Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,262

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Four journos of a newspaper injured in attack

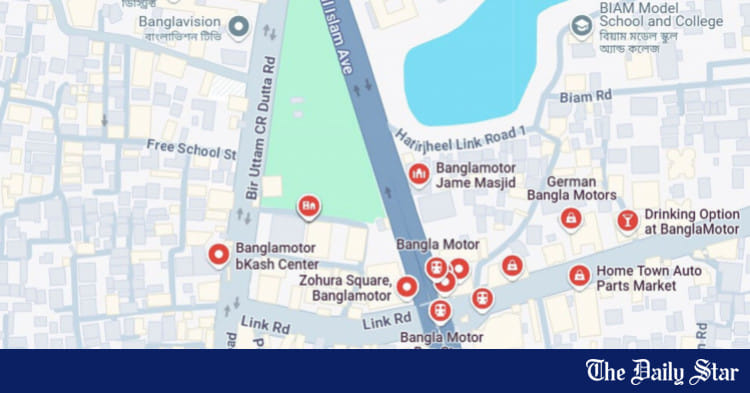

Four journalists, including the editor and managing editor of the Janabani newspaper, were injured in an attack by criminals near their office in the capital's Banglamotor area yesterday afternoon.

Four journos of a newspaper injured in attack

Four journalists, including the editor and managing editor of the Janabani newspaper, were injured in an attack by criminals near their office in the capital's Banglamotor area yesterday afternoon.

The incident took place around 4:30pm when the journalists were on their way to the office.

The injured include Shafiqul Islam, editor and publisher of Janabani, Managing Editor Raju Ahmed Shah, Special Correspondent Bashir Hossain Khan, and online editor Ataur Hossain.

According to Bashir Hossain, a group of 20-22 men ambushed them.

"At first, we could not comprehend the situation. It appeared to be a pre-planned attack. We did not recognise any of them," he said.

He further mentioned that earlier a person named Ramzan had come to the Janabani office and threatened the staff.

The attackers reportedly first inquired about their names before launching the assault. "The way they came at us suggested that someone had directed them to attack us," Bashir added.

The journalists were taken to the emergency department of Dhaka Medical College Hospital around 6:00pm. They received treatment for their injuries and were later discharged.

Four journalists, including the editor and managing editor of the Janabani newspaper, were injured in an attack by criminals near their office in the capital's Banglamotor area yesterday afternoon.

The incident took place around 4:30pm when the journalists were on their way to the office.

The injured include Shafiqul Islam, editor and publisher of Janabani, Managing Editor Raju Ahmed Shah, Special Correspondent Bashir Hossain Khan, and online editor Ataur Hossain.

According to Bashir Hossain, a group of 20-22 men ambushed them.

"At first, we could not comprehend the situation. It appeared to be a pre-planned attack. We did not recognise any of them," he said.

He further mentioned that earlier a person named Ramzan had come to the Janabani office and threatened the staff.

The attackers reportedly first inquired about their names before launching the assault. "The way they came at us suggested that someone had directed them to attack us," Bashir added.

The journalists were taken to the emergency department of Dhaka Medical College Hospital around 6:00pm. They received treatment for their injuries and were later discharged.