Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 17,618

- Likes

- 8,463

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Date of Event:

Jul 21, 2025

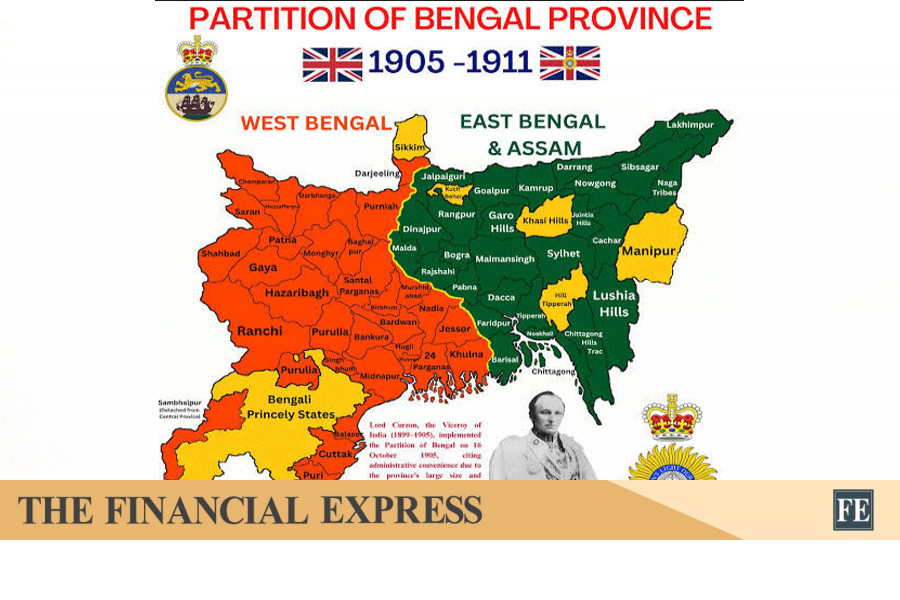

Bengal used to be the richest region of the world in the past. It had the most modern and largest textile industry in the whole world. Bengal used to have 23% of world's GDP. Today, Bangladesh is strategically important to the USA, China and India. But it has lost its rich economy due to exploitation by the British East India Company for almost 200 years. My question is, can the rich Bengal of the past be revived?

Last edited: