Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,117

- Likes

- 8,060

- Nation

- Axis Group

Mujibnagar Govt members, including Bangabandhu, Tajuddin ‘valiant freedom fighters’, others are ‘associates’

The Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs issued the amended Jatiya Muktijoddha Council (Jamuka) Ordinance on Tuesday night, changing the definition of freedom fighter.

Mujibnagar Govt members, including Bangabandhu, Tajuddin ‘valiant freedom fighters’, others are ‘associates’

The adviser said that the ordinance cancels nobody’s status. It only redefines the terms.

Staff CorrespondentDhaka

Updated: 04 Jun 2025, 14: 52

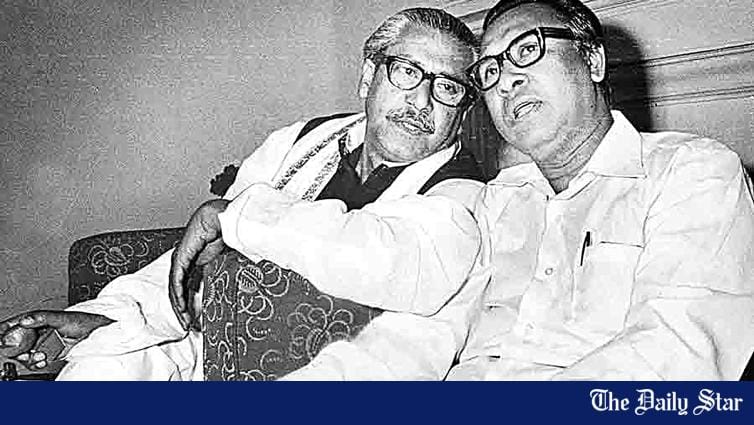

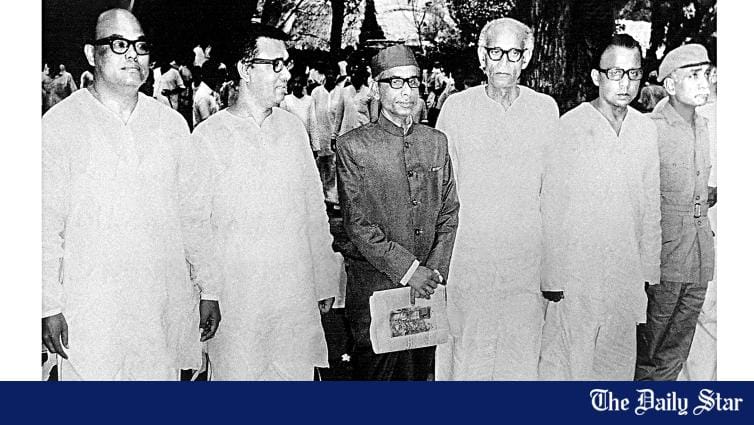

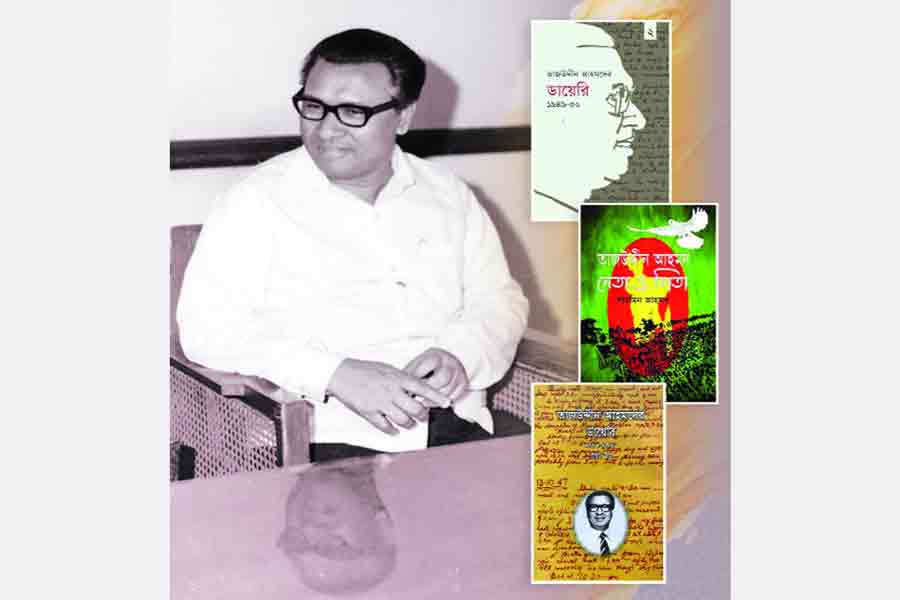

Mujibnagar Government members including Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmed are ‘valiant freedom fighters’, while others are ‘associates’.

The members of the Mujibnagar Government, which was formed on 10 April 1971, during the great liberation war, will be recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters,’ while people who assisted in the formation of the Mujibnagar Government will be considered ‘associates of the liberation war.’

The Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs issued the amended Jatiya Muktijoddha Council (Jamuka) Ordinance on Tuesday night, changing the definition of freedom fighter.

The first government of independent Bangladesh (Mujibnagar Government) took oath on 17 April 1971. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was declared the president. Syed Nazrul Islam was appointed vice president.

Since Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was imprisoned in a Pakistani jail, Syed Nazrul Islam served as acting president. Tajuddin Ahmad was appointed as prime minister, M Mansur Ali as finance minister, AHM Qamaruzzaman as home minister, and Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad as foreign minister.

According to the new ordinance, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman along with the four national leaders, will be recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’, the interim government’s liberation war affairs ministry adviser Faruk-e-Azam told Prothom Alo.

He said all those who were part of Mujibnagar Government are freedom fighters. However, the officials and employees of the Mujibnagar Government will be considered ‘associates of Liberation War.’

Faruk-e-Azam further said that it was found that some employees of the Mujibnagar Government have been recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’ during the verification of the list of freedom fighters. From now on, they will be the ‘associates of Liberation War.’

The adviser said that the ordinance cancels nobody’s status. It only redefines the terms. Those who are currently receiving benefits will continue to do so. Only those who directly fought on the battlefield will be called ‘valiant freedom fighters,’ and others will be the “associates of Liberation War.”

In the ordinance, the government has set five categories to identify the associates of the freedom fighters

The categories are: one, the professionals who stayed abroad and contributed to the liberation war and the Bangladeshi citizens who played an active role in mobilising the global opinions; two, the people who worked as officials and employees of the Government of Bangladesh (Mujibnagar government) formed during the liberation war, physicians, nurses and other assistants employed by the Mujibnagar government; three, all the MNAs and MPAs who were involved with the Government of Bangladesh (Mujibnagar government) formed during the liberation war, and later regarded as members of the constituent assembly; four, all the artistes and crew members of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra and all the Bangladeshi journalists in and outside of the country who played role in favour of the liberation war; five, Swadhin Bangla Football Team.

According to Ministry of Liberation War Affairs, the 21 members of Shadhin Bangla Football Team were previously recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’. Notable among them are Mohammad Zakaria Pintoo, Kazi Salahuddin, and Enayetur Rahman Khan. From now on, they will be recognised as ‘associates of Liberation War.’

The new definition of the freedom fighter says, the civilians (who were above the minimum age limit set by the government), who took preparation and training for the war inside the country between 26 March and 16 December of 1971 and, the civilians, who crossed the boundary and included their names at various training camps in India and fought in the war against occupied Pakistani forces and their local collaborators - Rajakar, Al Badr, Al Shams, the then Jamaat-e-Islami, Nejam-e-Islam, and Peace Committee members, will be considered as freedom fighters.

Along with them, members of the armed forces, East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), the police, Muktibahini, the government-in-exile and the other forces recognised by that government like naval commandos, Kilo Force and Ansar will be included as freedom fighters.

According to the new definition, all the women tortured by the occupied Pakistani forces and their collaborators will also be included as freedom fighters. Apart from them, all the physicians and nurses and their assistants who gave medical treatment to the injured freedom fighters at Field Hospitals will be regarded as freedom fighters.

The adviser said that the ordinance cancels nobody’s status. It only redefines the terms.

Staff CorrespondentDhaka

Updated: 04 Jun 2025, 14: 52

Mujibnagar Government members including Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmed are ‘valiant freedom fighters’, while others are ‘associates’.

The members of the Mujibnagar Government, which was formed on 10 April 1971, during the great liberation war, will be recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters,’ while people who assisted in the formation of the Mujibnagar Government will be considered ‘associates of the liberation war.’

The Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs issued the amended Jatiya Muktijoddha Council (Jamuka) Ordinance on Tuesday night, changing the definition of freedom fighter.

The first government of independent Bangladesh (Mujibnagar Government) took oath on 17 April 1971. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was declared the president. Syed Nazrul Islam was appointed vice president.

Since Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was imprisoned in a Pakistani jail, Syed Nazrul Islam served as acting president. Tajuddin Ahmad was appointed as prime minister, M Mansur Ali as finance minister, AHM Qamaruzzaman as home minister, and Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad as foreign minister.

According to the new ordinance, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman along with the four national leaders, will be recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’, the interim government’s liberation war affairs ministry adviser Faruk-e-Azam told Prothom Alo.

He said all those who were part of Mujibnagar Government are freedom fighters. However, the officials and employees of the Mujibnagar Government will be considered ‘associates of Liberation War.’

Faruk-e-Azam further said that it was found that some employees of the Mujibnagar Government have been recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’ during the verification of the list of freedom fighters. From now on, they will be the ‘associates of Liberation War.’

The adviser said that the ordinance cancels nobody’s status. It only redefines the terms. Those who are currently receiving benefits will continue to do so. Only those who directly fought on the battlefield will be called ‘valiant freedom fighters,’ and others will be the “associates of Liberation War.”

In the ordinance, the government has set five categories to identify the associates of the freedom fighters

The categories are: one, the professionals who stayed abroad and contributed to the liberation war and the Bangladeshi citizens who played an active role in mobilising the global opinions; two, the people who worked as officials and employees of the Government of Bangladesh (Mujibnagar government) formed during the liberation war, physicians, nurses and other assistants employed by the Mujibnagar government; three, all the MNAs and MPAs who were involved with the Government of Bangladesh (Mujibnagar government) formed during the liberation war, and later regarded as members of the constituent assembly; four, all the artistes and crew members of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra and all the Bangladeshi journalists in and outside of the country who played role in favour of the liberation war; five, Swadhin Bangla Football Team.

According to Ministry of Liberation War Affairs, the 21 members of Shadhin Bangla Football Team were previously recognised as ‘valiant freedom fighters’. Notable among them are Mohammad Zakaria Pintoo, Kazi Salahuddin, and Enayetur Rahman Khan. From now on, they will be recognised as ‘associates of Liberation War.’

The new definition of the freedom fighter says, the civilians (who were above the minimum age limit set by the government), who took preparation and training for the war inside the country between 26 March and 16 December of 1971 and, the civilians, who crossed the boundary and included their names at various training camps in India and fought in the war against occupied Pakistani forces and their local collaborators - Rajakar, Al Badr, Al Shams, the then Jamaat-e-Islami, Nejam-e-Islam, and Peace Committee members, will be considered as freedom fighters.

Along with them, members of the armed forces, East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), the police, Muktibahini, the government-in-exile and the other forces recognised by that government like naval commandos, Kilo Force and Ansar will be included as freedom fighters.

According to the new definition, all the women tortured by the occupied Pakistani forces and their collaborators will also be included as freedom fighters. Apart from them, all the physicians and nurses and their assistants who gave medical treatment to the injured freedom fighters at Field Hospitals will be regarded as freedom fighters.