Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,262

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

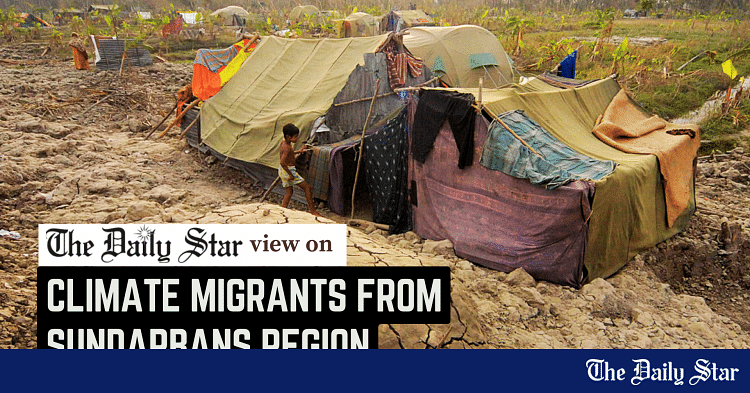

Sundarbans’ climate migrants need help

They must not be left to suffer at home or abroad

Sundarbans’ climate migrants need help

They must not be left to suffer at home or abroad

VISUAL: STAR

We are concerned about the plight of climate migrants who are often forced to seek livelihoods abroad, particularly in the Gulf countries, owing to poverty, debt, and persistent threats of climate-induced disasters in Bangladesh. Far from delivering desired relief, their desperate attempts often turn into another harsh ordeal, as many are forced to return after enduring wage theft, exploitative working conditions, and even deprivation of basic necessities like food in host countries. A significant number of such migrants are from climate-vulnerable regions surrounding the Sundarbans, Satkhira, and Khulna.

Reportedly, climate-related disasters in Bangladesh have nearly doubled over the past six decades, increasing from four per year before 1990 to seven per year after. The frequency and severity of such calamities have further increased after cyclones Sidr in 2007 and Aila in 2009, intensifying migration both within the country and beyond. According to BMET data, international migration from the Sundarbans region increased by 65 percent in a single year, with 786 people moving abroad for work between October 2022 and September 2023, compared to 477 the previous year. Despite that, their financial conditions have remained unchanged.

The picture that emerges from a study by the Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP)—highlighting the experience of returnee migrants belonging to the Sundarbans region—is quite depressing even if familiar. Many have reported suffering withheld salaries, excessive work hours, restricted movement due to confiscation of passports or lack of work permits, and exorbitant recruitment fees. Many were detained by police and deported directly from jail. Their unexpected return without adequate earnings has only deepened their debt burdens instead of easing them.

The picture that emerges from a study by the Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP)—highlighting the experience of returnee migrants belonging to the Sundarbans region—is quite depressing even if familiar. Many have reported suffering withheld salaries, excessive work hours, restricted movement due to confiscation of passports or lack of work permits, and exorbitant recruitment fees. Many were detained by police and deported directly from jail. Their unexpected return without adequate earnings has only deepened their debt burdens instead of easing them. Another recent survey found that nearly every migrant from Bangladesh's climate-affected regions has experienced some form of modern slavery while abroad. This alarming situation demands immediate government interventions, including the creation of adequate local jobs and other income-generating opportunities for climate-vulnerable communities.

The rights and well-being of these inherently vulnerable individuals deserve priority from the authorities. They must actively engage with foreign embassies to safeguard our migrant workers and ensure they are not subjected to exploitation. Also, the authorities must better regulate migration costs and crack down on unscrupulous recruitment agencies preying on desperate job seekers. Over the years, countless workers have faced abuse while abroad, many even losing their lives. This, too, needs to change. The government must take decisive action to address these interlinked issues and uphold the rights of our migrant workers.

They must not be left to suffer at home or abroad

VISUAL: STAR

We are concerned about the plight of climate migrants who are often forced to seek livelihoods abroad, particularly in the Gulf countries, owing to poverty, debt, and persistent threats of climate-induced disasters in Bangladesh. Far from delivering desired relief, their desperate attempts often turn into another harsh ordeal, as many are forced to return after enduring wage theft, exploitative working conditions, and even deprivation of basic necessities like food in host countries. A significant number of such migrants are from climate-vulnerable regions surrounding the Sundarbans, Satkhira, and Khulna.

Reportedly, climate-related disasters in Bangladesh have nearly doubled over the past six decades, increasing from four per year before 1990 to seven per year after. The frequency and severity of such calamities have further increased after cyclones Sidr in 2007 and Aila in 2009, intensifying migration both within the country and beyond. According to BMET data, international migration from the Sundarbans region increased by 65 percent in a single year, with 786 people moving abroad for work between October 2022 and September 2023, compared to 477 the previous year. Despite that, their financial conditions have remained unchanged.

The picture that emerges from a study by the Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP)—highlighting the experience of returnee migrants belonging to the Sundarbans region—is quite depressing even if familiar. Many have reported suffering withheld salaries, excessive work hours, restricted movement due to confiscation of passports or lack of work permits, and exorbitant recruitment fees. Many were detained by police and deported directly from jail. Their unexpected return without adequate earnings has only deepened their debt burdens instead of easing them.

The picture that emerges from a study by the Ovibashi Karmi Unnayan Program (OKUP)—highlighting the experience of returnee migrants belonging to the Sundarbans region—is quite depressing even if familiar. Many have reported suffering withheld salaries, excessive work hours, restricted movement due to confiscation of passports or lack of work permits, and exorbitant recruitment fees. Many were detained by police and deported directly from jail. Their unexpected return without adequate earnings has only deepened their debt burdens instead of easing them. Another recent survey found that nearly every migrant from Bangladesh's climate-affected regions has experienced some form of modern slavery while abroad. This alarming situation demands immediate government interventions, including the creation of adequate local jobs and other income-generating opportunities for climate-vulnerable communities.

The rights and well-being of these inherently vulnerable individuals deserve priority from the authorities. They must actively engage with foreign embassies to safeguard our migrant workers and ensure they are not subjected to exploitation. Also, the authorities must better regulate migration costs and crack down on unscrupulous recruitment agencies preying on desperate job seekers. Over the years, countless workers have faced abuse while abroad, many even losing their lives. This, too, needs to change. The government must take decisive action to address these interlinked issues and uphold the rights of our migrant workers.