Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,262

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

BB board clears winding up of nine non-banks

The Bangladesh Bank is moving to wind up nine ailing non-bank financial institutions as its board has approved their liquidation under the newly framed Bank Resolution Ordinance 2025, the country’s first comprehensive framework for resolving failing banks and non-banks.

BB board clears winding up of nine non-banks

Governor says govt verbally approved Tk 5,000cr to pay depositors; Sammilito Islami Bank gets licence.

The Bangladesh Bank is moving to wind up nine ailing non-bank financial institutions as its board has approved their liquidation under the newly framed Bank Resolution Ordinance 2025, the country's first comprehensive framework for resolving failing banks and non-banks.

The ordinance sets out how distressed institutions may be merged, restructured or closed, and establishes the hierarchy for repaying creditors once assets are sold.

The BB board, chaired by Governor Ahsan H Mansur, granted the approval yesterday, clearing the way for the regulator to formally shut the institutions, appoint liquidators, sell their assets and distribute the proceeds to claimants, a senior central bank official confirmed on condition of anonymity.

The move coincides with another major clean-up operation in the financial sector -- the merger of five troubled shariah-based banks. The BB board also licensed the newly merged Sammilito Islami Bank, marking the largest bank consolidation in the country's history. It is to be the largest Islamic bank in the country now.

Officials say the NBFI liquidations, alongside the bank merger, reflect the regulator's shift towards aggressive intervention after years of deterioration across the financial system.

The nine selected NBFIs are FAS Finance, Bangladesh Industrial Finance Company, Premier Leasing, Fareast Finance, GSP Finance, Prime Finance, Aviva Finance, People's Leasing, and International Leasing.

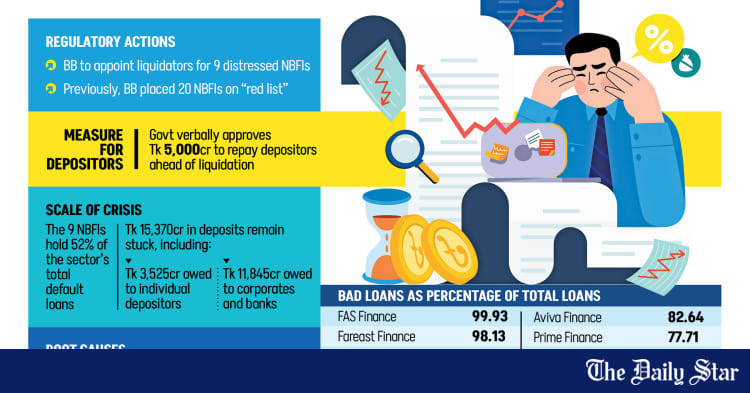

Together, they accounted for 52 percent of total defaulted loans in the NBFI industry, which stood at Tk 25,089 crore at the end of last year, reflecting years of unchecked lending irregularities and erosion of capital.

Seven of the eight NBFIs have an average net asset value of negative Tk 95 per share, leaving little prospect of meeting obligations without state intervention. In other words, when the companies' assets are sold off and debts cleared, there will be nothing, or far too little, left for ordinary shareholders.

DEPOSITORS TO BE PRIORITISED

The BB board's approval comes as the institutions are failing to pay back depositors, many of whom have been waiting months, in some cases years, despite their schemes maturing.

Earlier on Saturday, responding to a query from The Daily Star, Governor Mansur said BB would appoint liquidators "soon".

He also confirmed that depositors would be paid before liquidation proceeds, saying, "The government has already verbally approved around Tk 5,000 crore to repay depositors of these NBFIs."

Mansur said they are moving forward with the liquidation of the companies only to protect depositors. "Returning the deposits of the NBFI customers is our top priority," he said.

For depositors, the collapse of these NBFIs has been devastating. Irregularities in lending, including loans to related parties, poor recovery practices and unchecked concentration of credit, left the institutions unable to meet obligations. As a result, customers' savings remain blocked despite matured schemes.

Khalil Ahmed Khan, a 64-year-old depositor of Aviva Finance, is among those affected. His Tk 23 lakh deposit matured in January, but he has so far received only Tk 8.98 lakh. He met with the top officials at the NBFI but all his attempts have turned futile.

A patient with high blood pressure and diabetes, he said the long delay has made it difficult to pay for treatment. "I need the money urgently to pay my dues and bear the cost of treatment."

BB data shows Tk 15,370 crore in deposits, belonging to both individuals and institutions, remain locked in the nine NBFIs. Of this, Tk 3,525 crore belongs to individuals and Tk 11,845 crore to banks and corporate depositors.

People's Leasing holds the largest volume of unreleased individual deposits at Tk 1,405 crore, followed by Aviva Finance with Tk 809 crore, International Leasing Tk 645 crore, Prime Finance Tk 328 crore and FAS Finance Tk 105 crore.

Industry insiders say the problems in the NBFI sector have deep roots. Unlike banks, non-banks were not subject to equally rigorous supervision, allowing scams and governance failures to accumulate over the years.

Several institutions continued reporting inflated assets and understated losses, masking their worsening condition until the impact became impossible to contain.

Earlier this year, the central bank's Financial Institutions Department shortlisted the nine NBFIs for closure and sent the names to the Bank Resolution Department. The decision followed an assessment 10 months ago, when BB identified 20 NBFIs with critically weak financial health, including high defaulted loans and depleted capital, and placed them in the "red" category.

The remaining 11 NBFIs are: CVC Finance, Bay Leasing, Islamic Finance, Meridian Finance, Hajj Finance, National Finance, IIDFC, Uttara Finance, Phoenix Finance, First Finance and Union Capital.

The BB has asked them to present viable recovery strategies.

Governor says govt verbally approved Tk 5,000cr to pay depositors; Sammilito Islami Bank gets licence.

The Bangladesh Bank is moving to wind up nine ailing non-bank financial institutions as its board has approved their liquidation under the newly framed Bank Resolution Ordinance 2025, the country's first comprehensive framework for resolving failing banks and non-banks.

The ordinance sets out how distressed institutions may be merged, restructured or closed, and establishes the hierarchy for repaying creditors once assets are sold.

The BB board, chaired by Governor Ahsan H Mansur, granted the approval yesterday, clearing the way for the regulator to formally shut the institutions, appoint liquidators, sell their assets and distribute the proceeds to claimants, a senior central bank official confirmed on condition of anonymity.

The move coincides with another major clean-up operation in the financial sector -- the merger of five troubled shariah-based banks. The BB board also licensed the newly merged Sammilito Islami Bank, marking the largest bank consolidation in the country's history. It is to be the largest Islamic bank in the country now.

Officials say the NBFI liquidations, alongside the bank merger, reflect the regulator's shift towards aggressive intervention after years of deterioration across the financial system.

The nine selected NBFIs are FAS Finance, Bangladesh Industrial Finance Company, Premier Leasing, Fareast Finance, GSP Finance, Prime Finance, Aviva Finance, People's Leasing, and International Leasing.

Together, they accounted for 52 percent of total defaulted loans in the NBFI industry, which stood at Tk 25,089 crore at the end of last year, reflecting years of unchecked lending irregularities and erosion of capital.

Seven of the eight NBFIs have an average net asset value of negative Tk 95 per share, leaving little prospect of meeting obligations without state intervention. In other words, when the companies' assets are sold off and debts cleared, there will be nothing, or far too little, left for ordinary shareholders.

DEPOSITORS TO BE PRIORITISED

The BB board's approval comes as the institutions are failing to pay back depositors, many of whom have been waiting months, in some cases years, despite their schemes maturing.

Earlier on Saturday, responding to a query from The Daily Star, Governor Mansur said BB would appoint liquidators "soon".

He also confirmed that depositors would be paid before liquidation proceeds, saying, "The government has already verbally approved around Tk 5,000 crore to repay depositors of these NBFIs."

Mansur said they are moving forward with the liquidation of the companies only to protect depositors. "Returning the deposits of the NBFI customers is our top priority," he said.

For depositors, the collapse of these NBFIs has been devastating. Irregularities in lending, including loans to related parties, poor recovery practices and unchecked concentration of credit, left the institutions unable to meet obligations. As a result, customers' savings remain blocked despite matured schemes.

Khalil Ahmed Khan, a 64-year-old depositor of Aviva Finance, is among those affected. His Tk 23 lakh deposit matured in January, but he has so far received only Tk 8.98 lakh. He met with the top officials at the NBFI but all his attempts have turned futile.

A patient with high blood pressure and diabetes, he said the long delay has made it difficult to pay for treatment. "I need the money urgently to pay my dues and bear the cost of treatment."

BB data shows Tk 15,370 crore in deposits, belonging to both individuals and institutions, remain locked in the nine NBFIs. Of this, Tk 3,525 crore belongs to individuals and Tk 11,845 crore to banks and corporate depositors.

People's Leasing holds the largest volume of unreleased individual deposits at Tk 1,405 crore, followed by Aviva Finance with Tk 809 crore, International Leasing Tk 645 crore, Prime Finance Tk 328 crore and FAS Finance Tk 105 crore.

Industry insiders say the problems in the NBFI sector have deep roots. Unlike banks, non-banks were not subject to equally rigorous supervision, allowing scams and governance failures to accumulate over the years.

Several institutions continued reporting inflated assets and understated losses, masking their worsening condition until the impact became impossible to contain.

Earlier this year, the central bank's Financial Institutions Department shortlisted the nine NBFIs for closure and sent the names to the Bank Resolution Department. The decision followed an assessment 10 months ago, when BB identified 20 NBFIs with critically weak financial health, including high defaulted loans and depleted capital, and placed them in the "red" category.

The remaining 11 NBFIs are: CVC Finance, Bay Leasing, Islamic Finance, Meridian Finance, Hajj Finance, National Finance, IIDFC, Uttara Finance, Phoenix Finance, First Finance and Union Capital.

The BB has asked them to present viable recovery strategies.