Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 15,828

- Likes

- 7,967

- Nation

- Axis Group

BGMEA seeks clarity on US raw material usage formula for duty waiver

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) on Wednesday sought clarification on the formula for calculating US raw material usage and mechanisms to ensure transparency and traceability throughout the supply chain to get the recently announced duty waiver on American raw

BGMEA seeks clarity on US raw material usage formula for duty waiver

FE Online Report

Published :

Aug 13, 2025 22:22

Updated :

Aug 13, 2025 22:22

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) on Wednesday sought clarification on the formula for calculating US raw material usage and mechanisms to ensure transparency and traceability throughout the supply chain to get the recently announced duty waiver on American raw materials usage.

It also discussed the possibility of establishing a warehouse near Chattogram Port to expedite cotton imports from the United States.

The requests were made when a delegation from the US Embassy in Dhaka met with BGMEA President Mahmud Hasan Khan at his BGMEA Complex office in Dhaka city, according to a statement.

The US Embassy delegation included Labour Attaché Leena Khan, Foreign Commercial Service Attaché Paul G Frost, Foreign Agricultural Service Attaché Erin Covert, and Economic Officer Richard Rasmussen. From BGMEA, Senior Vice President Inamul Haq Khan, Vice President Md Rezwan Selim, Vice President (Finance) Mijanur Rahman, Vice President Vidiya Amrit Khan, and Directors Mohammad Abdur Rahim, Faisal Samad, and Sheikh Hossain Muhammad Mustafiz attended the meeting.

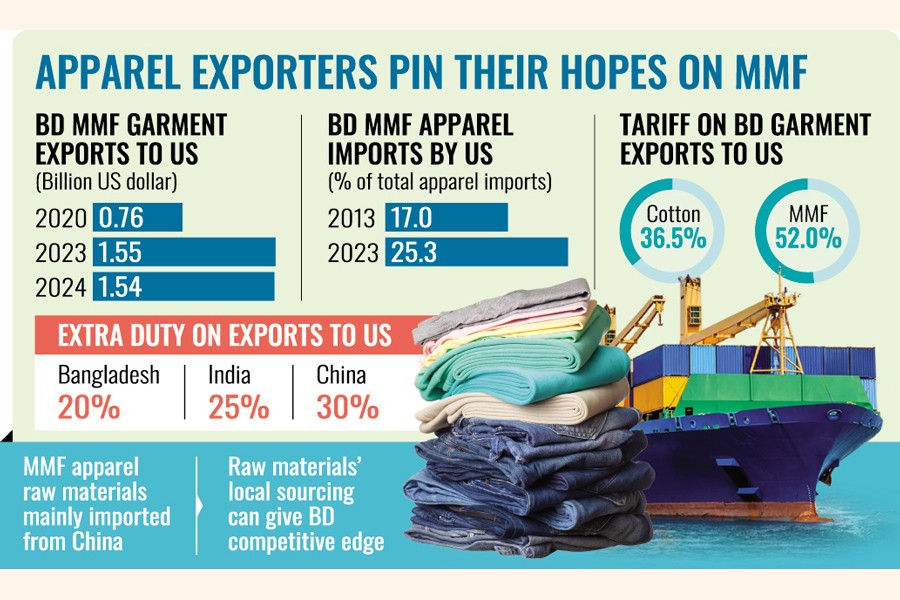

A key topic of the meeting was a recent US executive order that allows garments exported from Bangladesh to be proportionately exempt from a newly imposed additional 20 per cent duty, provided that at least 20 per cent of the raw materials used in these garments are sourced from the United States, the statement added.

Welcoming the initiative, BGMEA President Mahmud Hasan Khan said that the Bangladesh apparel industry is highly interested in utilising this facility.

The meeting also discussed the possibility of setting up the warehouse as a Bangladeshi initiative, a US initiative, or a joint venture, saying that it would help reduce lead time in the garment industry.

In addition to cotton, the BGMEA leaders expressed interest in importing man-made fiberes such as polyester and nylon from the United States (if produced by the US textile sector). They requested more detailed information on this from the US Embassy.

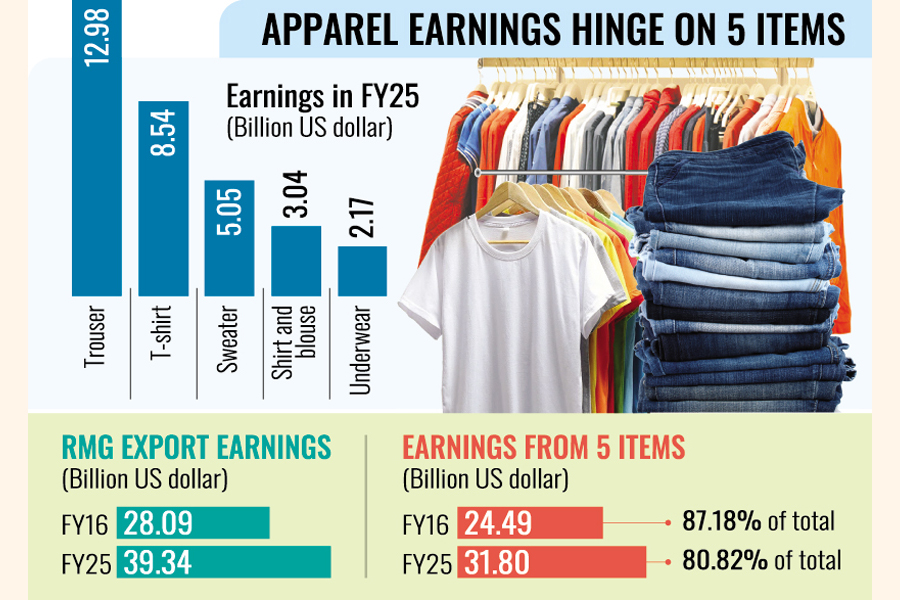

During the meeting, various issues of mutual interest were discussed, with a particular focus on strengthening bilateral trade relations between the United States and Bangladesh, centring around increasing exports of Bangladeshi ready-made garments (RMG) to the US market and enhancing overall economic cooperation.

In response, Foreign Commercial Service Attaché Paul G Frost said they would talk to relevant US government departments and provide further details.

The meeting also discussed potential collaboration between BGMEA and the US Cotton Council.

Paul G Frost mentioned that the embassy would discuss this with the US government's textile department and provide feedback to BGMEA.

Issues regarding the domestic gas and electricity situation were also discussed.

BGMEA leaders expressed hope that Bangladesh would be able to import LNG gas from the United States in the future. The issue of labour rights also received due attention during the meeting.

BGMEA President Mr Khan said that maintaining stable labour conditions in the garment sector is a top priority.

He informed the US delegation that since taking office, his board has engaged in dialogue with 81 workers' federations to establish harmonious industrial relations.

He also briefed the delegation on the progress of legal reforms aimed at ensuring labour rights and welfare.

The US delegation emphasised that aligning Bangladesh's labour laws with international standards is an international expectation, supported by the ILO, the European Union, and others.

BGMEA leaders stressed the importance of maintaining close communication with the US Embassy on labour-related matters to ensure clarity and avoid any misunderstandings.

The US side encouraged BGMEA to participate in SelectUSA, a major US investment promotion event scheduled to take place in May 2026, as an avenue to expand exports and build networks with American buyers.

Both parties expressed optimism about strengthening future economic partnerships and mutual cooperation between the two countries.

FE Online Report

Published :

Aug 13, 2025 22:22

Updated :

Aug 13, 2025 22:22

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) on Wednesday sought clarification on the formula for calculating US raw material usage and mechanisms to ensure transparency and traceability throughout the supply chain to get the recently announced duty waiver on American raw materials usage.

It also discussed the possibility of establishing a warehouse near Chattogram Port to expedite cotton imports from the United States.

The requests were made when a delegation from the US Embassy in Dhaka met with BGMEA President Mahmud Hasan Khan at his BGMEA Complex office in Dhaka city, according to a statement.

The US Embassy delegation included Labour Attaché Leena Khan, Foreign Commercial Service Attaché Paul G Frost, Foreign Agricultural Service Attaché Erin Covert, and Economic Officer Richard Rasmussen. From BGMEA, Senior Vice President Inamul Haq Khan, Vice President Md Rezwan Selim, Vice President (Finance) Mijanur Rahman, Vice President Vidiya Amrit Khan, and Directors Mohammad Abdur Rahim, Faisal Samad, and Sheikh Hossain Muhammad Mustafiz attended the meeting.

A key topic of the meeting was a recent US executive order that allows garments exported from Bangladesh to be proportionately exempt from a newly imposed additional 20 per cent duty, provided that at least 20 per cent of the raw materials used in these garments are sourced from the United States, the statement added.

Welcoming the initiative, BGMEA President Mahmud Hasan Khan said that the Bangladesh apparel industry is highly interested in utilising this facility.

The meeting also discussed the possibility of setting up the warehouse as a Bangladeshi initiative, a US initiative, or a joint venture, saying that it would help reduce lead time in the garment industry.

In addition to cotton, the BGMEA leaders expressed interest in importing man-made fiberes such as polyester and nylon from the United States (if produced by the US textile sector). They requested more detailed information on this from the US Embassy.

During the meeting, various issues of mutual interest were discussed, with a particular focus on strengthening bilateral trade relations between the United States and Bangladesh, centring around increasing exports of Bangladeshi ready-made garments (RMG) to the US market and enhancing overall economic cooperation.

In response, Foreign Commercial Service Attaché Paul G Frost said they would talk to relevant US government departments and provide further details.

The meeting also discussed potential collaboration between BGMEA and the US Cotton Council.

Paul G Frost mentioned that the embassy would discuss this with the US government's textile department and provide feedback to BGMEA.

Issues regarding the domestic gas and electricity situation were also discussed.

BGMEA leaders expressed hope that Bangladesh would be able to import LNG gas from the United States in the future. The issue of labour rights also received due attention during the meeting.

BGMEA President Mr Khan said that maintaining stable labour conditions in the garment sector is a top priority.

He informed the US delegation that since taking office, his board has engaged in dialogue with 81 workers' federations to establish harmonious industrial relations.

He also briefed the delegation on the progress of legal reforms aimed at ensuring labour rights and welfare.

The US delegation emphasised that aligning Bangladesh's labour laws with international standards is an international expectation, supported by the ILO, the European Union, and others.

BGMEA leaders stressed the importance of maintaining close communication with the US Embassy on labour-related matters to ensure clarity and avoid any misunderstandings.

The US side encouraged BGMEA to participate in SelectUSA, a major US investment promotion event scheduled to take place in May 2026, as an avenue to expand exports and build networks with American buyers.

Both parties expressed optimism about strengthening future economic partnerships and mutual cooperation between the two countries.