- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #41

Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 15,397

- Reaction score

- 7,865

- Points

- 209

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Renata wins EU nod for drug exports

Renata's export horizon will expand further as it has secured approval of the European Union months after an audit by European auditors of one of its production units. In a stock exchange filing on Wednesday, the listed drug maker disclosed that its Rajendrapur production unit had received Europea

Renata wins EU nod for drug exports

FE REPORT

Published :

Jul 17, 2025 09:53

Updated :

Jul 17, 2025 09:53

Renata's export horizon will expand further as it has secured approval of the European Union months after an audit by European auditors of one of its production units.

In a stock exchange filing on Wednesday, the listed drug maker disclosed that its Rajendrapur production unit had received European Union Good Manufacturing Practice (EU GMP) certification following a comprehensive audit by European authorities.

With that, Renata joins a small group of Bangladeshi pharma companies - Beximco Pharma, Incepta and Square Pharmaceutials -- that have EU GMP facilities.

Company officials said the certification had opened a door to the EU countries for exports of Renata's products.

Renata had already been exporting its products to the EU markets but on a limited scale in the absence of the certification. "Now, there is scope of getting approvals for a good number of our products by EU drug administrators," said Md. Jubayer Alam, company secretary of Renata.

The EU GMP certification confirms that the facility is compliant with strict European standards in manufacturing medicines, covering everything from hygiene, production, quality control, and documentation.

It is a mandatory requirement to export drugs to EU countries, which means Renata can now start expanding exports to Europe, adding a new revenue stream and increasing foreign exchange earnings for Bangladesh.

Conforming to the EU GMP usually involves significant investments in facilities, processes, and training. It pushes a company to improve its overall operational standards.

The same unit in Rajendrapur had secured access to the UK market and received approval of the US FDA, the world health organisation and the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency.

The EU auditors conducted the audit in February and the company received the certificate of GMP Compliance on Tuesday.

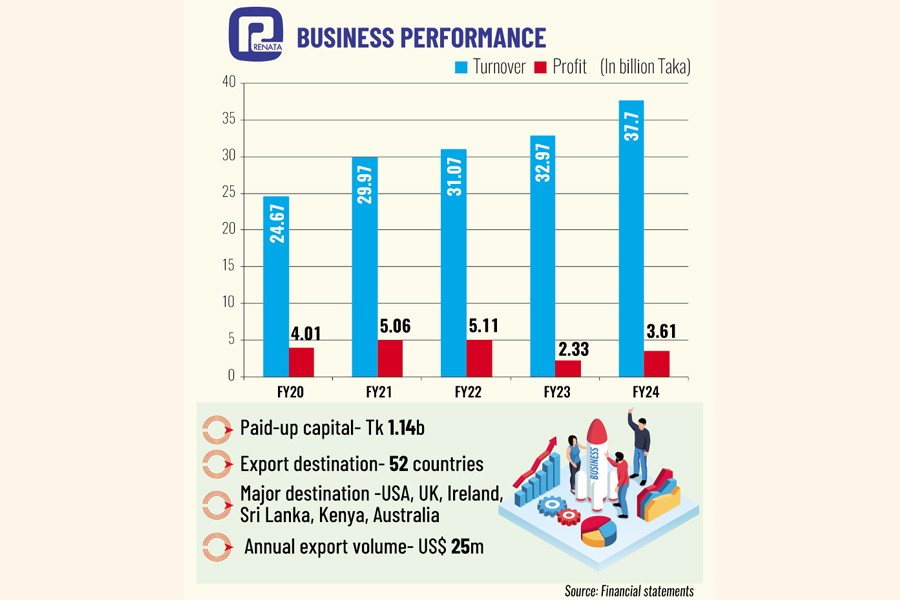

The annual export volume of Renata is around $25 million at present.

"The company's export volume will increase following our easy entry into the EU market," Mr Alam said.

The certification by the EU authorities is also accepted by the countries of Latin America.

"So, it will facilitate our exports to the markets of Latin America," Mr Alam added.

EU GMP is one of the most respected quality standards globally. It enhances Renata's credibility with global partners, investors, and regulatory authorities.

Therefore, the access to the EU may lead to new partnerships, higher stock valuations, and greater trust of institutional investors.

Meanwhile, investors appeared enthusiastic about bidding up shares of Renata as the stock price moved up 0.39 per cent to Tk 490.20 per share by the end of the trading session on the Dhaka Stock Exchange on Wednesday.

FE REPORT

Published :

Jul 17, 2025 09:53

Updated :

Jul 17, 2025 09:53

Renata's export horizon will expand further as it has secured approval of the European Union months after an audit by European auditors of one of its production units.

In a stock exchange filing on Wednesday, the listed drug maker disclosed that its Rajendrapur production unit had received European Union Good Manufacturing Practice (EU GMP) certification following a comprehensive audit by European authorities.

With that, Renata joins a small group of Bangladeshi pharma companies - Beximco Pharma, Incepta and Square Pharmaceutials -- that have EU GMP facilities.

Company officials said the certification had opened a door to the EU countries for exports of Renata's products.

Renata had already been exporting its products to the EU markets but on a limited scale in the absence of the certification. "Now, there is scope of getting approvals for a good number of our products by EU drug administrators," said Md. Jubayer Alam, company secretary of Renata.

The EU GMP certification confirms that the facility is compliant with strict European standards in manufacturing medicines, covering everything from hygiene, production, quality control, and documentation.

It is a mandatory requirement to export drugs to EU countries, which means Renata can now start expanding exports to Europe, adding a new revenue stream and increasing foreign exchange earnings for Bangladesh.

Conforming to the EU GMP usually involves significant investments in facilities, processes, and training. It pushes a company to improve its overall operational standards.

The same unit in Rajendrapur had secured access to the UK market and received approval of the US FDA, the world health organisation and the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency.

The EU auditors conducted the audit in February and the company received the certificate of GMP Compliance on Tuesday.

The annual export volume of Renata is around $25 million at present.

"The company's export volume will increase following our easy entry into the EU market," Mr Alam said.

The certification by the EU authorities is also accepted by the countries of Latin America.

"So, it will facilitate our exports to the markets of Latin America," Mr Alam added.

EU GMP is one of the most respected quality standards globally. It enhances Renata's credibility with global partners, investors, and regulatory authorities.

Therefore, the access to the EU may lead to new partnerships, higher stock valuations, and greater trust of institutional investors.

Meanwhile, investors appeared enthusiastic about bidding up shares of Renata as the stock price moved up 0.39 per cent to Tk 490.20 per share by the end of the trading session on the Dhaka Stock Exchange on Wednesday.