Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,835

- Likes

- 8,152

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Economic reading of BD's 2025 ordinances

In 2025, Bangladesh's interim government issued 78 ordinances covering labour rights, judicial procedures, digital security, and constitutional governance. These ordinances carry economic consequences. As economic activity is ultimately governed by law, changes in rules and institutions directly af

Economic reading of BD's 2025 ordinances

Syed Abul Basher

Published :

Jan 27, 2026 22:58

Updated :

Jan 27, 2026 22:58

In 2025, Bangladesh's interim government issued 78 ordinances covering labour rights, judicial procedures, digital security, and constitutional governance. These ordinances carry economic consequences. As economic activity is ultimately governed by law, changes in rules and institutions directly affect transaction costs, property rights, and investment incentives. In turn, these legal changes alter expected returns, risks, and bargaining positions.

Previously, to form a union, workers needed to meet a 20 per cent membership threshold. This meant that a factory with 100 workers required mobilising 20 workers, whereas a factory with 500 workers needed 100 workers to form a union. For medium to large factories, meeting this threshold was difficult, since employers could easily intimidate key organisers to prevent unionisation. The 2025 Labour (Amendment) Ordinance addressed this barrier by moving from a percentage-based rule to a fixed-number approach. Factories with 20-300 employees can now form a union with just 20 workers. This change came partly in response to criticism from the European Union (EU) and International Labor Organization (ILO), which argued that the percentage rule blocked workers from exercising freedom of association.

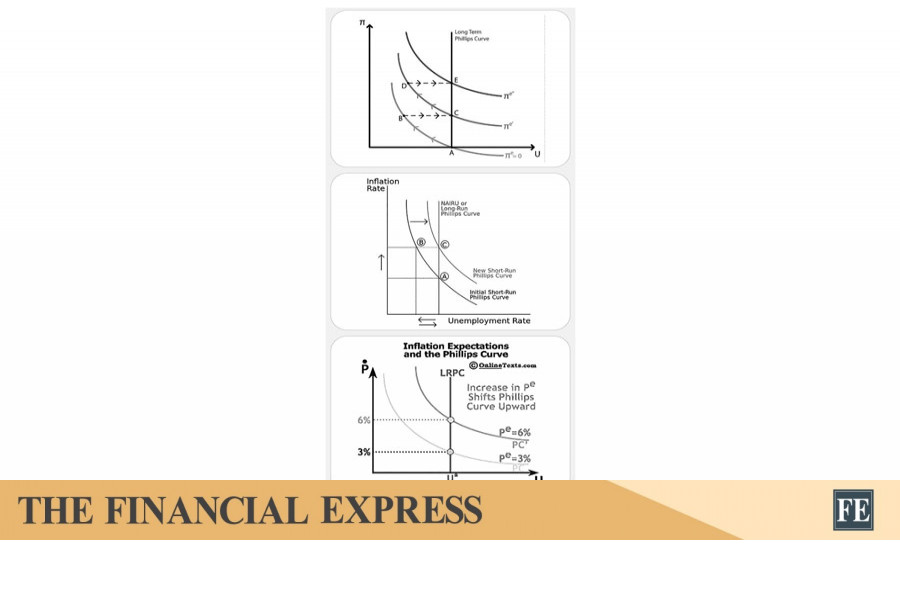

From an economic standpoint, this reduces the fixed cost of collective action. It shifts the Nash bargaining position of workers upward, allowing them to capture a larger share of firm surplus. The reform also raises penalties for unfair labour practices under Sections 294-295, increasing the expected cost of anti-union behaviour. The combined effect is to raise expected wages and job security, but also to increase unit labour costs faced by firms. Whether this improves stability or raises conflict is an empirical question, but incentives have clearly shifted.

Currently, Bangladesh's garment exports to the EU enjoy duty-free access under the Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme. After 2029, to continue enjoying preferential access, Bangladesh will need to qualify for GSP-plus, which requires compliance with labour rights conventions. Losing this status would impose tariffs of roughly 9-12 per cent on garments. This amounts to a negative price shock to Bangladeshi exports. Unless firms can pass costs to buyers, a 10 per cent tariff reduces exporter revenue and profitability by roughly the same margin. Since Bangladesh operates in a highly competitive global garment market, most of the burden would fall on domestic producers and workers.

The labour reforms should therefore be understood as an investment in market access. By raising compliance today, Bangladesh lowers the probability of a catastrophic trade shock tomorrow. In expected-value terms, modest increases in labour costs now can be justified if they reduce the risk of losing billions of dollars in export earnings later.

Belatedly, the Women and Children Repression Prevention Ordinance expanded the legal definition of sexual violence and strengthened penalties, while the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) amendments made it possible to prosecute organisations, not just individuals, for political violence. These changes increase the expected cost of committing or tolerating violence. When legal protection is weak, violence and fear discourage women from travelling, working, or staying in school-reducing labour force participation and human-capital investment. Stronger enforcement can raise the return to education and formal work, particularly for girls. The same logic applies to investors. When organised political violence carries a higher legal risk, long-term investment becomes safer, lowering the political-risk premium built into interest rates and foreign investment decisions.

For too long, Bangladesh's judicial system has imposed high transaction costs on economic activity. It often took many years to settle commercial disputes, or sometimes they remained unresolved. As a result, capital was tied up, raising the effective cost of doing business. Meanwhile, arbitrary enforcement created legal uncertainty that discouraged formal contracting and long-term investment. The 2025 legislative reforms attempt to address these frictions by reducing delays and discretion.

Under the amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), police are now required to identify themselves during arrests, prepare written arrest memoranda, and maintain digital records. The expansion of magistrates' fine-imposing powers will likely speed case resolution by allowing minor cases to be resolved without full trials. These changes not only reduce arbitrary enforcement risk but also increase the predictability of legal outcomes. Together, these reforms will likely lower state opportunism and the regulatory burden on firms and households.

Similarly, under the new Civil Procedure Code (CPC), courts now accept electronic service of summons through SMS, voice calls, and messaging apps, allowing judges to hear more cases per day. Moreover, to discourage frivolous litigation, compensation for false claims has increased to Tk 50,000. Importantly, the separation of civil and criminal courts at the district level allows judges to specialise rather than handling both types of cases. Together, these amendments make contract enforcement faster and more reliable, freeing up capital and improving its allocation across the economy.

The economic payoff from these judicial reforms, however, depends on enforcement capacity. As of December 2024, Bangladesh faced a backlog of over 45 lakh cases. Unless the government recruits more judges, builds more courtrooms, and implements functioning digital systems, procedural reforms alone will not be enough. In economic terms, unless these rules are credibly enforced, the underlying transaction costs of doing business will remain high, and private investment and productivity will not respond.

A longstanding problem in Bangladesh is weak credible commitment. Independent institutions such as the judiciary, election bodies, and anti-corruption agencies have long been seen as politically captured, raising doubts about property rights and policy stability. The proposed constitutional reforms aim to disperse power more widely. A bicameral legislature with a proportional upper house would ensure continued opposition influence. Key oversight committees would be assigned to opposition members. A ten-year limit on the prime minister would reduce power concentration. Making the Anti-Corruption Commission a constitutional body would increase its independence.

Economically, these reforms function as commitment devices. Bangladesh's sovereign bonds have historically traded at spreads of 200-400 basis points above comparable economies, reflecting political risk. More credible institutions can reduce these spreads and borrowing costs.

Finally, the previous Digital Security Act (DSA) had created a climate of legal unpredictability. The new ordinance makes most offenses bailable while retaining protections against cybercrime. This is welcome for digital entrepreneurs as it lowers the downside risk. With reduced legal risk, the expected return to innovation rises. As software and IT exports depend more on human capital than physical infrastructure, legal predictability is a binding input into sectoral growth.

Bangladesh already has many good laws. But enforcement is the binding constraint. In economic terms, laws without enforcement are meaningless contracts. Unless labour inspectors, courts, regulators, and the ACC are adequately staffed and insulated from political pressure, the ordinances will not change incentives. Trade partners and financial markets respond to outcomes, not statutes.

The 2025 ordinances are economically coherent responses to Bangladesh's vulnerabilities as a trade-dependent, investment-constrained economy-attempting to improve labour credibility, reduce transaction costs, lower political risk, and stimulate innovation. If implemented credibly, these reforms can raise the expected return to investment and human capital, moving Bangladesh onto a higher growth path. If not, they will remain symbolic, and the economic risks facing the country will persist.

Syed Abul Basher

Published :

Jan 27, 2026 22:58

Updated :

Jan 27, 2026 22:58

In 2025, Bangladesh's interim government issued 78 ordinances covering labour rights, judicial procedures, digital security, and constitutional governance. These ordinances carry economic consequences. As economic activity is ultimately governed by law, changes in rules and institutions directly affect transaction costs, property rights, and investment incentives. In turn, these legal changes alter expected returns, risks, and bargaining positions.

Previously, to form a union, workers needed to meet a 20 per cent membership threshold. This meant that a factory with 100 workers required mobilising 20 workers, whereas a factory with 500 workers needed 100 workers to form a union. For medium to large factories, meeting this threshold was difficult, since employers could easily intimidate key organisers to prevent unionisation. The 2025 Labour (Amendment) Ordinance addressed this barrier by moving from a percentage-based rule to a fixed-number approach. Factories with 20-300 employees can now form a union with just 20 workers. This change came partly in response to criticism from the European Union (EU) and International Labor Organization (ILO), which argued that the percentage rule blocked workers from exercising freedom of association.

From an economic standpoint, this reduces the fixed cost of collective action. It shifts the Nash bargaining position of workers upward, allowing them to capture a larger share of firm surplus. The reform also raises penalties for unfair labour practices under Sections 294-295, increasing the expected cost of anti-union behaviour. The combined effect is to raise expected wages and job security, but also to increase unit labour costs faced by firms. Whether this improves stability or raises conflict is an empirical question, but incentives have clearly shifted.

Currently, Bangladesh's garment exports to the EU enjoy duty-free access under the Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme. After 2029, to continue enjoying preferential access, Bangladesh will need to qualify for GSP-plus, which requires compliance with labour rights conventions. Losing this status would impose tariffs of roughly 9-12 per cent on garments. This amounts to a negative price shock to Bangladeshi exports. Unless firms can pass costs to buyers, a 10 per cent tariff reduces exporter revenue and profitability by roughly the same margin. Since Bangladesh operates in a highly competitive global garment market, most of the burden would fall on domestic producers and workers.

The labour reforms should therefore be understood as an investment in market access. By raising compliance today, Bangladesh lowers the probability of a catastrophic trade shock tomorrow. In expected-value terms, modest increases in labour costs now can be justified if they reduce the risk of losing billions of dollars in export earnings later.

Belatedly, the Women and Children Repression Prevention Ordinance expanded the legal definition of sexual violence and strengthened penalties, while the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) amendments made it possible to prosecute organisations, not just individuals, for political violence. These changes increase the expected cost of committing or tolerating violence. When legal protection is weak, violence and fear discourage women from travelling, working, or staying in school-reducing labour force participation and human-capital investment. Stronger enforcement can raise the return to education and formal work, particularly for girls. The same logic applies to investors. When organised political violence carries a higher legal risk, long-term investment becomes safer, lowering the political-risk premium built into interest rates and foreign investment decisions.

For too long, Bangladesh's judicial system has imposed high transaction costs on economic activity. It often took many years to settle commercial disputes, or sometimes they remained unresolved. As a result, capital was tied up, raising the effective cost of doing business. Meanwhile, arbitrary enforcement created legal uncertainty that discouraged formal contracting and long-term investment. The 2025 legislative reforms attempt to address these frictions by reducing delays and discretion.

Under the amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), police are now required to identify themselves during arrests, prepare written arrest memoranda, and maintain digital records. The expansion of magistrates' fine-imposing powers will likely speed case resolution by allowing minor cases to be resolved without full trials. These changes not only reduce arbitrary enforcement risk but also increase the predictability of legal outcomes. Together, these reforms will likely lower state opportunism and the regulatory burden on firms and households.

Similarly, under the new Civil Procedure Code (CPC), courts now accept electronic service of summons through SMS, voice calls, and messaging apps, allowing judges to hear more cases per day. Moreover, to discourage frivolous litigation, compensation for false claims has increased to Tk 50,000. Importantly, the separation of civil and criminal courts at the district level allows judges to specialise rather than handling both types of cases. Together, these amendments make contract enforcement faster and more reliable, freeing up capital and improving its allocation across the economy.

The economic payoff from these judicial reforms, however, depends on enforcement capacity. As of December 2024, Bangladesh faced a backlog of over 45 lakh cases. Unless the government recruits more judges, builds more courtrooms, and implements functioning digital systems, procedural reforms alone will not be enough. In economic terms, unless these rules are credibly enforced, the underlying transaction costs of doing business will remain high, and private investment and productivity will not respond.

A longstanding problem in Bangladesh is weak credible commitment. Independent institutions such as the judiciary, election bodies, and anti-corruption agencies have long been seen as politically captured, raising doubts about property rights and policy stability. The proposed constitutional reforms aim to disperse power more widely. A bicameral legislature with a proportional upper house would ensure continued opposition influence. Key oversight committees would be assigned to opposition members. A ten-year limit on the prime minister would reduce power concentration. Making the Anti-Corruption Commission a constitutional body would increase its independence.

Economically, these reforms function as commitment devices. Bangladesh's sovereign bonds have historically traded at spreads of 200-400 basis points above comparable economies, reflecting political risk. More credible institutions can reduce these spreads and borrowing costs.

Finally, the previous Digital Security Act (DSA) had created a climate of legal unpredictability. The new ordinance makes most offenses bailable while retaining protections against cybercrime. This is welcome for digital entrepreneurs as it lowers the downside risk. With reduced legal risk, the expected return to innovation rises. As software and IT exports depend more on human capital than physical infrastructure, legal predictability is a binding input into sectoral growth.

Bangladesh already has many good laws. But enforcement is the binding constraint. In economic terms, laws without enforcement are meaningless contracts. Unless labour inspectors, courts, regulators, and the ACC are adequately staffed and insulated from political pressure, the ordinances will not change incentives. Trade partners and financial markets respond to outcomes, not statutes.

The 2025 ordinances are economically coherent responses to Bangladesh's vulnerabilities as a trade-dependent, investment-constrained economy-attempting to improve labour credibility, reduce transaction costs, lower political risk, and stimulate innovation. If implemented credibly, these reforms can raise the expected return to investment and human capital, moving Bangladesh onto a higher growth path. If not, they will remain symbolic, and the economic risks facing the country will persist.