Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 17,262

- Likes

- 8,334

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Banking must be free from political influence: experts

The banking sector must remain free from political interference and be managed professionally with government support to restore confidence and stability, financial experts said on Thursday.

www.newagebd.net

www.newagebd.net

Banking must be free from political influence: experts

Staff Correspondent 18 December, 2025, 23:31

BB governor Ahsan H Mansur, CPD executive director Fahmida Khatun and MTB managing director Syed Mahbubur Rahman, among others, are present at a discussion titled ‘Banking Sector Reforms: Challenges and Way Forward’ in the capital on Thursday. | Press release photo

The banking sector must remain free from political interference and be managed professionally with government support to restore confidence and stability, financial experts said on Thursday.

They made the remarks at a discussion titled ‘Banking Sector Reforms: Challenges and Way Forward’, organised by the Economic Reporters’ Forum in Dhaka, against the backdrop of mounting loan defaults and deepening governance failures in the financial system.

Speakers stressed that political parties must clearly state their plans for banking sector reform in their election manifestos and remain accountable for those commitments.

While government oversight is necessary to safeguard public interest, they said, politically motivated intervention in bank management has repeatedly undermined discipline and risk management.

Bangladesh Bank governor Ahsan H Mansur called for a firm political consensus to keep banks free from interference.

He said protecting the banking sector from political motives was a moral responsibility of all political parties. Some parties, he noted, have already pledged to strengthen banks and ensure the independence of the central bank, and the country now expects those promises to be implemented in practice.

Mansur emphasised that the financial sector is the backbone of the economy and warned that economic progress would remain fragile unless banking reform receives priority both in election manifestos and post-election policymaking.

He strongly pushed for full autonomy of Bangladesh Bank, arguing that international-standard legislation is needed to shield the governor from political pressure. Removal from office, he said, should only be possible through court rulings based on proven misconduct or corruption.

Centre for Policy Dialogue executive director Fahmida Khatun echoed the governor’s concerns, describing the upcoming national election as a critical turning point.

She said political parties must clearly spell out how they intend to discipline and reform the banking sector.

Past political interference, weak policy enforcement and unchecked lending had pushed the sector to the brink, she said.

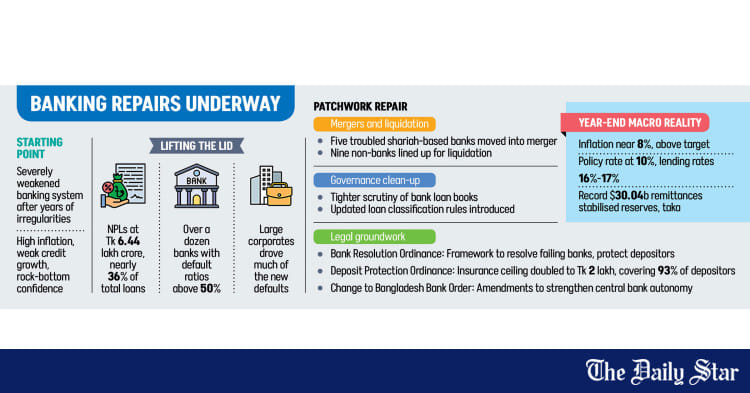

According to Fahmida, defaulted loans have now climbed to Tk 6.44 lakh crore, close to the proposed Tk 7.9 lakh crore national budget for 2025–26.

Mutual Trust Bank managing director Syed Mahbubur Rahman said that the crisis intensified after the takeover of Islami Bank in 2017, which opened the door to widespread malpractice.

While recent political changes have brought some improvement, he cautioned that lasting reform will depend on sustained political will rather than technical banking measures alone, he said.

As part of the reform drive, governor Mansur said that all loans exceeding Tk 20 crore would undergo fresh scrutiny.

The reassessment aims to uncover past irregularities and restore discipline in a sector burdened by weak governance and soaring defaults.

He warned that bank officials and directors would be held accountable if such loans lack proper collateral, adding that the central bank would not conceal facts even if the true picture appears alarming.

Defaulted loans, he said, have reached nearly 36 per cent of total disbursements.

Mansur said that the legal process to merge five banks has already been completed.

Within days, the newly formed Sammilito Islami Bank will change logos, signboards and branch names, and overlapping branches will be consolidated or relocated to underserved areas, he added.

Alongside the merger, nine financial institutions will be liquidated.

He assured that general depositors would receive their full funds, while institutional depositors would get partial repayments, and that all deposits of the merged banks would remain safe.

On reserves, the governor said Bangladesh would rebuild foreign

exchange buffers through its own capacity rather than external borrowing, targeting $34–35 billion by the end of the fiscal year through market-based dollar purchases.

Explaining the cancellation of incentive bonuses for bank employees, he said responsibility for failures extends beyond top management, as lending decisions are largely made at branch level, and officials who ignore risks or irregularities will also face consequences.

Staff Correspondent 18 December, 2025, 23:31

BB governor Ahsan H Mansur, CPD executive director Fahmida Khatun and MTB managing director Syed Mahbubur Rahman, among others, are present at a discussion titled ‘Banking Sector Reforms: Challenges and Way Forward’ in the capital on Thursday. | Press release photo

The banking sector must remain free from political interference and be managed professionally with government support to restore confidence and stability, financial experts said on Thursday.

They made the remarks at a discussion titled ‘Banking Sector Reforms: Challenges and Way Forward’, organised by the Economic Reporters’ Forum in Dhaka, against the backdrop of mounting loan defaults and deepening governance failures in the financial system.

Speakers stressed that political parties must clearly state their plans for banking sector reform in their election manifestos and remain accountable for those commitments.

While government oversight is necessary to safeguard public interest, they said, politically motivated intervention in bank management has repeatedly undermined discipline and risk management.

Bangladesh Bank governor Ahsan H Mansur called for a firm political consensus to keep banks free from interference.

He said protecting the banking sector from political motives was a moral responsibility of all political parties. Some parties, he noted, have already pledged to strengthen banks and ensure the independence of the central bank, and the country now expects those promises to be implemented in practice.

Mansur emphasised that the financial sector is the backbone of the economy and warned that economic progress would remain fragile unless banking reform receives priority both in election manifestos and post-election policymaking.

He strongly pushed for full autonomy of Bangladesh Bank, arguing that international-standard legislation is needed to shield the governor from political pressure. Removal from office, he said, should only be possible through court rulings based on proven misconduct or corruption.

Centre for Policy Dialogue executive director Fahmida Khatun echoed the governor’s concerns, describing the upcoming national election as a critical turning point.

She said political parties must clearly spell out how they intend to discipline and reform the banking sector.

Past political interference, weak policy enforcement and unchecked lending had pushed the sector to the brink, she said.

According to Fahmida, defaulted loans have now climbed to Tk 6.44 lakh crore, close to the proposed Tk 7.9 lakh crore national budget for 2025–26.

Mutual Trust Bank managing director Syed Mahbubur Rahman said that the crisis intensified after the takeover of Islami Bank in 2017, which opened the door to widespread malpractice.

While recent political changes have brought some improvement, he cautioned that lasting reform will depend on sustained political will rather than technical banking measures alone, he said.

As part of the reform drive, governor Mansur said that all loans exceeding Tk 20 crore would undergo fresh scrutiny.

The reassessment aims to uncover past irregularities and restore discipline in a sector burdened by weak governance and soaring defaults.

He warned that bank officials and directors would be held accountable if such loans lack proper collateral, adding that the central bank would not conceal facts even if the true picture appears alarming.

Defaulted loans, he said, have reached nearly 36 per cent of total disbursements.

Mansur said that the legal process to merge five banks has already been completed.

Within days, the newly formed Sammilito Islami Bank will change logos, signboards and branch names, and overlapping branches will be consolidated or relocated to underserved areas, he added.

Alongside the merger, nine financial institutions will be liquidated.

He assured that general depositors would receive their full funds, while institutional depositors would get partial repayments, and that all deposits of the merged banks would remain safe.

On reserves, the governor said Bangladesh would rebuild foreign

exchange buffers through its own capacity rather than external borrowing, targeting $34–35 billion by the end of the fiscal year through market-based dollar purchases.

Explaining the cancellation of incentive bonuses for bank employees, he said responsibility for failures extends beyond top management, as lending decisions are largely made at branch level, and officials who ignore risks or irregularities will also face consequences.