Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,880

- Likes

- 8,153

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Rohingyas detail worsening violence in Myanmar

Rohingya refugee Syed fled Myanmar for a second time last month, after he was forced to fight alongside the military that drove his family out of their homeland years earlier...

www.newagebd.net

www.newagebd.net

Rohingyas detail worsening violence in Myanmar

Agence France-Presse . Cox’s Bazar 24 September, 2024, 00:13

Rohingya refugee Syed fled Myanmar for a second time last month, after he was forced to fight alongside the military that drove his family out of their homeland years earlier.

Syed, whose name has been changed to protect him from reprisals, is one of thousands of young men from the stateless and persecuted Muslim minority rounded up to wage a war not of their own making.

Their conscription into the ranks of junta-run Myanmar’s military has prompted revenge attacks against civilians and pushed thousands more into Bangladesh, already host to around a million Rohingya refugees.

‘The people there are suffering a lot. I saw that with my own eyes,’ Syed said, soon after his escape and return to the squalid Bangladeshi relief camp he has called home for the past seven years.

‘Some are starving, they are dying of hunger,’ the 23-year-old added. ‘Everyone else is busy trying to save their own lives.’

Syed said he was conscripted by a Rohingya armed group operating in the camps in June and sent to fight against the Arakan Army, a rebel group waging war against Myanmar’s junta to carve out its own autonomous homeland.

He and other Rohingya recruits were put to work as porters, digging ditches and fetching water for Myanmar troops as they bunkered in against advancing rebel troops.

‘They didn’t give us any training,’ he said. ‘The military stay in the police stations, they don’t go out.’

Sent on patrol to a Muslim village, Syed was able to give his captors the slip and cross back over into Bangladesh.

He is one of around 14,000 Rohingya to have made the crossing in recent months as the fighting near the border has escalated, according to figures given by the UN refugee agency to the Bangladeshi government.

Experts say that at least 2,000 Rohingya have been forcibly recruited from refugee camps in Bangldesh this year, along with many more Rohingya living in Myanmar who were also conscripted.

Those pressed into service in Bangladesh say they were forced to do so by armed groups, apparently in return for concessions by Myanmar’s junta that could allow them to return to their homelands.

Both the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, the two armed groups operating in the camps, have denied conscripting refugees.

‘We had never forcefully recruited anyone for us or others,’ senior RSO leader Ko Ko Linn said.

The UN Human Rights Office said it had information that the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army had both committed serious abuses against the Rohingya during the conflict.

Other rights groups say that the press-ganging of Rohingya into service alongside Myanmar troops has fuelled retaliatory attacks by the Arakan Army.

In the worst documented instance, watchdog Fortify Rights said last month that the rebel group had killed more than 100 Rohingya men, women and children in a drone and mortar bombardment on the border.

The Arakan Army has repeatedly denied responsibility for the attack and accusations of targeting Rohingya civilians in general.

But many of the thousands of new refugees crossing into Bangladesh accuse the group of killings.

Mohammad Johar, 22, said that his brother-in-law was killed in a drone attack he blamed on the Arakan Army while the pair were fleeing the border town of Maungdaw earlier this month.

‘Dead bodies were lying everywhere, dead bodies were on the banks of the river,’ he said.

‘The Arakan Army is more powerful there. The Myanmar military can’t keep up with the Arakan Army. And they both bomb each other, but it’s the Muslims who are dying.’

Bangladesh has struggled for years to accommodate its immense population of refugees, most of whom arrived after a 2017 military crackdown in Myanmar which is the subject of an on-going UN genocide investigation.

Still reeling from the sudden overthrow of its previous government by a student-led revolution last month, Bangladesh says the new arrivals are not welcome.

‘We are sorry to say this, but it’s beyond our capacity to give shelter to anyone else,’ interim foreign minister Touhid Hossain said this month.

But after deadly attacks on some of the estimated 6,00,000 Rohingya still living in Myanmmar, the new arrivals said they had no choice but to seek safety across the border.

‘After seeing dead bodies, we were scared that more attacks were coming,’ 20-year-old Bibi Faiza said after crossing the border with her young daughter.

‘I don’t hear gunshots any more, and there is peace here.’

Agence France-Presse . Cox’s Bazar 24 September, 2024, 00:13

Rohingya refugee Syed fled Myanmar for a second time last month, after he was forced to fight alongside the military that drove his family out of their homeland years earlier.

Syed, whose name has been changed to protect him from reprisals, is one of thousands of young men from the stateless and persecuted Muslim minority rounded up to wage a war not of their own making.

Their conscription into the ranks of junta-run Myanmar’s military has prompted revenge attacks against civilians and pushed thousands more into Bangladesh, already host to around a million Rohingya refugees.

‘The people there are suffering a lot. I saw that with my own eyes,’ Syed said, soon after his escape and return to the squalid Bangladeshi relief camp he has called home for the past seven years.

‘Some are starving, they are dying of hunger,’ the 23-year-old added. ‘Everyone else is busy trying to save their own lives.’

Syed said he was conscripted by a Rohingya armed group operating in the camps in June and sent to fight against the Arakan Army, a rebel group waging war against Myanmar’s junta to carve out its own autonomous homeland.

He and other Rohingya recruits were put to work as porters, digging ditches and fetching water for Myanmar troops as they bunkered in against advancing rebel troops.

‘They didn’t give us any training,’ he said. ‘The military stay in the police stations, they don’t go out.’

Sent on patrol to a Muslim village, Syed was able to give his captors the slip and cross back over into Bangladesh.

He is one of around 14,000 Rohingya to have made the crossing in recent months as the fighting near the border has escalated, according to figures given by the UN refugee agency to the Bangladeshi government.

Experts say that at least 2,000 Rohingya have been forcibly recruited from refugee camps in Bangldesh this year, along with many more Rohingya living in Myanmar who were also conscripted.

Those pressed into service in Bangladesh say they were forced to do so by armed groups, apparently in return for concessions by Myanmar’s junta that could allow them to return to their homelands.

Both the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, the two armed groups operating in the camps, have denied conscripting refugees.

‘We had never forcefully recruited anyone for us or others,’ senior RSO leader Ko Ko Linn said.

The UN Human Rights Office said it had information that the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army had both committed serious abuses against the Rohingya during the conflict.

Other rights groups say that the press-ganging of Rohingya into service alongside Myanmar troops has fuelled retaliatory attacks by the Arakan Army.

In the worst documented instance, watchdog Fortify Rights said last month that the rebel group had killed more than 100 Rohingya men, women and children in a drone and mortar bombardment on the border.

The Arakan Army has repeatedly denied responsibility for the attack and accusations of targeting Rohingya civilians in general.

But many of the thousands of new refugees crossing into Bangladesh accuse the group of killings.

Mohammad Johar, 22, said that his brother-in-law was killed in a drone attack he blamed on the Arakan Army while the pair were fleeing the border town of Maungdaw earlier this month.

‘Dead bodies were lying everywhere, dead bodies were on the banks of the river,’ he said.

‘The Arakan Army is more powerful there. The Myanmar military can’t keep up with the Arakan Army. And they both bomb each other, but it’s the Muslims who are dying.’

Bangladesh has struggled for years to accommodate its immense population of refugees, most of whom arrived after a 2017 military crackdown in Myanmar which is the subject of an on-going UN genocide investigation.

Still reeling from the sudden overthrow of its previous government by a student-led revolution last month, Bangladesh says the new arrivals are not welcome.

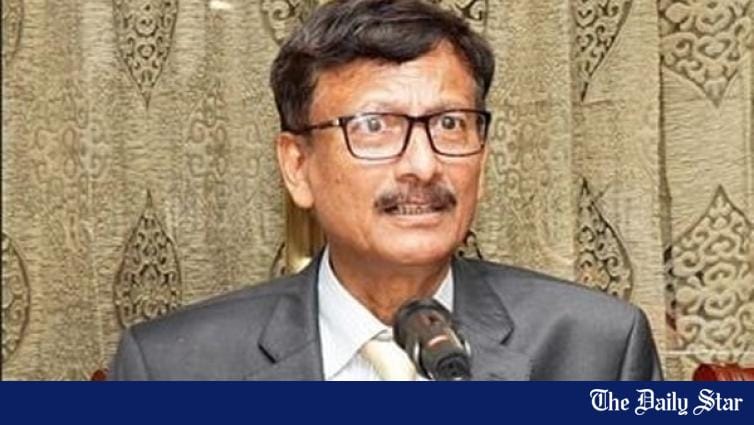

‘We are sorry to say this, but it’s beyond our capacity to give shelter to anyone else,’ interim foreign minister Touhid Hossain said this month.

But after deadly attacks on some of the estimated 6,00,000 Rohingya still living in Myanmmar, the new arrivals said they had no choice but to seek safety across the border.

‘After seeing dead bodies, we were scared that more attacks were coming,’ 20-year-old Bibi Faiza said after crossing the border with her young daughter.

‘I don’t hear gunshots any more, and there is peace here.’