an alliance with BNP. This shows that he couldn’t win without an alliance. In the 1996 election, Jamaat received 8.61 per cent of the total vote. Under proportional seat allocation, that would have given them 27 seats in parliament. That means Matiur Rahman Nizami could have been an MP in 1996. Even Shafiqur Rahman, the current ameer of Jamaat, who has not done well in national elections, could have made it to parliament under such a system. This is the main reason Jamaat supports proportional representation. A few other parties, including NCP, have echoed this demand. Since these parties have low popularity, their chances of winning many seats under the constituency system are slim. That is why they are advocating proportional representation in the hope of gaining a few seats.

Although proportional representation claims to ensure representation for all parties, in practice not all of them make it to parliament. A certain vote threshold must be crossed to win seats. For instance, even in countries with mixed electoral systems like Germany, a party must receive at least 5 per cent of the vote to gain parliamentary representation. In some countries, the threshold is 7 per cent; in others, 2.5 per cent. This varies depending on the population, number of political parties, and the voter base.

The biggest flaw of the proportional system is that it does not elect direct representatives of the people. It elects parties to govern. Except for a few rare exceptions, most countries using this system assign representatives based on party lists. This increases the power of the party and its leadership. Only those individuals favoured by the party or its leader get a chance to enter parliament. In constituency-based systems, local popularity is often taken into account when selecting candidates. In proportional systems, that opportunity shrinks. Parties no longer prioritise the opinions of local voters. This leads to further centralisation of power and narrows the scope for voter agency and decision-making.

This system also raises the risk of extremist and separatist elements entering parliament. It encourages identity- or religion-based politics among voters. It can foster hardline nationalism. Election politics may divide a country along ethnic or communal lines. Separatist groups may gradually grow stronger. This can put national independence and sovereignty at risk.

Such a system is likely to result in weak and unstable governments. The government becomes hostage to various ethnic or communal factions. It is forced to compromise on unacceptable issues just to cling to power. This can lead to constitutional deadlock.

Proportional representation also reduces accountability to voters. As a result, MPs often disregard local issues. It creates distance between MPs and local constituents.

Beyond all this, voter interest in elections may decline. Only the most loyal party supporters will continue voting. Swing voters may lose interest in the process.

Considering these issues -- our political maturity, as well as economic and social contexts --proportional representation is not a suitable option. Whether for the Lower House or the Upper House, there is no scope to implement this system. Holding constituency-based elections for the Lower House and allocating proportional seats in the upper house would not fundamentally change the character of the state. It would only create unnecessary complications. When it comes to the nation’s security and stability, there is no room for compromise.

It’s not as simple as saying: “Let’s accept the demand and hand out a few Upper House seats to some parties.” Governing a state is no child’s play. It requires wisdom and sound judgment.

Now the question may arise as to why this system is being implemented in most European countries. The primary reason is that in most of these European countries, there are strong and autonomous local government systems in place at the provincial and municipal levels. These local governments are fully self-governed. They formulate their own development plans. Sectors such as health, education, transport, commerce, and even law enforcement fall under the jurisdiction of local governments.

The central government only sets laws and policies. It monitors whether the local governments are properly following those laws and policies. Only defence and foreign policy are fully handled by the central government. In all other areas, local governments can reject central decisions and make their own. Moreover, many of these countries follow presidential systems of government.

In our country, there is no such strong or autonomous local government system. Everything is governed and controlled by the central government. In such a situation, adopting a proportional representation system would lead to administrative disorder. The most concerning aspect is that if this system is implemented, the ousted Awami League could return to parliament under a different guise.

Taking everything into account, our country is in no way prepared for elections based on proportional representation. The application of such a system is not feasible here. It may still be imposed by force, but doing so would put the country at serious risk. Some small parties, in trying to advance their narrow self-interests, are endangering national security. They remain trapped within the bounds of narrow partisan politics. National security and stability do not appear to be their concern.

* Dr. Maruf Mallick is a political analyst