- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #201

Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 15,344

- Reaction score

- 7,857

- Points

- 209

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

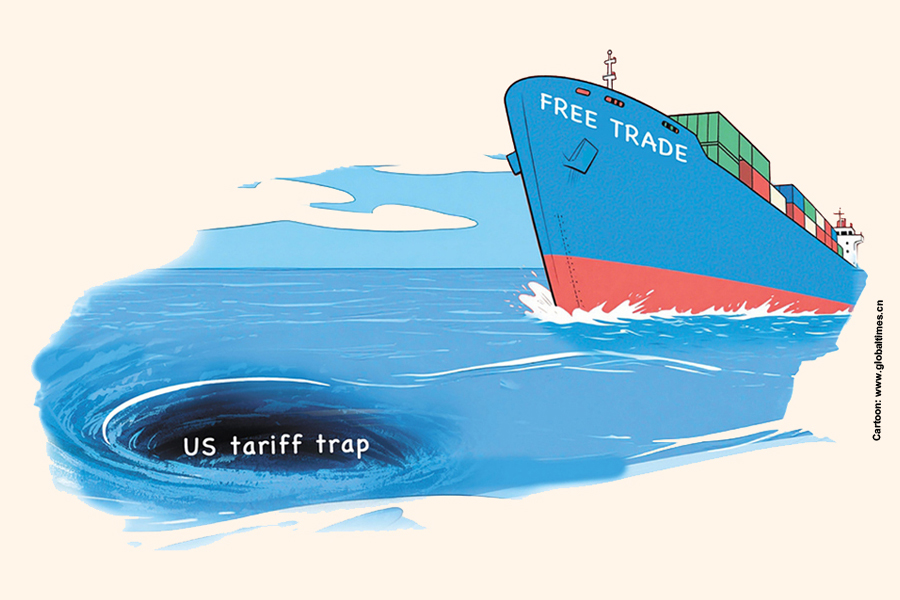

Donald Trump is using tariff as a weapon of choice

Upending text book theories on tariff, President Donald Trump is using tariff as a weapon of choice for multiple objectives. This has made the existing rule-based global trading system go haywire, making the predictable and transparent multilateral trading system put in place by Uruguay Round of tr

Donald Trump is using tariff as a weapon of choice

Hasnat Abdul Hye

Published :

Aug 10, 2025 22:38

Updated :

Aug 10, 2025 22:41

Upending text book theories on tariff, President Donald Trump is using tariff as a weapon of choice for multiple objectives. This has made the existing rule-based global trading system go haywire, making the predictable and transparent multilateral trading system put in place by Uruguay Round of trade negotiations and since 1995 by the World Trading Organization (WTO), irrelevant.

Traditionally, tariffs have been slapped by countries to shield domestic industries and to raise revenue. An extension of the former has been the 'infant industry' argument given by newly industrialising countries. Tariffs have been imposed by countries in retaliation of higher rates of tariff by other countries enjoying lower rates from it. President Trump has unleashed a tariff war during his second term with political objectives in addition to the traditional objectives which makes tariff a weapon of choice on multiple fronts. This makes tariff no less lethal than other weapons of mass destruction. The fact that president Trump is using it against all countries, friend or foe, makes this disastrous for the global trading system and the global economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already forecast a slower growth rate for world economy in the coming years because of uncertainty about the global trade volume resulting from unpredictable tariff regime of America, the largest economy in the world. In April this year, IMF in its Update on Global Economy reduced the rate of growth by as high as 0.5 per cent and forecast the growth for 2025 at 2.8 per cent. The percentage for 2026 has been placed at 3 per cent after reducing 0.3 per cent. The IMF squarely held the turmoil in global trade resulting from tit-for-tat tariff imposition responsible for this anaemic growth of the world economy.

It is understandable that facing a trade deficit of $1.3 trillion America under president Trump would like to reduce the deficit. In achieving this the Trump administration had theoretically two options: (a) to ask its trading partners to buy more from it; (b) to reduce imports from other countries through quantitative restrictions or slapping high tariff rates that would result in reduced imports. Given the higher prices of American goods the first option was a non-starter through the market mechanism. Faced with this reality, the Trump Administration settled for the second option. But instead of gradual increase in existing tariff, very high rates were announced that shocked the trading partners. Effective on April 1, 2025, the so called 'liberation day' of America, all countries faced a base tariff rate of 10 per cent, on top of which was imposed what was called 'reciprocal' tariff rates that varied among countries depending on their tariff rates for American goods. Then a period of three months, ending on July 31, was announced as 'pause' for bilateral negotiations to reach trade deals. Some countries like Japan 'successfully' completed bi-lateral negotiation and America agreed to a reciprocal tariff rate of 15 per cent on automobiles and parts, down from 25 per cent imposed earlier. But steel and aluminium are excluded from this and still face 50 per cent tariff. In addition, Japan has to make investments in selected sectors, amounting to $550 billion in America over the near future. Furthermore, Japan has to buy American agricultural and defence items in greater volume than now. Under the negotiated deal, Japan has to buy 100 Boeing aircrafts and jointly invest in Alaska LNG development.

The concessions extracted from Japan in lieu of reducing the earlier tariff rate of 25 per cent to 15 per cent reveal the broad objectives of the strategy in trade negotiations that have been conducted by Trump Administration. It is not simply arm twisting, but downright economic blackmailing. It may be asked why countries like Japan could not refuse to agree to such coercive methods and harsh terms? The answer is, having become dependent on the big American market for vital exports like automobiles and auto parts it is difficult for the country to wean itself away from that market all on a sudden. Even with time, it may be impossible to replace American market for certain export items by another market because of its size. Japan is not an exception. Many other countries suffer from this problem of integration to American market and Trump Administration is taking full advantage of this to extract maximum concessions from its trading partners. This explains why Bangladesh had to agree to purchase 35 Boeing aircraft and buy other items even if at higher prices than in the international market. Without the big American market, Bangladesh's garment industry will suffer such a setback that will be impossible to recover from. All countries trading with America have this disadvantage and America is exploiting this to the hilt.

The rest of the world is going to reward America with higher imports and for some countries, higher off-shore investment, under duress lest its big market is lost. In the process the trading partners will be importing inflation from America through payment of higher prices for American goods and services. American manufactures lost the world market for many goods because of higher cost of production, resulting from higher wages and salaries. Now America has found a way out to overcome that disadvantage by weaponising tariff. After the disastrous use of tariff in the Great Depression years of the '30s many thought that tariff had lost its cachet as an instrument of macroeconomic policy. It required a bully like Donald Trump to prove them wrong. The problem is, this tariff regime, with attached coercive measures, may outlive Donald Trump as his successors will be loath to part with a dispensation that makes their life easier and that of their compatriots comfortable.

President Trump must be given the credit for using tariff for reasons other than economic, making it a weapon of multiple uses. His tariff policy has targeted Brazil for 50 per cent tariff for putting his friend, the former Brazilian president Bolsenero, in trial. Likewise, he has threatened higher tariff on Canada for its intention to recognise the state of Palestine. Trump's former buddy Narendra Modi has not fared better for buying oil and gas from Russia. India has been slapped with a steep tariff at 50 per cent. In the midst of great uncertainty, one thing is certain: in Economics 101, tariff and trade will not be taught in the good old way. The makeover given to the concept by the current president of America will defy the conventional wisdom in academia.

Hasnat Abdul Hye

Published :

Aug 10, 2025 22:38

Updated :

Aug 10, 2025 22:41

Upending text book theories on tariff, President Donald Trump is using tariff as a weapon of choice for multiple objectives. This has made the existing rule-based global trading system go haywire, making the predictable and transparent multilateral trading system put in place by Uruguay Round of trade negotiations and since 1995 by the World Trading Organization (WTO), irrelevant.

Traditionally, tariffs have been slapped by countries to shield domestic industries and to raise revenue. An extension of the former has been the 'infant industry' argument given by newly industrialising countries. Tariffs have been imposed by countries in retaliation of higher rates of tariff by other countries enjoying lower rates from it. President Trump has unleashed a tariff war during his second term with political objectives in addition to the traditional objectives which makes tariff a weapon of choice on multiple fronts. This makes tariff no less lethal than other weapons of mass destruction. The fact that president Trump is using it against all countries, friend or foe, makes this disastrous for the global trading system and the global economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already forecast a slower growth rate for world economy in the coming years because of uncertainty about the global trade volume resulting from unpredictable tariff regime of America, the largest economy in the world. In April this year, IMF in its Update on Global Economy reduced the rate of growth by as high as 0.5 per cent and forecast the growth for 2025 at 2.8 per cent. The percentage for 2026 has been placed at 3 per cent after reducing 0.3 per cent. The IMF squarely held the turmoil in global trade resulting from tit-for-tat tariff imposition responsible for this anaemic growth of the world economy.

It is understandable that facing a trade deficit of $1.3 trillion America under president Trump would like to reduce the deficit. In achieving this the Trump administration had theoretically two options: (a) to ask its trading partners to buy more from it; (b) to reduce imports from other countries through quantitative restrictions or slapping high tariff rates that would result in reduced imports. Given the higher prices of American goods the first option was a non-starter through the market mechanism. Faced with this reality, the Trump Administration settled for the second option. But instead of gradual increase in existing tariff, very high rates were announced that shocked the trading partners. Effective on April 1, 2025, the so called 'liberation day' of America, all countries faced a base tariff rate of 10 per cent, on top of which was imposed what was called 'reciprocal' tariff rates that varied among countries depending on their tariff rates for American goods. Then a period of three months, ending on July 31, was announced as 'pause' for bilateral negotiations to reach trade deals. Some countries like Japan 'successfully' completed bi-lateral negotiation and America agreed to a reciprocal tariff rate of 15 per cent on automobiles and parts, down from 25 per cent imposed earlier. But steel and aluminium are excluded from this and still face 50 per cent tariff. In addition, Japan has to make investments in selected sectors, amounting to $550 billion in America over the near future. Furthermore, Japan has to buy American agricultural and defence items in greater volume than now. Under the negotiated deal, Japan has to buy 100 Boeing aircrafts and jointly invest in Alaska LNG development.

The concessions extracted from Japan in lieu of reducing the earlier tariff rate of 25 per cent to 15 per cent reveal the broad objectives of the strategy in trade negotiations that have been conducted by Trump Administration. It is not simply arm twisting, but downright economic blackmailing. It may be asked why countries like Japan could not refuse to agree to such coercive methods and harsh terms? The answer is, having become dependent on the big American market for vital exports like automobiles and auto parts it is difficult for the country to wean itself away from that market all on a sudden. Even with time, it may be impossible to replace American market for certain export items by another market because of its size. Japan is not an exception. Many other countries suffer from this problem of integration to American market and Trump Administration is taking full advantage of this to extract maximum concessions from its trading partners. This explains why Bangladesh had to agree to purchase 35 Boeing aircraft and buy other items even if at higher prices than in the international market. Without the big American market, Bangladesh's garment industry will suffer such a setback that will be impossible to recover from. All countries trading with America have this disadvantage and America is exploiting this to the hilt.

The rest of the world is going to reward America with higher imports and for some countries, higher off-shore investment, under duress lest its big market is lost. In the process the trading partners will be importing inflation from America through payment of higher prices for American goods and services. American manufactures lost the world market for many goods because of higher cost of production, resulting from higher wages and salaries. Now America has found a way out to overcome that disadvantage by weaponising tariff. After the disastrous use of tariff in the Great Depression years of the '30s many thought that tariff had lost its cachet as an instrument of macroeconomic policy. It required a bully like Donald Trump to prove them wrong. The problem is, this tariff regime, with attached coercive measures, may outlive Donald Trump as his successors will be loath to part with a dispensation that makes their life easier and that of their compatriots comfortable.

President Trump must be given the credit for using tariff for reasons other than economic, making it a weapon of multiple uses. His tariff policy has targeted Brazil for 50 per cent tariff for putting his friend, the former Brazilian president Bolsenero, in trial. Likewise, he has threatened higher tariff on Canada for its intention to recognise the state of Palestine. Trump's former buddy Narendra Modi has not fared better for buying oil and gas from Russia. India has been slapped with a steep tariff at 50 per cent. In the midst of great uncertainty, one thing is certain: in Economics 101, tariff and trade will not be taught in the good old way. The makeover given to the concept by the current president of America will defy the conventional wisdom in academia.