Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 15,397

- Nation

- Axis Group

TDS: How did you become involved with Tajuddin during the war?

MH: At that time, a Punjabi man named Jafar Naqvi lived next to my house. He had served as the Chief Reporter of The Pakistan Times between 1962 and 1964. We became very close friends. Both of us belonged to the same faction of the Communist Party — the one entangled in the Moscow–China ideological conflict. Like me, he was disillusioned with both sides, though he leaned more towards the pro-Moscow position. I was around 35 years old then, while he was over 40. By that time, he had left journalism and was serving as the resident director of Eastern Refinery Ltd in Chittagong. He frequently travelled between Chittagong and Karachi, as his maternal uncle was the head of the organisation.

Every week, he was required to report to Tikka Khan two to three times regarding Petroleum, Oil, and Lubricants — detailing available stock, goods in transit, and quantities being refined.

He would occasionally drop by and share updates. One day, he suddenly asked, "So, you're still around?" I replied, "Yes, everything seems normal now." He responded, "What normal? Another major crisis is imminent. It's going to happen soon."

He warned, "The Indians are training so many people — do you think Pakistan will just sit idle? They will strike. And once the attack happens, the war will begin."

He advised me to leave, saying, "War is about to begin again." When I asked why, he explained that the Pakistani army was delaying because the Chinese hadn't fully given their nod yet. Pakistan, he said, would find it difficult to go to war alone without clear support from China.

Within our group, we quietly gathered information. Shahidullah Kaiser, my mentor in the Communist Party, was a small-built, cheerful man of about 45. We met almost daily in Dhanmondi, where he, Ahmadul Kabir, and Zohur Hossain Chowdhury would often exchange news.

It was Shahidullah Kaiser who first told me that Tajuddin Ahmad was either in Kolkata or Delhi, and that I should go and find him — someone reliable was needed to brief them on the situation in Dhaka. So, in May, I went to Calcutta. I didn't find Tajuddin right away, but I met Amirul Islam and Nurul Quader first.

Tajuddin Ahmad first shared with me his belief that Mrs Gandhi was a sincere leader who would stand by Bangladesh's cause. In response, I raised a concern — though she may have assured full support, there remained a possibility that if China were to intervene or launch an attack, she might frame it as an external conflict and withdraw her support, leaving us to face the situation alone. This concern stemmed from insights I had received earlier from Jafar Naqvi.

Tajuddin acknowledged the risk but noted that such developments were beyond what they could have anticipated at the time.

I then argued that India's security could only be ensured through a firm assurance from the Soviet Union — specifically, that the Soviets would deter any potential Chinese aggression. I reminded him that China still had around one lakh soldiers deployed along the Ussuri River, and there was fighting between these two countries along the border. If China were to intervene and the Soviet Union formed a formal alliance with India, it could dissuade Chinese action. Only under such an arrangement, I asserted, could India feel genuinely secure. At that point, we had no other support on the global stage.

Tajuddin remained silent for a while and then suggested that I go to Delhi to raise these strategic concerns with Indian policymakers. Following his advice, I went to Delhi to engage with Indian policy-level think tanks.

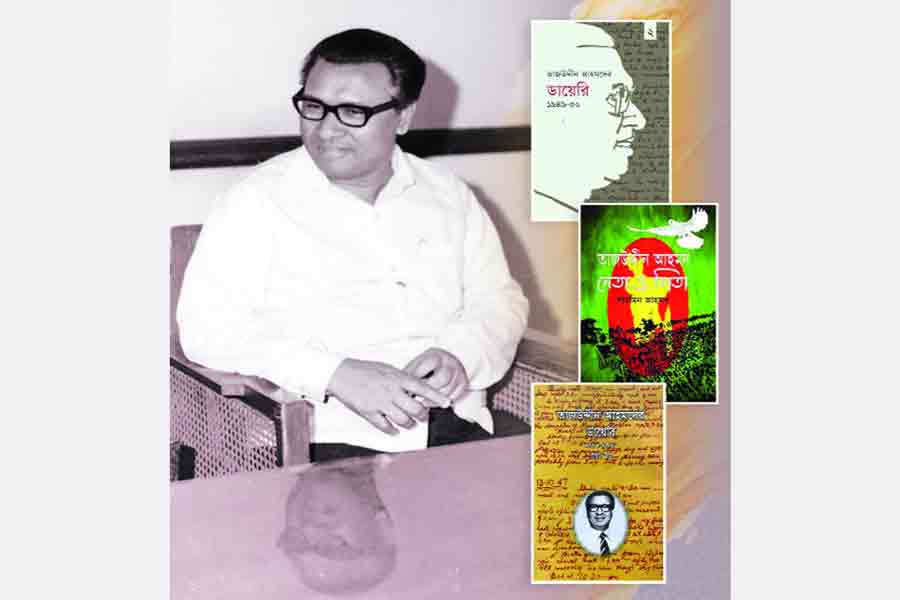

The rest of my account of working with Tajuddin Ahmad during the Liberation War is documented in detail in my book Muldhara '71.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.

MH: At that time, a Punjabi man named Jafar Naqvi lived next to my house. He had served as the Chief Reporter of The Pakistan Times between 1962 and 1964. We became very close friends. Both of us belonged to the same faction of the Communist Party — the one entangled in the Moscow–China ideological conflict. Like me, he was disillusioned with both sides, though he leaned more towards the pro-Moscow position. I was around 35 years old then, while he was over 40. By that time, he had left journalism and was serving as the resident director of Eastern Refinery Ltd in Chittagong. He frequently travelled between Chittagong and Karachi, as his maternal uncle was the head of the organisation.

Every week, he was required to report to Tikka Khan two to three times regarding Petroleum, Oil, and Lubricants — detailing available stock, goods in transit, and quantities being refined.

He would occasionally drop by and share updates. One day, he suddenly asked, "So, you're still around?" I replied, "Yes, everything seems normal now." He responded, "What normal? Another major crisis is imminent. It's going to happen soon."

He warned, "The Indians are training so many people — do you think Pakistan will just sit idle? They will strike. And once the attack happens, the war will begin."

He advised me to leave, saying, "War is about to begin again." When I asked why, he explained that the Pakistani army was delaying because the Chinese hadn't fully given their nod yet. Pakistan, he said, would find it difficult to go to war alone without clear support from China.

Within our group, we quietly gathered information. Shahidullah Kaiser, my mentor in the Communist Party, was a small-built, cheerful man of about 45. We met almost daily in Dhanmondi, where he, Ahmadul Kabir, and Zohur Hossain Chowdhury would often exchange news.

It was Shahidullah Kaiser who first told me that Tajuddin Ahmad was either in Kolkata or Delhi, and that I should go and find him — someone reliable was needed to brief them on the situation in Dhaka. So, in May, I went to Calcutta. I didn't find Tajuddin right away, but I met Amirul Islam and Nurul Quader first.

Tajuddin Ahmad first shared with me his belief that Mrs Gandhi was a sincere leader who would stand by Bangladesh's cause. In response, I raised a concern — though she may have assured full support, there remained a possibility that if China were to intervene or launch an attack, she might frame it as an external conflict and withdraw her support, leaving us to face the situation alone. This concern stemmed from insights I had received earlier from Jafar Naqvi.

Tajuddin acknowledged the risk but noted that such developments were beyond what they could have anticipated at the time.

I then argued that India's security could only be ensured through a firm assurance from the Soviet Union — specifically, that the Soviets would deter any potential Chinese aggression. I reminded him that China still had around one lakh soldiers deployed along the Ussuri River, and there was fighting between these two countries along the border. If China were to intervene and the Soviet Union formed a formal alliance with India, it could dissuade Chinese action. Only under such an arrangement, I asserted, could India feel genuinely secure. At that point, we had no other support on the global stage.

Tajuddin remained silent for a while and then suggested that I go to Delhi to raise these strategic concerns with Indian policymakers. Following his advice, I went to Delhi to engage with Indian policy-level think tanks.

The rest of my account of working with Tajuddin Ahmad during the Liberation War is documented in detail in my book Muldhara '71.

The interview was taken by Priyam Paul.