- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #41

Saif

Senior Member

- Messages

- 15,242

- Reaction score

- 7,802

- Origin

- Residence

- Axis Group

‘Protesters are not given medical care here’

How a July warrior was denied immediate medical care.

Ordeals of a July uprising warrior

‘Protesters are not given medical care here’

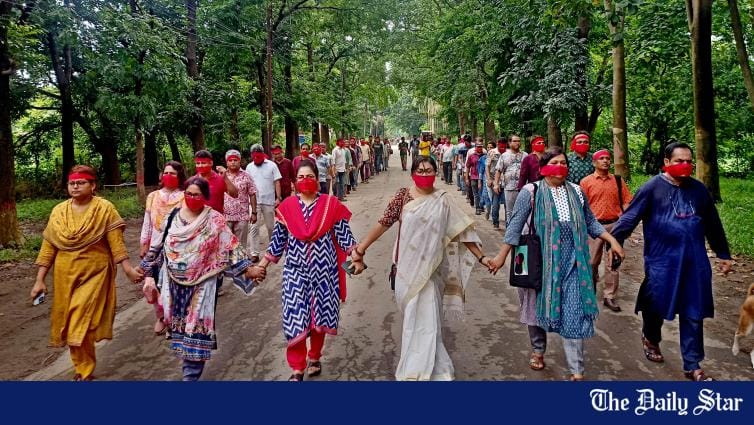

July 15, 2024 photo at DU

On July 15, 2024, Chhatra League hooligans and hired miscreants swooped down on protesters with iron rods, machetes, hockey sticks, and other weapons at the Dhaka University campus, injuring many, including Sokal. FILE PHOTO: RASHED SUMON

Sinthia Mehrin Sokal hails from a rural area in Sunamganj. She passed all pre-university exams with flying colours and began majoring in Criminology at Dhaka University (DU) in the 2020-21 academic year. For years, she was the only student from her village to qualify to study at this university.

Sokal had no political party affiliation. However, soon after coming to DU and becoming a resident student of Ruqayyah Hall, she started feeling the heat of the political crises that gripped Bangladesh and its universities during Sheikh Hasina's misrule.

In university dormitories, students were forced to endure Chhatra League's mistreatment. Predicaments of resident female students were much worse, which remained largely underreported. Sokal came to know about female students who were sexually abused by Chhatra League members.

The reinstatement of the quota system in government jobs in June 2024 rang the death knell for Sokal's future. She became active in the Students Against Discrimination movement.

On July 14, 2024, Sokal joined students' protest march to Bangabhaban to press home their demand that 95 percent of jobs be awarded based on merit. On that day, Sheikh Hasina had the audacity to use the pejorative term "razakar" to discredit the student movement. Immediately, students around the country burst into anger and took to the streets. That night, Sokal and other students broke the locks of the main gate and marched out of Ruqayyah Hall to demonstrate.

On July 15, 2024, Sokal took to the streets with her friends. When their procession came to the university's VC Chattor (square), Chhatra League hooligans and hired miscreants swooped down on it and started attacking protesters with iron rods, machetes, hockey sticks, and other weapons. One thug hit Sokal very hard and wedged a dent on her head. She fell on the ground and remained unconscious for the next two and a half hours of which she has no memory at all. She was taken to Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH).

Chhatra League ruffians made several attempts to enter DMCH to attack injured protesters, but each time were resisted by brave healthcare providers. Then they pretended to be injured patients and thus entered DMCH and brutally assaulted the protesters taking medical care.

Feeling vulnerable to further attacks, Sokal left DMCH with the help of a relative but without proper treatment. On the way to Universal Medical College and Hospital in Mohakhali, she kept vomiting and had a near-death experience. The doctor recommended CT-scan and hospital admission, which Sokal couldn't afford. At her sister's house in Mohakhali, Sokal continued vomiting and feared the worst. Her otherwise mentally strong sister advised Sokal to bathe and prepare for death.

The CT-scan report showed that the head injury was deep and her skull was fractured.

Meanwhile, protest marches continued, defying Hasina's repression. Dhaka turned into a war zone, as the government imposed a curfew in the city.

Sokal's sister managed to take her to the city's Impulse Hospital. As she had not received proper early intervention, her infections spread and she was operated on immediately. It took two hours for the doctors to clean the infections and dress her head. Each episode of dressing caused her excruciating pain.

That was not the end of Sokal's ordeal.

The Hasina government shut down the Internet. From her sister's house, Sokal heard sounds of shootings and airstrikes from helicopters that killed many young people. The police were conducting block raids and barging into people's houses to round up protesters or anyone who looked like students. Sokal couldn't sleep at night and was having nightmares worrying that the police might come anytime and arrest her.

In the meantime, Sokal's mother fell seriously ill back home, and none of her siblings were available to take the ailing mother to hospital. She rushed to Mymensingh—the nearest town from her village—to arrange for her mother's treatment. The situation in Mymensingh was also very precarious. The police were herding students like felons and sending them to jail.

While Sokal was running here and there for her mother's treatment with her visible head injury, she kept being asked: "Did you participate in the movement?" Unbearable pain, anxiety about her mother's condition and the fear of being arrested by the police—all these made Sokal's life in Mymensingh intolerable.

On July 27, 2024, one day before the scheduled date of her head dressing, Sokal went to a hospital in Mymensingh for a doctor's consultation hoping that her head wound would be dressed the next day. The doctor wanted to know the reason for her medical condition. She bluntly said, "I participated in the quota reform movement."

The doctor made a sharp reply: "Protesters are not given medical care here." Sokal left the hospital stunned and dumbfounded. She dreaded that many other July warriors might have faced similar cruelty and embraced martyrdom due to lack of medical care.

The next day, Sokal had her head wound dressed at Mymensingh Medical College Hospital, where the duty doctor whispered to her: "Don't tell anyone that you are a protester." Once she was discharged and the effect of anaesthesia had worn off, she started experiencing acute, paroxysmal pain.

On August 1, 2024, Sokal went to her village in Dharmapasha, Sunamganj, with her mother and faced hostility from Awami League-leaning villagers. Using sexist terms, they called her names for her involvement in demonstrations.

But Sokal was unstoppable.

Mobilising and organising other students, she planned a rally in the village on August 4, 2024. Local Awami League affiliates passed their details to the police and started threatening them. Fear gripped Sokal, as she was having terrible pain in her head, her father had a heart condition, and her mother had undergone an operation only two days ago. What would happen to her parents if she were arrested!

Then came August 5, 2024, and the news of Hasina's fall and flight to India. People around the country took to the streets and joined spontaneous processions of joy, sharing sweetmeats with each other. Sokal participated in a similar procession in her village and felt gratified that her suffering and the lives and blood of thousands of young people didn't go in vain. The country became free from Hasina's mafia-style autocracy.

But Sokal's ordeal continues. She still suffers from occasional short-term memory loss and has to have regular medical check-ups. She has to move and walk carefully. But she is grateful to the Almighty for giving her an extra life.

She is a living martyr.

There are many more Sokals, and we owe them a debt of gratitude.

Dr Md Mahmudul Hasan is professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the International Islamic University Malaysia.

‘Protesters are not given medical care here’

July 15, 2024 photo at DU

On July 15, 2024, Chhatra League hooligans and hired miscreants swooped down on protesters with iron rods, machetes, hockey sticks, and other weapons at the Dhaka University campus, injuring many, including Sokal. FILE PHOTO: RASHED SUMON

Sinthia Mehrin Sokal hails from a rural area in Sunamganj. She passed all pre-university exams with flying colours and began majoring in Criminology at Dhaka University (DU) in the 2020-21 academic year. For years, she was the only student from her village to qualify to study at this university.

Sokal had no political party affiliation. However, soon after coming to DU and becoming a resident student of Ruqayyah Hall, she started feeling the heat of the political crises that gripped Bangladesh and its universities during Sheikh Hasina's misrule.

In university dormitories, students were forced to endure Chhatra League's mistreatment. Predicaments of resident female students were much worse, which remained largely underreported. Sokal came to know about female students who were sexually abused by Chhatra League members.

The reinstatement of the quota system in government jobs in June 2024 rang the death knell for Sokal's future. She became active in the Students Against Discrimination movement.

On July 14, 2024, Sokal joined students' protest march to Bangabhaban to press home their demand that 95 percent of jobs be awarded based on merit. On that day, Sheikh Hasina had the audacity to use the pejorative term "razakar" to discredit the student movement. Immediately, students around the country burst into anger and took to the streets. That night, Sokal and other students broke the locks of the main gate and marched out of Ruqayyah Hall to demonstrate.

On July 15, 2024, Sokal took to the streets with her friends. When their procession came to the university's VC Chattor (square), Chhatra League hooligans and hired miscreants swooped down on it and started attacking protesters with iron rods, machetes, hockey sticks, and other weapons. One thug hit Sokal very hard and wedged a dent on her head. She fell on the ground and remained unconscious for the next two and a half hours of which she has no memory at all. She was taken to Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH).

Chhatra League ruffians made several attempts to enter DMCH to attack injured protesters, but each time were resisted by brave healthcare providers. Then they pretended to be injured patients and thus entered DMCH and brutally assaulted the protesters taking medical care.

Feeling vulnerable to further attacks, Sokal left DMCH with the help of a relative but without proper treatment. On the way to Universal Medical College and Hospital in Mohakhali, she kept vomiting and had a near-death experience. The doctor recommended CT-scan and hospital admission, which Sokal couldn't afford. At her sister's house in Mohakhali, Sokal continued vomiting and feared the worst. Her otherwise mentally strong sister advised Sokal to bathe and prepare for death.

The CT-scan report showed that the head injury was deep and her skull was fractured.

Meanwhile, protest marches continued, defying Hasina's repression. Dhaka turned into a war zone, as the government imposed a curfew in the city.

Sokal's sister managed to take her to the city's Impulse Hospital. As she had not received proper early intervention, her infections spread and she was operated on immediately. It took two hours for the doctors to clean the infections and dress her head. Each episode of dressing caused her excruciating pain.

That was not the end of Sokal's ordeal.

The Hasina government shut down the Internet. From her sister's house, Sokal heard sounds of shootings and airstrikes from helicopters that killed many young people. The police were conducting block raids and barging into people's houses to round up protesters or anyone who looked like students. Sokal couldn't sleep at night and was having nightmares worrying that the police might come anytime and arrest her.

In the meantime, Sokal's mother fell seriously ill back home, and none of her siblings were available to take the ailing mother to hospital. She rushed to Mymensingh—the nearest town from her village—to arrange for her mother's treatment. The situation in Mymensingh was also very precarious. The police were herding students like felons and sending them to jail.

While Sokal was running here and there for her mother's treatment with her visible head injury, she kept being asked: "Did you participate in the movement?" Unbearable pain, anxiety about her mother's condition and the fear of being arrested by the police—all these made Sokal's life in Mymensingh intolerable.

On July 27, 2024, one day before the scheduled date of her head dressing, Sokal went to a hospital in Mymensingh for a doctor's consultation hoping that her head wound would be dressed the next day. The doctor wanted to know the reason for her medical condition. She bluntly said, "I participated in the quota reform movement."

The doctor made a sharp reply: "Protesters are not given medical care here." Sokal left the hospital stunned and dumbfounded. She dreaded that many other July warriors might have faced similar cruelty and embraced martyrdom due to lack of medical care.

The next day, Sokal had her head wound dressed at Mymensingh Medical College Hospital, where the duty doctor whispered to her: "Don't tell anyone that you are a protester." Once she was discharged and the effect of anaesthesia had worn off, she started experiencing acute, paroxysmal pain.

On August 1, 2024, Sokal went to her village in Dharmapasha, Sunamganj, with her mother and faced hostility from Awami League-leaning villagers. Using sexist terms, they called her names for her involvement in demonstrations.

But Sokal was unstoppable.

Mobilising and organising other students, she planned a rally in the village on August 4, 2024. Local Awami League affiliates passed their details to the police and started threatening them. Fear gripped Sokal, as she was having terrible pain in her head, her father had a heart condition, and her mother had undergone an operation only two days ago. What would happen to her parents if she were arrested!

Then came August 5, 2024, and the news of Hasina's fall and flight to India. People around the country took to the streets and joined spontaneous processions of joy, sharing sweetmeats with each other. Sokal participated in a similar procession in her village and felt gratified that her suffering and the lives and blood of thousands of young people didn't go in vain. The country became free from Hasina's mafia-style autocracy.

But Sokal's ordeal continues. She still suffers from occasional short-term memory loss and has to have regular medical check-ups. She has to move and walk carefully. But she is grateful to the Almighty for giving her an extra life.

She is a living martyr.

There are many more Sokals, and we owe them a debt of gratitude.

Dr Md Mahmudul Hasan is professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the International Islamic University Malaysia.