Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,300

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Potato Paradox: Just another curry on the rice plate? This will not solve the price problem

Punishing retail prices during low output and throwaway rates during bumper harvests have become a familiar cycle for potato farmers. The swings are recurring and costly, leaving as many as half a crore growers exposed to debt in good years and public anger in bad ones.

Potato Paradox: Just another curry on the rice plate? This will not solve the price problem

Punishing retail prices during low output and throwaway rates during bumper harvests have become a familiar cycle for potato farmers. The swings are recurring and costly, leaving as many as half a crore growers exposed to debt in good years and public anger in bad ones.

Yet agri experts and supply chain players say the problem has little to do with farmers, or even with production. Instead, it reflects how potatoes are treated in policy and planning.

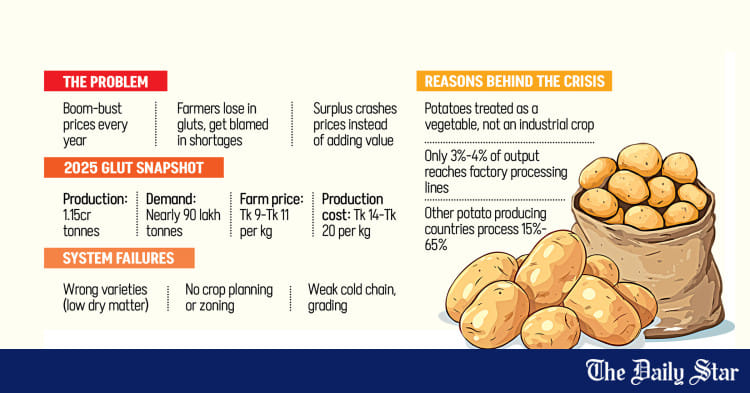

Unlike many other countries, Bangladesh largely views the crop as just another vegetable eaten with rice, not as a basic industrial raw material.

That distinction matters. When production overshoots domestic demand, prices collapse. Farmers absorb the losses, while the economy misses out on value addition that could stabilise incomes and absorb surplus output.

Bangladesh is the world's seventh-largest potato producer. Still, it remains far behind global peers in industrial use of the tuber.

In China, about 15 percent of potato output goes into industrial processing. In the Netherlands, Germany, France and the United States, the share ranges from 60 percent to 65 percent. Russia and Ukraine process 20 percent to 30 percent, while neighbouring India, with similar food habits, uses 5 percent to 7 percent.

Bangladesh, by contrast, processes only 3 percent to 4 percent of its total output, according to industry insiders.

The difference is decisive. In countries where potatoes feed factories, surplus strengthens supply chains. In Bangladesh, surplus simply crashes prices.

After rice, potatoes are the second most produced crop in Bangladesh and a pillar of food security. Yet more than a quarter of output is lost after harvest, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, which points to weak storage, handling and processing capacity.

WRONG VARIETIES, WEAK PLANNING

Kamruzzaman Kamal, marketing director of Pran-RFL Group, the parent of the local agro processing giant Pran, said industrial processing is limited because most locally grown potatoes are table varieties, not processing-grade crops.

"These potatoes have high moisture and sugar content, which makes them unsuitable for products like French fries. They lose colour and become soft after frying," said Kamal.

Globally, potatoes used for fries, chips and flakes require dry matter of around 22.5 percent. But locally grown potatoes usually contain only 16 percent to 19 percent dry matter, according to scientists.

While potatoes are locally used at home to make chips, and in factories to produce crackers, biscuits and chanachur, the backward linkage industry for flakes and starch is still underdeveloped. Only one or two such factories are currently in production.

Kamal said farmers are not encouraged to grow processing varieties because crop planning is mostly individual-driven rather than coordinated. Many existing varieties are disease-prone, poorly adapted to climate stress and quick to spoil.

Inadequate storage, no grading and sorting at farm level, insufficient cold-chain infrastructure and limited warehousing have further constrained both industrial use and exports, added the Pran-RFL marketing director.

Khurshid Ahmad Farhad, general manager for international business and corporate affairs at Bombay Sweets and Company Limited, a popular food processing brand, said the absence of integrated crop planning and unpredictable weather has kept industrial processing from reaching scale.

Factories producing flakes, slices, chips and biscuits need potatoes of specific size and quality. Bangladesh does not produce enough of these at consistent volumes, he said. Even when quality potatoes are available, production costs are often far higher than international benchmarks, making local products uncompetitive.

"In recent times, costs have risen so sharply that a Dubai-based trader told me they could supply potato flakes at a lower price than we can," Farhad said.

Globally, the largest potato-based industrial products include mashed potatoes and French fries. In Bangladesh, suitable varieties have yet to be developed at a commercial scale, leaving much of the segment untapped.

Although government agencies hold relevant crop data, it is neither centrally coordinated nor used for forecasting, Farhad said. As a result, annual output swings widely between about 80 lakh tonnes and nearly 90 lakh tonnes, with no early warning for the industry.

"This uncertainty is the biggest obstacle. Planning depends on assured availability and consistent quality of raw materials," he said.

THE GLUT, THEN THE CRASH

Strong prices in the 2024 season encouraged farmers to expand potato acreage massively this year in the hope of better returns. Instead, excessive output triggered a severe glut and eventual price fall.

According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, potato production reached a record 1.15 crore tonnes last season, far above annual domestic demand of around 90 lakh tonnes.

Cultivated area rose 8 percent year-on-year to 4.92 lakh hectares in fiscal year 2024-25, while output increased 9 percent from 1.06 crore tonnes the previous year.

The oversupply sent field-level prices tumbling to Tk 9 to Tk 11 per kg, well below the estimated average production cost of Tk 14. In northern regions, costs were higher, at around Tk 20 per kg, according to the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE).

For farmers, the result was debt rather than profit. For the economy, it was another missed chance to channel surplus into value-added uses.

'TYPICAL COLD STORAGE ONLY DELAYS LOSSES'

Bangladesh has expanded cold storage capacity to about 35-40 lakh tonnes. Processing capacity, however, is remarkably low.

Md Mohsin Ali, head of supply chain at Quasem Industries Limited, which produces Sun Chips, said processing capacity stands at just 70,000-80,000 tonnes.

The shortage of modern cold storage designed for processing-grade potatoes is one of the sector's biggest constraints, he said. "Therefore, typical cold storage facilities currently delay losses. It does not create value," he said. "Without factories that can absorb surplus, price crashes will continue."

In many countries, he said, potatoes are a staple food and a major industrial input. In Bangladesh, those consumption patterns and industrial linkages have yet to emerge.

According to Ali, weak policy support, lack of dedicated processing policies and limited investment in research and development are major barriers.

DEMAND EXISTS, QUALITY DOES NOT

Apart from the unavailability of commercial-grade potatoes, the shortage of premium-grade crops is visible even in high-end kitchens.

Md Ershad Ali, assistant sous chef at Pan Pacific Sonargaon Dhaka, a five-star hotel, said they serve potatoes to their guests at every meal, with each buffet offering at least one potato dish.

Some international recipes, however, cannot be prepared with local potatoes due to inconsistent size and grading. Overseas, potatoes arrive uniformly graded and ready for consistent cuts and presentation. Local supplies vary widely.

The hotel uses about 500 kg of potatoes each week. That could rise to 800 kg if uniformly graded, high-quality potatoes were available, he said.

A POLICY BLIND SPOT

FH Ansary, managing director of ACI Agribusiness, said potatoes need to be viewed through four lenses: food, industry, environment and health.

"We treat potatoes as just a vegetable. Elsewhere, they are protein sources, pharmaceutical inputs, packaging material and industrial feedstock," he said.

Ansary said farmers focus on table potatoes because the market is guaranteed. Seeds of processing varieties are scarce, quality-based cultivation is limited, and there is no price assurance or buy-back mechanism.

"The bridge between farmers and industry is broken," he said. "Without it, neither industrial use nor price stability will be achieved."

M Masrur Reaz, chairman of local think tank Policy Exchange Bangladesh, said processed potatoes generate far higher value than fresh ones. Globally, fresh potatoes account for about half of export volume but only 20 percent of value. Processed potatoes make up a third of the volume yet generate more than half of the trade value.

In Bangladesh, processing is limited to 3 percent to 4 percent of output, while exports stand at just 62,000 tonnes, said the economist. "Without value addition, price crashes during bumper harvests will keep hurting farmers."

Agriculture contributes about 12 percent to the gross domestic product of Bangladesh. The processed food sector accounts for only 1.7 percent.

Mohammad Khurshid Alam, chief scientific officer at the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (Bari), said the short winter season limits dry matter accumulation in potatoes. Excessive use of urea further delays maturity and raises moisture content. He said contract farming and area-based zoning are important, with specific regions designated for processing and export varieties.

Other solutions, the scientist said, include developing high dry-matter varieties through public-private partnerships, expanding good agricultural practice certification, improving post-harvest management and rebuilding links between farmers and industry.

Punishing retail prices during low output and throwaway rates during bumper harvests have become a familiar cycle for potato farmers. The swings are recurring and costly, leaving as many as half a crore growers exposed to debt in good years and public anger in bad ones.

Yet agri experts and supply chain players say the problem has little to do with farmers, or even with production. Instead, it reflects how potatoes are treated in policy and planning.

Unlike many other countries, Bangladesh largely views the crop as just another vegetable eaten with rice, not as a basic industrial raw material.

That distinction matters. When production overshoots domestic demand, prices collapse. Farmers absorb the losses, while the economy misses out on value addition that could stabilise incomes and absorb surplus output.

Bangladesh is the world's seventh-largest potato producer. Still, it remains far behind global peers in industrial use of the tuber.

In China, about 15 percent of potato output goes into industrial processing. In the Netherlands, Germany, France and the United States, the share ranges from 60 percent to 65 percent. Russia and Ukraine process 20 percent to 30 percent, while neighbouring India, with similar food habits, uses 5 percent to 7 percent.

Bangladesh, by contrast, processes only 3 percent to 4 percent of its total output, according to industry insiders.

The difference is decisive. In countries where potatoes feed factories, surplus strengthens supply chains. In Bangladesh, surplus simply crashes prices.

After rice, potatoes are the second most produced crop in Bangladesh and a pillar of food security. Yet more than a quarter of output is lost after harvest, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization, which points to weak storage, handling and processing capacity.

WRONG VARIETIES, WEAK PLANNING

Kamruzzaman Kamal, marketing director of Pran-RFL Group, the parent of the local agro processing giant Pran, said industrial processing is limited because most locally grown potatoes are table varieties, not processing-grade crops.

"These potatoes have high moisture and sugar content, which makes them unsuitable for products like French fries. They lose colour and become soft after frying," said Kamal.

Globally, potatoes used for fries, chips and flakes require dry matter of around 22.5 percent. But locally grown potatoes usually contain only 16 percent to 19 percent dry matter, according to scientists.

While potatoes are locally used at home to make chips, and in factories to produce crackers, biscuits and chanachur, the backward linkage industry for flakes and starch is still underdeveloped. Only one or two such factories are currently in production.

Kamal said farmers are not encouraged to grow processing varieties because crop planning is mostly individual-driven rather than coordinated. Many existing varieties are disease-prone, poorly adapted to climate stress and quick to spoil.

Inadequate storage, no grading and sorting at farm level, insufficient cold-chain infrastructure and limited warehousing have further constrained both industrial use and exports, added the Pran-RFL marketing director.

Khurshid Ahmad Farhad, general manager for international business and corporate affairs at Bombay Sweets and Company Limited, a popular food processing brand, said the absence of integrated crop planning and unpredictable weather has kept industrial processing from reaching scale.

Factories producing flakes, slices, chips and biscuits need potatoes of specific size and quality. Bangladesh does not produce enough of these at consistent volumes, he said. Even when quality potatoes are available, production costs are often far higher than international benchmarks, making local products uncompetitive.

"In recent times, costs have risen so sharply that a Dubai-based trader told me they could supply potato flakes at a lower price than we can," Farhad said.

Globally, the largest potato-based industrial products include mashed potatoes and French fries. In Bangladesh, suitable varieties have yet to be developed at a commercial scale, leaving much of the segment untapped.

Although government agencies hold relevant crop data, it is neither centrally coordinated nor used for forecasting, Farhad said. As a result, annual output swings widely between about 80 lakh tonnes and nearly 90 lakh tonnes, with no early warning for the industry.

"This uncertainty is the biggest obstacle. Planning depends on assured availability and consistent quality of raw materials," he said.

THE GLUT, THEN THE CRASH

Strong prices in the 2024 season encouraged farmers to expand potato acreage massively this year in the hope of better returns. Instead, excessive output triggered a severe glut and eventual price fall.

According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, potato production reached a record 1.15 crore tonnes last season, far above annual domestic demand of around 90 lakh tonnes.

Cultivated area rose 8 percent year-on-year to 4.92 lakh hectares in fiscal year 2024-25, while output increased 9 percent from 1.06 crore tonnes the previous year.

The oversupply sent field-level prices tumbling to Tk 9 to Tk 11 per kg, well below the estimated average production cost of Tk 14. In northern regions, costs were higher, at around Tk 20 per kg, according to the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE).

For farmers, the result was debt rather than profit. For the economy, it was another missed chance to channel surplus into value-added uses.

'TYPICAL COLD STORAGE ONLY DELAYS LOSSES'

Bangladesh has expanded cold storage capacity to about 35-40 lakh tonnes. Processing capacity, however, is remarkably low.

Md Mohsin Ali, head of supply chain at Quasem Industries Limited, which produces Sun Chips, said processing capacity stands at just 70,000-80,000 tonnes.

The shortage of modern cold storage designed for processing-grade potatoes is one of the sector's biggest constraints, he said. "Therefore, typical cold storage facilities currently delay losses. It does not create value," he said. "Without factories that can absorb surplus, price crashes will continue."

In many countries, he said, potatoes are a staple food and a major industrial input. In Bangladesh, those consumption patterns and industrial linkages have yet to emerge.

According to Ali, weak policy support, lack of dedicated processing policies and limited investment in research and development are major barriers.

DEMAND EXISTS, QUALITY DOES NOT

Apart from the unavailability of commercial-grade potatoes, the shortage of premium-grade crops is visible even in high-end kitchens.

Md Ershad Ali, assistant sous chef at Pan Pacific Sonargaon Dhaka, a five-star hotel, said they serve potatoes to their guests at every meal, with each buffet offering at least one potato dish.

Some international recipes, however, cannot be prepared with local potatoes due to inconsistent size and grading. Overseas, potatoes arrive uniformly graded and ready for consistent cuts and presentation. Local supplies vary widely.

The hotel uses about 500 kg of potatoes each week. That could rise to 800 kg if uniformly graded, high-quality potatoes were available, he said.

A POLICY BLIND SPOT

FH Ansary, managing director of ACI Agribusiness, said potatoes need to be viewed through four lenses: food, industry, environment and health.

"We treat potatoes as just a vegetable. Elsewhere, they are protein sources, pharmaceutical inputs, packaging material and industrial feedstock," he said.

Ansary said farmers focus on table potatoes because the market is guaranteed. Seeds of processing varieties are scarce, quality-based cultivation is limited, and there is no price assurance or buy-back mechanism.

"The bridge between farmers and industry is broken," he said. "Without it, neither industrial use nor price stability will be achieved."

M Masrur Reaz, chairman of local think tank Policy Exchange Bangladesh, said processed potatoes generate far higher value than fresh ones. Globally, fresh potatoes account for about half of export volume but only 20 percent of value. Processed potatoes make up a third of the volume yet generate more than half of the trade value.

In Bangladesh, processing is limited to 3 percent to 4 percent of output, while exports stand at just 62,000 tonnes, said the economist. "Without value addition, price crashes during bumper harvests will keep hurting farmers."

Agriculture contributes about 12 percent to the gross domestic product of Bangladesh. The processed food sector accounts for only 1.7 percent.

Mohammad Khurshid Alam, chief scientific officer at the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (Bari), said the short winter season limits dry matter accumulation in potatoes. Excessive use of urea further delays maturity and raises moisture content. He said contract farming and area-based zoning are important, with specific regions designated for processing and export varieties.

Other solutions, the scientist said, include developing high dry-matter varieties through public-private partnerships, expanding good agricultural practice certification, improving post-harvest management and rebuilding links between farmers and industry.