Lessons from Bangladesh

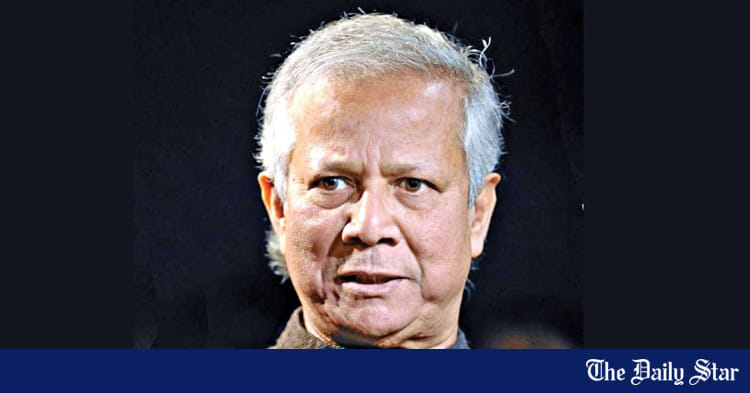

Photo: Prabir Das/Star/File

AFTER the tragic loss of an estimated 300 students during a fatal crackdown on protests in Bangladesh, the world stands captivated by the power of young students who led the demonstrations against Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed, the longest-serving prime minister of the country since its independence from Pakistan in 1971. She was forced to flee the country after over 15 years in power and a brutal campaign of weakening and persecuting any political opposition.

The issue arose with students' frustration at the inability to compete for lucrative government jobs, more than half of which were reserved under various quotas, the largest being the 30 per cent allocation for the children and grandchildren of those who fought for Bangladesh's independence.

This 30pc quota had been scrapped in 2018 after student protests, but the high court reinstated it in 2024 soon after Sheikh Hasina's fourth consecutive victory in a questionable election, widely cited as an unfair one.

When the students started demonstrating against the quota in order to gain their rightful share in taxpayer-funded government jobs on merit, the government and the students body linked with the ruling party responded violently, beating and killing students at Dhaka University. These protests spilled into the streets, transforming into an expression of frustration with the autocratic rule of the Awami League.

It should be encouraging that students in Bangladesh are taking a stand against nepotism.

It is being touted as the first revolution to be led by Gen-Z, the first digital native generation defined by its resolute no-nonsense attitude. Whereas understandably there is a lot of scepticism about whether this will lead to true democracy in Bangladesh — which will require a lot more than a series of demonstrations — it signals the approach of Gen-Z, which is shifting attitudes and practices in a post Covid-19 world as they enter the workforce. There are several lessons for the region and the world from the Bangladeshi Gen-Z's successful campaign against the Awami League government.

First, it shows the frustration that a lack of meritocracy in a state can lead to, especially when it has an economic impact. Universities in Bangladesh led the freedom movement in 1971 when the then East Pakistan was denied recognition of Bengali as an official language despite half the population speaking it. It should be encouraging that students are demanding merit and taking a stand against nepotism and favouritism-based quotas. States must ensure that public sector systems are fair.

Second, several commentators have pointed out that economic success in a country may not be enough to buy a population's acquiescence. Basic rights and equal distribution of resources are key for young people, the lack of which can lead to the toppling of a strong repressive government. Despite documented growth of above 8pc in Bangladesh, people were frustrated by the nepotism of and suppression by the regime, which resulted in unemployment among skilled youth. Assuming that economic prosperity in a pluralistic society will silence dissent is to fool oneself.

Third, censorship of the press and social media, and shutdown of internet and mobile phone networks are not effective in quelling protests and getting the word out in this day and age. Despite a countrywide internet shutdown in Bangladesh, the young protesters persisted and achieved what they had set out to do, all the while using various tools to get information out. It is prudent to listen to the voices of citizens, especially those who shape the nation and its future, rather than attempting to suppress them. Investment in digital repression is counterproductive and futile, especially when public funds that should be spent on progress and development are spent on stunting the potential of the digital economy. Nobody wants to do business with or hire talent from a country where internet shutdowns and the censorship of applications and websites are widespread and arbitrary. According to various estimates by watchdogs, internet shutdowns in Bangladesh cost the economy billions of dollars in the past month.

Fourth, the patriotism of the soldiers in Bangladesh must be appreciated. There is nothing more patriotic than refusing to fire at one's own citizens for demanding their rights, something everyone is entitled to do. Militaries must not turn against their own people as that is the job of occupiers, and not of one's own military that is sustained by the taxpayers. After all, the state belongs to its people and is built by them; orders to attack them must have no place in society.

Fifth, it is inevitable that people will rise against political persecution, illegitimate power grabbed through rigged elections, and a compromised judiciary. Political parties have more to gain by governing through legitimacy rather than relying on state machinery that engineers the usurping of legitimacy and undermining the will of the people.

Moving forward, the challenges for any decentralised youth-led change movement after initial success are two-fold. First, strategising to avoid being co-opted by local actors, such as the military or political parties, who can take advantage of the power vacuum for their own benefit. In such a situation, it is key for representatives of the students to insist on being a meaningful part of any process of change built on the blood and struggle of well-meaning youth.

Second, and the tougher one intrinsically linked to the self-serving cooperation of local power-brokers, is ensuring that the local struggle does not fall victim to the strategic games of international power-brokers who reject any local democratic processes, as was seen in Egypt in the aftermath of the Arab Spring protests. This should hold true even if the short-term objectives of the movement align with the foreign powers' objectives in the region. The US helped install dictator Gen Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt after helping him topple a democratically elected government led by Mohamed Morsi after 'Dictator-General' Hosni Mubarak was forced to step down by young protesters.

The power of a frustrated and informed young polity cannot be underestimated, and their struggle and idealism must not go to waste.

[The writer is director of Bolo Bhi, an advocacy forum for digital rights.]

Photo: Prabir Das/Star/File

AFTER the tragic loss of an estimated 300 students during a fatal crackdown on protests in Bangladesh, the world stands captivated by the power of young students who led the demonstrations against Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wajed, the longest-serving prime minister of the country since its independence from Pakistan in 1971. She was forced to flee the country after over 15 years in power and a brutal campaign of weakening and persecuting any political opposition.

The issue arose with students' frustration at the inability to compete for lucrative government jobs, more than half of which were reserved under various quotas, the largest being the 30 per cent allocation for the children and grandchildren of those who fought for Bangladesh's independence.

This 30pc quota had been scrapped in 2018 after student protests, but the high court reinstated it in 2024 soon after Sheikh Hasina's fourth consecutive victory in a questionable election, widely cited as an unfair one.

When the students started demonstrating against the quota in order to gain their rightful share in taxpayer-funded government jobs on merit, the government and the students body linked with the ruling party responded violently, beating and killing students at Dhaka University. These protests spilled into the streets, transforming into an expression of frustration with the autocratic rule of the Awami League.

It should be encouraging that students in Bangladesh are taking a stand against nepotism.

It is being touted as the first revolution to be led by Gen-Z, the first digital native generation defined by its resolute no-nonsense attitude. Whereas understandably there is a lot of scepticism about whether this will lead to true democracy in Bangladesh — which will require a lot more than a series of demonstrations — it signals the approach of Gen-Z, which is shifting attitudes and practices in a post Covid-19 world as they enter the workforce. There are several lessons for the region and the world from the Bangladeshi Gen-Z's successful campaign against the Awami League government.

First, it shows the frustration that a lack of meritocracy in a state can lead to, especially when it has an economic impact. Universities in Bangladesh led the freedom movement in 1971 when the then East Pakistan was denied recognition of Bengali as an official language despite half the population speaking it. It should be encouraging that students are demanding merit and taking a stand against nepotism and favouritism-based quotas. States must ensure that public sector systems are fair.

Second, several commentators have pointed out that economic success in a country may not be enough to buy a population's acquiescence. Basic rights and equal distribution of resources are key for young people, the lack of which can lead to the toppling of a strong repressive government. Despite documented growth of above 8pc in Bangladesh, people were frustrated by the nepotism of and suppression by the regime, which resulted in unemployment among skilled youth. Assuming that economic prosperity in a pluralistic society will silence dissent is to fool oneself.

Third, censorship of the press and social media, and shutdown of internet and mobile phone networks are not effective in quelling protests and getting the word out in this day and age. Despite a countrywide internet shutdown in Bangladesh, the young protesters persisted and achieved what they had set out to do, all the while using various tools to get information out. It is prudent to listen to the voices of citizens, especially those who shape the nation and its future, rather than attempting to suppress them. Investment in digital repression is counterproductive and futile, especially when public funds that should be spent on progress and development are spent on stunting the potential of the digital economy. Nobody wants to do business with or hire talent from a country where internet shutdowns and the censorship of applications and websites are widespread and arbitrary. According to various estimates by watchdogs, internet shutdowns in Bangladesh cost the economy billions of dollars in the past month.

Fourth, the patriotism of the soldiers in Bangladesh must be appreciated. There is nothing more patriotic than refusing to fire at one's own citizens for demanding their rights, something everyone is entitled to do. Militaries must not turn against their own people as that is the job of occupiers, and not of one's own military that is sustained by the taxpayers. After all, the state belongs to its people and is built by them; orders to attack them must have no place in society.

Fifth, it is inevitable that people will rise against political persecution, illegitimate power grabbed through rigged elections, and a compromised judiciary. Political parties have more to gain by governing through legitimacy rather than relying on state machinery that engineers the usurping of legitimacy and undermining the will of the people.

Moving forward, the challenges for any decentralised youth-led change movement after initial success are two-fold. First, strategising to avoid being co-opted by local actors, such as the military or political parties, who can take advantage of the power vacuum for their own benefit. In such a situation, it is key for representatives of the students to insist on being a meaningful part of any process of change built on the blood and struggle of well-meaning youth.

Second, and the tougher one intrinsically linked to the self-serving cooperation of local power-brokers, is ensuring that the local struggle does not fall victim to the strategic games of international power-brokers who reject any local democratic processes, as was seen in Egypt in the aftermath of the Arab Spring protests. This should hold true even if the short-term objectives of the movement align with the foreign powers' objectives in the region. The US helped install dictator Gen Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt after helping him topple a democratically elected government led by Mohamed Morsi after 'Dictator-General' Hosni Mubarak was forced to step down by young protesters.

The power of a frustrated and informed young polity cannot be underestimated, and their struggle and idealism must not go to waste.

[The writer is director of Bolo Bhi, an advocacy forum for digital rights.]