Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,447

- Likes

- 8,111

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Skill training for local youths in areas hosting Rohingya

Undeniably, being the host to over one million Rohingya population displaced from their homeland in Myanmar, the Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas of Cox's Bazar are the most environmentally and socially challenged areas of Bangladesh. As reports go, environmentally, the localities where the Rohingya refug

Skill training for local youths in areas hosting Rohingya

FE

Published :

Dec 19, 2025 22:27

Updated :

Dec 19, 2025 22:27

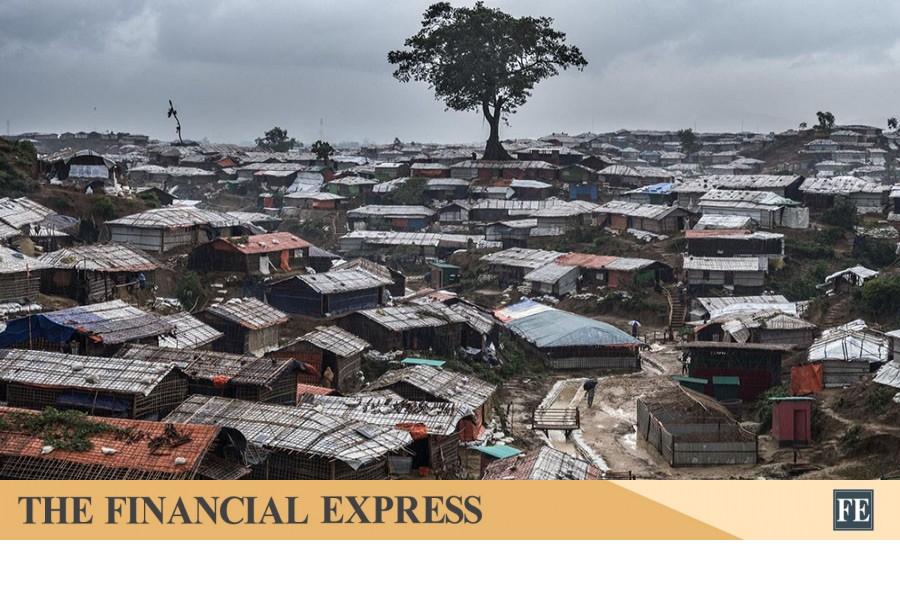

Undeniably, being the host to over one million Rohingya population displaced from their homeland in Myanmar, the Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas of Cox's Bazar are the most environmentally and socially challenged areas of Bangladesh. As reports go, environmentally, the localities where the Rohingya refugees are concentrated are marked by massive deforestation, biodiversity loss and water contamination. As a result, the local infrastructure has been strained. Socially, with massive increase in population, there have been severe labour market disruptions. Entry of such a large number of homeless people from across the border also means abundant cheap labour, which has significantly reduced income and employment opportunities of local day labourers and fishermen. Essential commodity prices and transportation costs have also risen markedly due to enhanced demand on the available supplies and services. This has led to social tension and, eventually, negative attitude towards the Rohingya refugees. Needless to say, these issues demand urgent addressing. Evidently, worse affected are the youth of the local communities who due to lack of employment opportunities are turning to drug addiction, crime and other anti-social activities. In this situation, alongside continuing the humanitarian services being extended to the Rohingya refugees, one cannot also be oblivious of the local communities, especially their youth members.

Against this backdrop, the youth and sports ministry of the government is learnt to have proposed two skill-development projects worth Tk 2.39 billion for youths from the local communities hosting Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar and across the Chattogram division. Notably, the financing of the project is reportedly coming from New Development Bank (NDB) of the BRICS countries. It is worthwhile to note that the BRICS is a major inter-governmental organization and economic bloc comprising emerging economies including 10 core members so far, namely, Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, UAE and Indonesia representing nearly 40 per cent of the world's GDP. Formerly known as BRICS Development Bank, NDB is a multilateral financial institution. This multilateral bank is supporting the youth development projects for Cox's Bazar and Chattogram division that aims to generate employment in the areas as noted in the foregoing. The project is supposed to benefit some 30,000 unemployed youths seriously affected by, as the project document terms, the Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs). Scheduled to start next year, 75 per cent of the allocation for Cox's Bazar part of the proposed youth employment project will go to train over 12,000 youths. Of the proposed skill development and employment generation project for Chattogram division, 93 per cent is learnt to be earmarked for training 20,000 youths.

As understood, the training activities on skill development would also involve awareness raising against drug abuse and human trafficking, which are admittedly the worst forms of degeneration and crimes destabilising the local communities. The varieties of trades to be covered by the said youth skill development and employment generation programme are no doubt impressive. Some of the activities to come under training, as mentioned in the report, include agro-processing and marketing, fisheries, tourism-related services, freelancing and basic technical skills etc. Once the project is implemented, hopefully it would open up wide opportunities of livelihoods for local youths and their families. And inclusion of sports-related activities would definitely help develop the local youths' physical and mental health.

The fact that the project tailor-made for Chattogram is aligned with the existing skill development agenda under the National Youth Policy 2017 is inspiring as it would obviously help reduce the number of youths Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET). Hopefully, the envisaged youth training and employment project would be able to fulfil its stated objectives. However, the government needs also to work harder to repatriate the Rohingya to their homeland.

FE

Published :

Dec 19, 2025 22:27

Updated :

Dec 19, 2025 22:27

Undeniably, being the host to over one million Rohingya population displaced from their homeland in Myanmar, the Ukhia and Teknaf upazilas of Cox's Bazar are the most environmentally and socially challenged areas of Bangladesh. As reports go, environmentally, the localities where the Rohingya refugees are concentrated are marked by massive deforestation, biodiversity loss and water contamination. As a result, the local infrastructure has been strained. Socially, with massive increase in population, there have been severe labour market disruptions. Entry of such a large number of homeless people from across the border also means abundant cheap labour, which has significantly reduced income and employment opportunities of local day labourers and fishermen. Essential commodity prices and transportation costs have also risen markedly due to enhanced demand on the available supplies and services. This has led to social tension and, eventually, negative attitude towards the Rohingya refugees. Needless to say, these issues demand urgent addressing. Evidently, worse affected are the youth of the local communities who due to lack of employment opportunities are turning to drug addiction, crime and other anti-social activities. In this situation, alongside continuing the humanitarian services being extended to the Rohingya refugees, one cannot also be oblivious of the local communities, especially their youth members.

Against this backdrop, the youth and sports ministry of the government is learnt to have proposed two skill-development projects worth Tk 2.39 billion for youths from the local communities hosting Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar and across the Chattogram division. Notably, the financing of the project is reportedly coming from New Development Bank (NDB) of the BRICS countries. It is worthwhile to note that the BRICS is a major inter-governmental organization and economic bloc comprising emerging economies including 10 core members so far, namely, Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, UAE and Indonesia representing nearly 40 per cent of the world's GDP. Formerly known as BRICS Development Bank, NDB is a multilateral financial institution. This multilateral bank is supporting the youth development projects for Cox's Bazar and Chattogram division that aims to generate employment in the areas as noted in the foregoing. The project is supposed to benefit some 30,000 unemployed youths seriously affected by, as the project document terms, the Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs). Scheduled to start next year, 75 per cent of the allocation for Cox's Bazar part of the proposed youth employment project will go to train over 12,000 youths. Of the proposed skill development and employment generation project for Chattogram division, 93 per cent is learnt to be earmarked for training 20,000 youths.

As understood, the training activities on skill development would also involve awareness raising against drug abuse and human trafficking, which are admittedly the worst forms of degeneration and crimes destabilising the local communities. The varieties of trades to be covered by the said youth skill development and employment generation programme are no doubt impressive. Some of the activities to come under training, as mentioned in the report, include agro-processing and marketing, fisheries, tourism-related services, freelancing and basic technical skills etc. Once the project is implemented, hopefully it would open up wide opportunities of livelihoods for local youths and their families. And inclusion of sports-related activities would definitely help develop the local youths' physical and mental health.

The fact that the project tailor-made for Chattogram is aligned with the existing skill development agenda under the National Youth Policy 2017 is inspiring as it would obviously help reduce the number of youths Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET). Hopefully, the envisaged youth training and employment project would be able to fulfil its stated objectives. However, the government needs also to work harder to repatriate the Rohingya to their homeland.