- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #16

Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 14,377

- Reaction score

- 7,589

- Origin

- Residence

- Axis Group

How social media became the frontline of the July Uprising

The July Movement in Bangladesh fused protest with digital defiance, using social media to bypass media silence, mobilize voices, and challenge power. It reshaped activism, highlighting social media’s role in truth, trauma, and transformation.

How social media became the frontline of the July Uprising

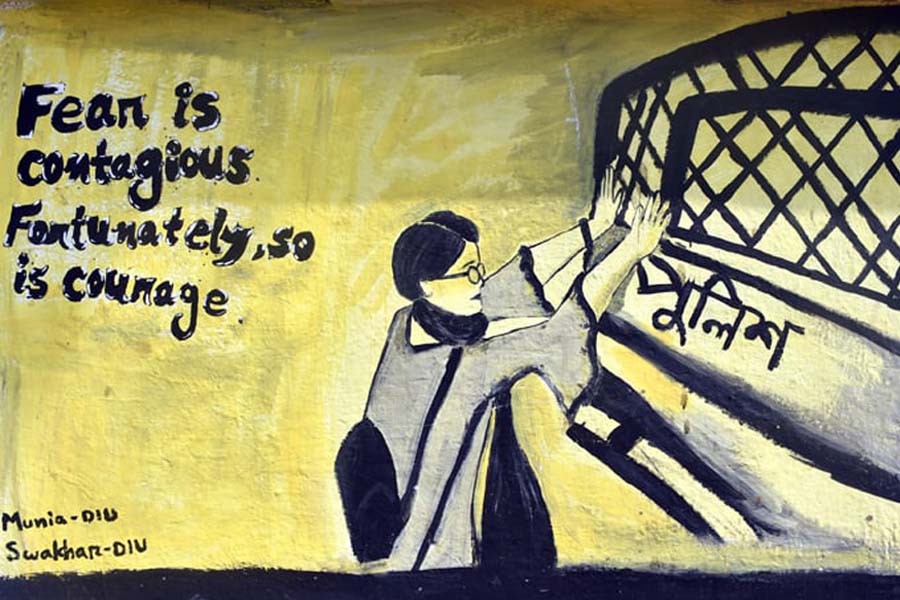

Image: LS

The July Movement did not start with a hashtag. It started with rage, grief, and a country cracking under pressure. However, it found its momentum online, mutating into a hybrid of protest and pixels, strategy and storytelling, bloodshed and bandwidth. When bullets hit the streets, stories hit the feeds. Before headlines could make sense of it, Instagram stories, Facebook lives, digital illustrations, and satirical memes did the job. And it was not the newsrooms that led this. It was a decentralised army of students, actors, presenters, illustrators, and people you would never have heard of, until they became the voice you could not ignore.

Manzur-al-Matin

A movement that could not be silenced

"Social media acted as a replacement for mainstream media," said Manzur-al-Matin, a lawyer, television host, and one of the familiar faces during the July mass uprising.

"Excluding a few newspapers, television in particular, was not showing anything. News of people dying was not coming out. There was a kind of media silencing… So, people became dependent on social media. It played a role both in mobilising and informing."

Matin recalled receiving tactical instructions via social media — how to treat tear gas wounds, how to regroup when scattered — "a tool for mass mobilisation," he called it. What made this different was that it did not rely on polished journalism. It relied on urgency, on participation, on people stepping up, logging in, and refusing to scroll past injustice.

Dipti Chowdhury, a TV presenter, also found herself at the centre of this shift. Her televised words, spoken during an internet shutdown, managed to go viral. She became, unwillingly, a symbol.

"That interview wasn't about me," she said. "It was everyone's experience of being silenced. People saw their own frustrations in my words.

"It's very difficult to control social media in a place where every person is like a TV channel. Even when the internet was shut down, VPNs kept the movement alive. People trusted social media more than conventional news."

Matin echoed the same. "We didn't speak up to go viral. We spoke up because staying silent felt like complicity. I tried to speak on TV. But after the 20th or 21st, that door closed. So, we took to the streets."

Dipti Chowdhury

Praise, backlash, and the algorithm

Praise came. Then the backlash. Then came the algorithmic silence.

"We saw how some who praised us started abusing us later," Matin added. "But we still spoke up, even when it was no longer popular. Because conscience doesn't follow trends."

Chowdhury experienced this backlash not as a political figure, but as a woman.

"My family's legacy of freedom fighters was questioned. Memes were made about me. My gender became ammunition," she said. "We united in July. But afterwards, we returned to what we know best – isolating people."

Both Chowdhury and Matin agreed: the hardest part was not speaking up during chaos. It was standing firm in the silence that followed.

The mob in the mirror

What came next was even messier: everyone claiming activism. Everyone claiming to speak for "the people." But at what point does advocacy turn into mob rule?

"Most people don't understand what activism truly is," Chowdhury said bluntly. "They're provoking, dividing, claiming moral authority without responsibility. We've confused activism with chaos."

Matin was more philosophical. "Hate spreads faster online. The algorithm rewards outrage. But what we see on social media does not always reflect who we are as a people."

And yet, both admit that digital spaces can no longer be dismissed as fluff. "Social media isn't just entertainment," Chowdhury emphasised. "It's political, it's economic, and it's dangerous when left unchecked."

Trauma, memory, and scrolling past grief

The digital aftermath is murky. The self-censorship that once ruled the internet is now replaced by a chaotic flood of unfiltered rage. But is that freedom – or another kind of trap?

Matin believes self-censorship still exists. "Just in different forms. Those who were once in power used to speak freely. Now, they censor themselves. And those who feel safe now speak recklessly. Social media gives voice to both truth and narcissism," he explains.

Chowdhury agreed but added nuance. "Yes, people post more freely now. But many also post for profit. Likes mean money. Satirical videos have become a business. So, where's the integrity?"

Perhaps, the deepest thread running through both voices is that of mental health. The digital battlefield leaves no one untouched.

"People witnessed real trauma," Matin said. "Violence, death, loss. But did they process it? No. They escaped to social media – only to be retraumatised."

He warns that "reels reduce thinking. Fake happiness makes us feel worse." Negativity spreads faster than truth. If we don't become aware of how these platforms shape us, we'll lose more than we realise.

The fight is not over

July did not end in July. Its aftershocks continue – online and offline. It was a movement not just of protests, but of digital defiance. It exposed both the power and the peril of social media in Bangladesh.

"Every phone became a newsroom," Chowdhury said. "Every person became a media outlet."

And in that chaos, some truths became undeniable: that storytelling is resistance. That silence can be louder than screams. And that even when the cameras are off, the algorithm keeps recording.

So, what's left now?

Maybe it's what Chowdhury suggests: "Social media should no longer be treated as a toy. It's a weapon, a tool, and a responsibility."

Or maybe it's what Matin reminds us: "Praise fades. Backlash fades. What remains is your own conscience. So, speak when you must. But also listen. And never confuse noise with clarity."

Chowdhury elaborates — "I was afraid. I didn't stay at home for days. I received threats saying if a certain party came to power, I'd be raped in the street or killed on sight. But I also received so much love. At one point, I thought — even if I'm jailed or killed, this much love is enough for a life."

As the dust settles, one thing remains clear: social media is no longer just a passive medium in Bangladesh. It is a force that can amplify movements, challenge silences, and reshape public consciousness. How this force is wielded in the future will continue to define the contours of resistance, representation, and responsibility in the digital age.

Photo: Collected

Image: LS

The July Movement did not start with a hashtag. It started with rage, grief, and a country cracking under pressure. However, it found its momentum online, mutating into a hybrid of protest and pixels, strategy and storytelling, bloodshed and bandwidth. When bullets hit the streets, stories hit the feeds. Before headlines could make sense of it, Instagram stories, Facebook lives, digital illustrations, and satirical memes did the job. And it was not the newsrooms that led this. It was a decentralised army of students, actors, presenters, illustrators, and people you would never have heard of, until they became the voice you could not ignore.

Manzur-al-Matin

A movement that could not be silenced

"Social media acted as a replacement for mainstream media," said Manzur-al-Matin, a lawyer, television host, and one of the familiar faces during the July mass uprising.

"Excluding a few newspapers, television in particular, was not showing anything. News of people dying was not coming out. There was a kind of media silencing… So, people became dependent on social media. It played a role both in mobilising and informing."

Matin recalled receiving tactical instructions via social media — how to treat tear gas wounds, how to regroup when scattered — "a tool for mass mobilisation," he called it. What made this different was that it did not rely on polished journalism. It relied on urgency, on participation, on people stepping up, logging in, and refusing to scroll past injustice.

Dipti Chowdhury, a TV presenter, also found herself at the centre of this shift. Her televised words, spoken during an internet shutdown, managed to go viral. She became, unwillingly, a symbol.

"That interview wasn't about me," she said. "It was everyone's experience of being silenced. People saw their own frustrations in my words.

"It's very difficult to control social media in a place where every person is like a TV channel. Even when the internet was shut down, VPNs kept the movement alive. People trusted social media more than conventional news."

Matin echoed the same. "We didn't speak up to go viral. We spoke up because staying silent felt like complicity. I tried to speak on TV. But after the 20th or 21st, that door closed. So, we took to the streets."

Dipti Chowdhury

Praise, backlash, and the algorithm

Praise came. Then the backlash. Then came the algorithmic silence.

"We saw how some who praised us started abusing us later," Matin added. "But we still spoke up, even when it was no longer popular. Because conscience doesn't follow trends."

Chowdhury experienced this backlash not as a political figure, but as a woman.

"My family's legacy of freedom fighters was questioned. Memes were made about me. My gender became ammunition," she said. "We united in July. But afterwards, we returned to what we know best – isolating people."

Both Chowdhury and Matin agreed: the hardest part was not speaking up during chaos. It was standing firm in the silence that followed.

The mob in the mirror

What came next was even messier: everyone claiming activism. Everyone claiming to speak for "the people." But at what point does advocacy turn into mob rule?

"Most people don't understand what activism truly is," Chowdhury said bluntly. "They're provoking, dividing, claiming moral authority without responsibility. We've confused activism with chaos."

Matin was more philosophical. "Hate spreads faster online. The algorithm rewards outrage. But what we see on social media does not always reflect who we are as a people."

And yet, both admit that digital spaces can no longer be dismissed as fluff. "Social media isn't just entertainment," Chowdhury emphasised. "It's political, it's economic, and it's dangerous when left unchecked."

Trauma, memory, and scrolling past grief

The digital aftermath is murky. The self-censorship that once ruled the internet is now replaced by a chaotic flood of unfiltered rage. But is that freedom – or another kind of trap?

Matin believes self-censorship still exists. "Just in different forms. Those who were once in power used to speak freely. Now, they censor themselves. And those who feel safe now speak recklessly. Social media gives voice to both truth and narcissism," he explains.

Chowdhury agreed but added nuance. "Yes, people post more freely now. But many also post for profit. Likes mean money. Satirical videos have become a business. So, where's the integrity?"

Perhaps, the deepest thread running through both voices is that of mental health. The digital battlefield leaves no one untouched.

"People witnessed real trauma," Matin said. "Violence, death, loss. But did they process it? No. They escaped to social media – only to be retraumatised."

He warns that "reels reduce thinking. Fake happiness makes us feel worse." Negativity spreads faster than truth. If we don't become aware of how these platforms shape us, we'll lose more than we realise.

The fight is not over

July did not end in July. Its aftershocks continue – online and offline. It was a movement not just of protests, but of digital defiance. It exposed both the power and the peril of social media in Bangladesh.

"Every phone became a newsroom," Chowdhury said. "Every person became a media outlet."

And in that chaos, some truths became undeniable: that storytelling is resistance. That silence can be louder than screams. And that even when the cameras are off, the algorithm keeps recording.

So, what's left now?

Maybe it's what Chowdhury suggests: "Social media should no longer be treated as a toy. It's a weapon, a tool, and a responsibility."

Or maybe it's what Matin reminds us: "Praise fades. Backlash fades. What remains is your own conscience. So, speak when you must. But also listen. And never confuse noise with clarity."

Chowdhury elaborates — "I was afraid. I didn't stay at home for days. I received threats saying if a certain party came to power, I'd be raped in the street or killed on sight. But I also received so much love. At one point, I thought — even if I'm jailed or killed, this much love is enough for a life."

As the dust settles, one thing remains clear: social media is no longer just a passive medium in Bangladesh. It is a force that can amplify movements, challenge silences, and reshape public consciousness. How this force is wielded in the future will continue to define the contours of resistance, representation, and responsibility in the digital age.

Photo: Collected