Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,949

- Likes

- 8,155

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Why Phillips Curve fails in Bangladesh

In simple terms, the Phillips Curve proposes a trade-off: when an economy grows rapidly and jobs become plentiful, prices tend to rise faster; when unemployment is high, inflation tends to slow. In other words, a country may tolerate some inflation to achieve more employment or accept higher unempl

Why Phillips Curve fails in Bangladesh

Abdullah A Dewan

Published :

Jan 28, 2026 23:08

Updated :

Jan 28, 2026 23:08

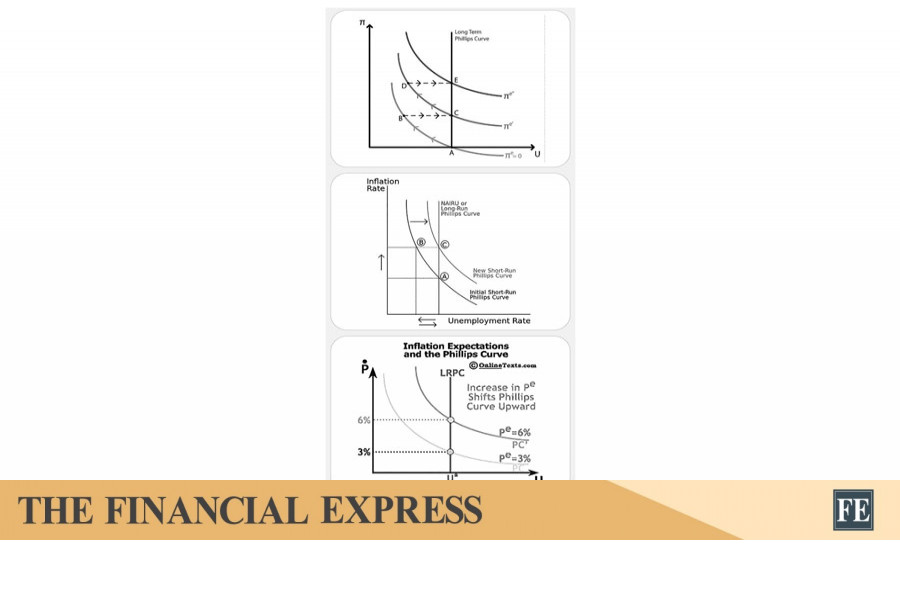

In simple terms, the Phillips Curve proposes a trade-off: when an economy grows rapidly and jobs become plentiful, prices tend to rise faster; when unemployment is high, inflation tends to slow. In other words, a country may tolerate some inflation to achieve more employment or accept higher unemployment to stabilize prices. Developed in the context of relatively well-functioning market economies, this idea once shaped how governments thought about growth, inflation, and stabilization policy.

The Phillips Curve was never conceived as a mathematical law. It began as an empirical observation-a mid-20th-century British pattern linking unemployment to wage growth under specific institutional conditions. Only later was this relationship incorporated into formal macroeconomic models. As an empirical regularity rather than a universal rule, the Phillips relationship is inherently context dependent. Where labour markets are informal, price formation is distorted by non-market forces, and inflation is driven by external shocks or organized rent extraction-as in Bangladesh-the pattern has no reason to appear.

Time and technology have further weakened the relationship. Identified in the late 1950s, the curve emerged in an era of nationally bounded economies, strong trade unions, limited capital mobility, and stable industrial employment. Globalisation, automation, financialisation, and fragmented labour markets have since altered how wages, prices, and employment interact. Even in advanced economies, inflation has become less responsive to labour-market tightness as global supply chains, imported inflation, productivity shocks, and market concentration dilute wage-price transmission. In Bangladesh-marked by informality, external price pass-through, and non-market power-the structural distance from the original Phillips context is even greater.

Crucially, the Phillips Curve applies to economies where market forces dominate wage and price formation and non-market frictions remain limited. It is best treated here as a theoretical benchmark, not an empirical description of Bangladesh's inflation-employment dynamics.

In modern macroeconomics, this benchmark is formalized through the inflation-expectations-augmented Phillips Curve. In this framework, the short-run relationship between inflation and unemployment depends critically on expected inflation. Temporary demand expansion may reduce unemployment only so long as inflation expectations remain unchanged. Once workers and firms revise their expectations upward, inflation rises without delivering lasting employment gains, and unemployment returns to its natural rate. The long-run Phillips Curve is therefore vertical, reflecting the reality that inflation cannot permanently buy jobs. This expectations channel-central to policy credibility in advanced economies-already presumes functioning labour markets, coherent price signals, and institutional trust. Where these conditions fail, the Phillips mechanism does not merely weaken; it loses its operational meaning.

The logic behind the Phillips Curve is straightforward. When jobs are abundant, workers gain bargaining power, wages rise, firms face higher costs, and prices increase. When unemployment is high, wage pressure eases and inflation slows. For this mechanism to function, wages and prices must be set primarily through decentralized market interactions rather than administrative controls, cartel power, political interference, or coercive extraction. Once non-market forces dominate price formation, the inflation-unemployment trade-off collapses.

In Bangladesh, the Phillips Curve has never matured into a durable macroeconomic reality. It has appeared briefly and conditionally. Over the past twelve months, even under an interim government ostensibly freed from partisan compulsions, the curve has remained conspicuously absent. The reasons are not technical; they are structural, political, and institutional.

Bangladesh's macroeconomic history shows that the Phillips mechanism requires conditions the country rarely enjoys simultaneously. Inflation must be predominantly demand-pull rather than imported or supply driven. Labour markets must transmit tightness into wages. Monetary policy must credibly anchor expectations. Historically, none has held consistently. The only episode faintly resembling a Phillips-type relationship occurred in the mid-1990s, when growth accelerated, exchange-rate stability limited imported inflation, and food prices were subdued. Even then, the relationship was fragile. Floods, external shocks, and structural bottlenecks quickly overwhelmed it. Inflation resumed its familiar pattern-driven not by overheating labor markets but by food, fuel, logistics, and currency pressures.

The deeper reason lies in the nature of employment itself. Bangladesh's unemployment rate has always been a statistical mirage. With more than four-fifths of the workforce informal, open unemployment is neither a meaningful measure of slack nor a reliable transmitter of macroeconomic pressure. Underemployment absorbs shocks silently. Workers adjust hours, intensity, and survival strategies rather than bargain for higher wages. The Phillips Curve presumes a wage-price spiral; Bangladesh experiences a price-shock spiral instead.

Against this background, the failure of the interim government over the last year to engineer even a weak Phillips-type outcome should not surprise. Inflation remained elevated while employment conditions failed to improve meaningfully. Crucially, this inflation was not the kind policy stimulus could trade off against unemployment. It was driven by exchange-rate depreciation, global commodity pass-through, energy pricing adjustments, and-most corrosively-domestic market distortions rooted in corruption and extortion.

Here political economy matters more than textbook macroeconomics. Bangladesh's price formation mechanism is not competitive in the classical sense. Key commodity markets-rice, edible oil, onions, construction materials, transport services-are dominated by entrenched syndicates. These syndicates do not merely exploit shortages; they manufacture them. Hoarding, coordinated supply withholding, and price leadership ensure that even when global prices soften or domestic production improves, retail prices remain sticky upward. Inflation is therefore not a signal of excess demand; it is a tax imposed by organised rent-seeking.

The interim government inherited this architecture but lacked the coercive, institutional, and political capital to dismantle it. Administrative orders, moral suasion, and sporadic enforcement cannot break syndicates embedded in party financing, local power structures, and bureaucratic collusion. As long as extortion networks extract rents at wholesale markets, transport nodes, ports, and distribution chains, inflation remains structurally decoupled from employment conditions.

Monetary policy is equally constrained. Tightening credit in such an environment does not primarily suppress excess demand; it raises costs for small firms, traders, and consumers while leaving syndicate pricing power intact. Higher interest rates are passed on to consumers. Employment weakens, inflation persists, and the trade-off collapses. This is not a Phillips Curve failure of calibration; it is a failure of transmission. Fiscal policy offers no better lever. Spending restraint does little to cool food- and fuel-driven inflation, while expansion risks widening deficits without improving employment quality.

Corruption compounds the problem by distorting expectations. In a credible Phillips framework, workers, firms, and policymakers share beliefs about future inflation. In Bangladesh, expectations are unanchored because economic outcomes are routinely overridden by non-economic forces: toll extortion, selective impunity, and political interference. When prices rise, households do not interpret it as overheating; they interpret it as organized extraction. Such expectations harden inflation rather than soften it, rendering demand management ineffective.

What governs Bangladesh's inflation-employment dynamics is not a trade-off but a hierarchy. Prices respond less to labor-market conditions than to control over economic chokepoints-ports, transport corridors, wholesale markets, energy pricing, and regulatory discretion. Inflation rises not when workers gain bargaining power, but when syndicates exercise it. Employment expands not by tightening labour markets, but by dispersing risk across informality. In such a system, inflation is detached from prosperity and employment from productivity.

The past year reinforces a sobering conclusion. Bangladesh does not fail to achieve the Phillips Curve because policymakers misunderstand macroeconomics. It fails because the economy's institutional wiring does not allow the curve to exist. Inflation is not the price of prosperity; it is the symptom of governance failure. The Phillips Curve in Bangladesh is not merely weak; it is structurally displaced. It flickers briefly under benign conditions, then disappears under corruption, informality, and political capture. The interim government did not fail to bend the curve; it confronted an economy where the curve was never designed to function.

Dr. Abdullah A. Dewan, Professor Emeritus of Economics, Eastern Michigan University (USA); former physicist and nuclear engineer, Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission (BAEC).

Abdullah A Dewan

Published :

Jan 28, 2026 23:08

Updated :

Jan 28, 2026 23:08

In simple terms, the Phillips Curve proposes a trade-off: when an economy grows rapidly and jobs become plentiful, prices tend to rise faster; when unemployment is high, inflation tends to slow. In other words, a country may tolerate some inflation to achieve more employment or accept higher unemployment to stabilize prices. Developed in the context of relatively well-functioning market economies, this idea once shaped how governments thought about growth, inflation, and stabilization policy.

The Phillips Curve was never conceived as a mathematical law. It began as an empirical observation-a mid-20th-century British pattern linking unemployment to wage growth under specific institutional conditions. Only later was this relationship incorporated into formal macroeconomic models. As an empirical regularity rather than a universal rule, the Phillips relationship is inherently context dependent. Where labour markets are informal, price formation is distorted by non-market forces, and inflation is driven by external shocks or organized rent extraction-as in Bangladesh-the pattern has no reason to appear.

Time and technology have further weakened the relationship. Identified in the late 1950s, the curve emerged in an era of nationally bounded economies, strong trade unions, limited capital mobility, and stable industrial employment. Globalisation, automation, financialisation, and fragmented labour markets have since altered how wages, prices, and employment interact. Even in advanced economies, inflation has become less responsive to labour-market tightness as global supply chains, imported inflation, productivity shocks, and market concentration dilute wage-price transmission. In Bangladesh-marked by informality, external price pass-through, and non-market power-the structural distance from the original Phillips context is even greater.

Crucially, the Phillips Curve applies to economies where market forces dominate wage and price formation and non-market frictions remain limited. It is best treated here as a theoretical benchmark, not an empirical description of Bangladesh's inflation-employment dynamics.

In modern macroeconomics, this benchmark is formalized through the inflation-expectations-augmented Phillips Curve. In this framework, the short-run relationship between inflation and unemployment depends critically on expected inflation. Temporary demand expansion may reduce unemployment only so long as inflation expectations remain unchanged. Once workers and firms revise their expectations upward, inflation rises without delivering lasting employment gains, and unemployment returns to its natural rate. The long-run Phillips Curve is therefore vertical, reflecting the reality that inflation cannot permanently buy jobs. This expectations channel-central to policy credibility in advanced economies-already presumes functioning labour markets, coherent price signals, and institutional trust. Where these conditions fail, the Phillips mechanism does not merely weaken; it loses its operational meaning.

The logic behind the Phillips Curve is straightforward. When jobs are abundant, workers gain bargaining power, wages rise, firms face higher costs, and prices increase. When unemployment is high, wage pressure eases and inflation slows. For this mechanism to function, wages and prices must be set primarily through decentralized market interactions rather than administrative controls, cartel power, political interference, or coercive extraction. Once non-market forces dominate price formation, the inflation-unemployment trade-off collapses.

In Bangladesh, the Phillips Curve has never matured into a durable macroeconomic reality. It has appeared briefly and conditionally. Over the past twelve months, even under an interim government ostensibly freed from partisan compulsions, the curve has remained conspicuously absent. The reasons are not technical; they are structural, political, and institutional.

Bangladesh's macroeconomic history shows that the Phillips mechanism requires conditions the country rarely enjoys simultaneously. Inflation must be predominantly demand-pull rather than imported or supply driven. Labour markets must transmit tightness into wages. Monetary policy must credibly anchor expectations. Historically, none has held consistently. The only episode faintly resembling a Phillips-type relationship occurred in the mid-1990s, when growth accelerated, exchange-rate stability limited imported inflation, and food prices were subdued. Even then, the relationship was fragile. Floods, external shocks, and structural bottlenecks quickly overwhelmed it. Inflation resumed its familiar pattern-driven not by overheating labor markets but by food, fuel, logistics, and currency pressures.

The deeper reason lies in the nature of employment itself. Bangladesh's unemployment rate has always been a statistical mirage. With more than four-fifths of the workforce informal, open unemployment is neither a meaningful measure of slack nor a reliable transmitter of macroeconomic pressure. Underemployment absorbs shocks silently. Workers adjust hours, intensity, and survival strategies rather than bargain for higher wages. The Phillips Curve presumes a wage-price spiral; Bangladesh experiences a price-shock spiral instead.

Against this background, the failure of the interim government over the last year to engineer even a weak Phillips-type outcome should not surprise. Inflation remained elevated while employment conditions failed to improve meaningfully. Crucially, this inflation was not the kind policy stimulus could trade off against unemployment. It was driven by exchange-rate depreciation, global commodity pass-through, energy pricing adjustments, and-most corrosively-domestic market distortions rooted in corruption and extortion.

Here political economy matters more than textbook macroeconomics. Bangladesh's price formation mechanism is not competitive in the classical sense. Key commodity markets-rice, edible oil, onions, construction materials, transport services-are dominated by entrenched syndicates. These syndicates do not merely exploit shortages; they manufacture them. Hoarding, coordinated supply withholding, and price leadership ensure that even when global prices soften or domestic production improves, retail prices remain sticky upward. Inflation is therefore not a signal of excess demand; it is a tax imposed by organised rent-seeking.

The interim government inherited this architecture but lacked the coercive, institutional, and political capital to dismantle it. Administrative orders, moral suasion, and sporadic enforcement cannot break syndicates embedded in party financing, local power structures, and bureaucratic collusion. As long as extortion networks extract rents at wholesale markets, transport nodes, ports, and distribution chains, inflation remains structurally decoupled from employment conditions.

Monetary policy is equally constrained. Tightening credit in such an environment does not primarily suppress excess demand; it raises costs for small firms, traders, and consumers while leaving syndicate pricing power intact. Higher interest rates are passed on to consumers. Employment weakens, inflation persists, and the trade-off collapses. This is not a Phillips Curve failure of calibration; it is a failure of transmission. Fiscal policy offers no better lever. Spending restraint does little to cool food- and fuel-driven inflation, while expansion risks widening deficits without improving employment quality.

Corruption compounds the problem by distorting expectations. In a credible Phillips framework, workers, firms, and policymakers share beliefs about future inflation. In Bangladesh, expectations are unanchored because economic outcomes are routinely overridden by non-economic forces: toll extortion, selective impunity, and political interference. When prices rise, households do not interpret it as overheating; they interpret it as organized extraction. Such expectations harden inflation rather than soften it, rendering demand management ineffective.

What governs Bangladesh's inflation-employment dynamics is not a trade-off but a hierarchy. Prices respond less to labor-market conditions than to control over economic chokepoints-ports, transport corridors, wholesale markets, energy pricing, and regulatory discretion. Inflation rises not when workers gain bargaining power, but when syndicates exercise it. Employment expands not by tightening labour markets, but by dispersing risk across informality. In such a system, inflation is detached from prosperity and employment from productivity.

The past year reinforces a sobering conclusion. Bangladesh does not fail to achieve the Phillips Curve because policymakers misunderstand macroeconomics. It fails because the economy's institutional wiring does not allow the curve to exist. Inflation is not the price of prosperity; it is the symptom of governance failure. The Phillips Curve in Bangladesh is not merely weak; it is structurally displaced. It flickers briefly under benign conditions, then disappears under corruption, informality, and political capture. The interim government did not fail to bend the curve; it confronted an economy where the curve was never designed to function.

Dr. Abdullah A. Dewan, Professor Emeritus of Economics, Eastern Michigan University (USA); former physicist and nuclear engineer, Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission (BAEC).