- Copy to clipboard

- Thread starter

- #436

Saif

Senior Member

- Jan 24, 2024

- 11,682

- 6,563

- Origin

- Residence

- Axis Group

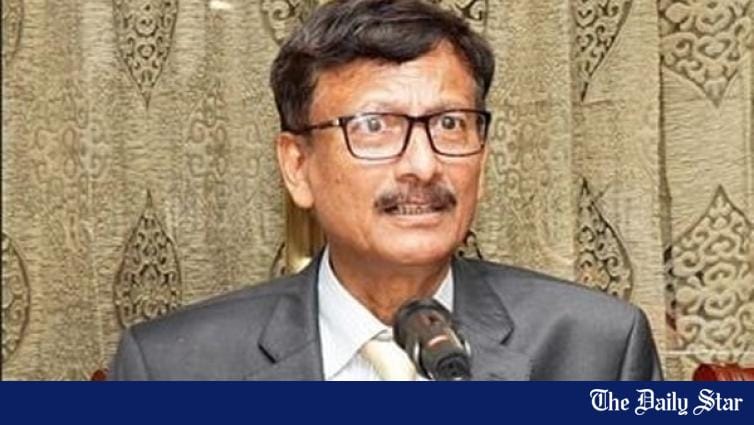

Dhaka committed to boosting Indian Ocean partnership: foreign adviser

The foreign adviser said the Indian Ocean region is a crucial strategic area that links the Asia-Pacific and African regions, with profound economic, political and security significance

Dhaka committed to boosting Indian Ocean partnership: foreign adviser

Md Touhid Hossain. File photo

Bangladesh has reiterated its commitment to embracing the tremendous opportunities that the Indian Ocean region offers by strengthening partnerships.

"We are committed to strengthening our partnerships across the Indian Ocean, addressing emerging challenges, and embracing the tremendous opportunities this region offers," said Foreign Affairs Adviser Md Touhid Hossain today.

The multiple challenges and other geo-economic and geo-strategic factors require increased cooperation among the States, he said.

Hossain made the remarks while speaking at the plenary session titled "Strengthening Maritime Supply Chains: Overcoming Disruptions and Enhancing Resilience" as part of the 8th Indian Ocean Conference (IOC)-2025 in Muscat, Oman.

Sheikh Humaid Al Maani, Head of the Diplomatic Academy, MoFA, Oman chaired the session.

The foreign adviser said the Indian Ocean region is a crucial strategic area that links the Asia-Pacific and African regions, with profound economic, political and security significance.

The conference provided a platform for participants to engage in "constructive discussions, share ideas, exchange knowledge, identify actionable solutions, and build meaningful partnerships and cooperation" in the region.

"We look forward to working together to ensure a brighter, more prosperous future for all nations of the Indian Ocean and beyond," Adviser Touhid said.

As a littoral state, he said, Bangladesh has long been a centre of maritime activities and it actively participates in various regional platforms, including the Indian Ocean Rim Association and the International Seabed Authority.

The 8th Indian Ocean Conference is being held under the theme "Voyage of New Horizons of Maritime Partnership."

He said Bangladesh places strong importance on maritime cooperation for facilitating the efficient movement of goods, services and people and for advancing food security, energy security, water cooperation, disaster risk reduction and providing fair access to global public goods. Bangladesh advocates for "shared prosperity" through "shared responsibility".

Maritime transport is the main artery of global trade and maritime supply chains remain the backbone of the global economy, he added.

He said eighty percent of global trade by volume, and over seventy percent by value, is transported by sea and the Indian Ocean, the world's third-largest body of water, plays a crucial role in this global trade.

Approximately 80 percent of the world's seaborne oil trade transits through the strategic choke points of the Indian Ocean, making it a vital link between the East and the West.

"Countries depend on the Indian Ocean for the movement of goods through maritime trade routes, safeguarding their economic and energy interests. However, the sector is facing multifaceted challenges that endanger the efficiency, reliability, resilience and sustainability of maritime supply chains," he said.

Maritime supply chain is vulnerable to many challenges like port congestion, capacity limitations, regulatory, operational and administrative issues, cyberattacks, piracy, and geopolitical tensions, which can disrupt the efficiency of maritime supply chains.

"We must also remember that the oceans are not only a driving force for global economic growth but also a vital source of food security," Hossain said.

The oceans are facing growing pressures from population growth, global competition for resources, rising food demand, water scarcity, maritime security threats, climate change, biodiversity loss and marine pollution.

"We need to take appropriate actions to tackle the maritime security threats of piracy, armed robbery, human trafficking, illegal arms trade, and illegal and unregulated fishing, among others. We need to address regulatory and administrative issues," said the foreign adviser.

The global economy, food security, and energy supplies are at increasing risk due to vulnerabilities at key maritime routes, he noted.

"We must take measures to address vulnerabilities and enhance resilience," he said

Strengthening maritime supply chains involves a holistic approach combining technology, infrastructure improvements, strategic planning, risk management strategies and cross-border collaboration.

"We need to facilitate maritime connectivity, reduce the trade barriers," he said, adding that they also need to consider liberalisation of the visa regime, particularly easing visas and other administrative processes for the seafarers, ensuring facilities for them, as their roles are crucial in maintaining the maritime supply chain.

He said the Indian Ocean has historically been a region of great collaboration.

"The benefits of multilateral cooperation in maritime issues are likely to increase over time," Touhid said, adding that to ensure a resilient and improved shared future, it is essential for the countries in the Indian Ocean region to explore opportunities for mutual collaboration across all possible areas.

Each coastal nation should ensure that growth and prosperity in the Indian Ocean region, as well as the surrounding seas and bays, are built on mutual trust, respect.

All nations should understand the idea of equal interests, as all littoral states collaborate to develop together, he added.

"We also must prioritise conservation and the sustainable use of ocean and coastal resources to ensure that the use of these resources does not contribute to the decline in the health of oceanic and coastal environments," the foreign adviser said.

Md Touhid Hossain. File photo

Bangladesh has reiterated its commitment to embracing the tremendous opportunities that the Indian Ocean region offers by strengthening partnerships.

"We are committed to strengthening our partnerships across the Indian Ocean, addressing emerging challenges, and embracing the tremendous opportunities this region offers," said Foreign Affairs Adviser Md Touhid Hossain today.

The multiple challenges and other geo-economic and geo-strategic factors require increased cooperation among the States, he said.

Hossain made the remarks while speaking at the plenary session titled "Strengthening Maritime Supply Chains: Overcoming Disruptions and Enhancing Resilience" as part of the 8th Indian Ocean Conference (IOC)-2025 in Muscat, Oman.

Sheikh Humaid Al Maani, Head of the Diplomatic Academy, MoFA, Oman chaired the session.

The foreign adviser said the Indian Ocean region is a crucial strategic area that links the Asia-Pacific and African regions, with profound economic, political and security significance.

The conference provided a platform for participants to engage in "constructive discussions, share ideas, exchange knowledge, identify actionable solutions, and build meaningful partnerships and cooperation" in the region.

"We look forward to working together to ensure a brighter, more prosperous future for all nations of the Indian Ocean and beyond," Adviser Touhid said.

As a littoral state, he said, Bangladesh has long been a centre of maritime activities and it actively participates in various regional platforms, including the Indian Ocean Rim Association and the International Seabed Authority.

The 8th Indian Ocean Conference is being held under the theme "Voyage of New Horizons of Maritime Partnership."

He said Bangladesh places strong importance on maritime cooperation for facilitating the efficient movement of goods, services and people and for advancing food security, energy security, water cooperation, disaster risk reduction and providing fair access to global public goods. Bangladesh advocates for "shared prosperity" through "shared responsibility".

Maritime transport is the main artery of global trade and maritime supply chains remain the backbone of the global economy, he added.

He said eighty percent of global trade by volume, and over seventy percent by value, is transported by sea and the Indian Ocean, the world's third-largest body of water, plays a crucial role in this global trade.

Approximately 80 percent of the world's seaborne oil trade transits through the strategic choke points of the Indian Ocean, making it a vital link between the East and the West.

"Countries depend on the Indian Ocean for the movement of goods through maritime trade routes, safeguarding their economic and energy interests. However, the sector is facing multifaceted challenges that endanger the efficiency, reliability, resilience and sustainability of maritime supply chains," he said.

Maritime supply chain is vulnerable to many challenges like port congestion, capacity limitations, regulatory, operational and administrative issues, cyberattacks, piracy, and geopolitical tensions, which can disrupt the efficiency of maritime supply chains.

"We must also remember that the oceans are not only a driving force for global economic growth but also a vital source of food security," Hossain said.

The oceans are facing growing pressures from population growth, global competition for resources, rising food demand, water scarcity, maritime security threats, climate change, biodiversity loss and marine pollution.

"We need to take appropriate actions to tackle the maritime security threats of piracy, armed robbery, human trafficking, illegal arms trade, and illegal and unregulated fishing, among others. We need to address regulatory and administrative issues," said the foreign adviser.

The global economy, food security, and energy supplies are at increasing risk due to vulnerabilities at key maritime routes, he noted.

"We must take measures to address vulnerabilities and enhance resilience," he said

Strengthening maritime supply chains involves a holistic approach combining technology, infrastructure improvements, strategic planning, risk management strategies and cross-border collaboration.

"We need to facilitate maritime connectivity, reduce the trade barriers," he said, adding that they also need to consider liberalisation of the visa regime, particularly easing visas and other administrative processes for the seafarers, ensuring facilities for them, as their roles are crucial in maintaining the maritime supply chain.

He said the Indian Ocean has historically been a region of great collaboration.

"The benefits of multilateral cooperation in maritime issues are likely to increase over time," Touhid said, adding that to ensure a resilient and improved shared future, it is essential for the countries in the Indian Ocean region to explore opportunities for mutual collaboration across all possible areas.

Each coastal nation should ensure that growth and prosperity in the Indian Ocean region, as well as the surrounding seas and bays, are built on mutual trust, respect.

All nations should understand the idea of equal interests, as all littoral states collaborate to develop together, he added.

"We also must prioritise conservation and the sustainable use of ocean and coastal resources to ensure that the use of these resources does not contribute to the decline in the health of oceanic and coastal environments," the foreign adviser said.