Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,326

- Likes

- 8,086

- Nation

- Axis Group

Steam Power and Scientific Knowledge in Early British Bengal

Photo 2 : Detail from "Chandpaul Ghaut. Steam Engine. Supreme Court," by William Wood, A Series of Twenty-Eight Panoramic Views of Calcutta (1833), Plate 1; from the British Library Archive shelfmark 1781.c.22

In Europe, steam power evolved gradually and uncertainly over the course of the eighteenth century, with innovative peaks and long plateaus, from Thomas Savery's steam pump (1698) via Thomas Newcomen's reciprocating atmospheric engine (1712) to James Watt and Matthew Boulton's double-acting rotative steam engine with a separate condenser (1765-90). The first steamer to complete the journey from England to India, the Enterprize (an "auxiliary" paddle ship equipped with sails), left Falmouth on August 16, 1825 and arrived in Calcutta via the Cape of Good Hope a disappointing 113 days later, of which (due to bad weather and exhausted fuel) only 62 were under steam. Between 1822 and 1837, the number of steam engines working in Bengal rose from 2 to 67, and by 1845, according to the Bengal Hurkaru newspaper, there were 150 engines in use (mostly imported). By the end of this period, in 1844, the journalist J.H. Stocqueler could report that "On approaching Calcutta, the smoking chimneys of steam-engines are now seen in every direction, on either side of the river, presenting the gratifying appearance of a seat of numerous extensive manufactories, vying with many British cities."

During the early year of the 19th century, Bengal was becoming the epicenter of an imperial imagination in which steam in particular was firmly fixed as an engine that would diffuse European civilization. The public history of steam power in India begins with three remarkable scenes from the 1820s.

Golak's engine was displayed at the Society's annual exhibition on January 16 at Calcutta's Town Hall. In its report, the Society further emphasized that Golak designed and built the engine "without any assistance whatever from European artists upon the mode, of a large Steam Engine belonging to the missionaries at Serampore," for which the "ingenious blacksmith" was awarded a prize of 50 rupees.

First, just north of Calcutta in the Danish colony of Serampore (Srirampur), on March 27, 1820 the English Baptist missionaries staged a demonstration of their new engine imported from Messrs. Thwaites and Rothwell of Bolton to assist with paper production for the mission press: "The 'machine of fire,' as they called it, brought crowds of natives to the mission, whose curiosity tried the patience of the engineman imported to work it; while many a European who had never seen machinery driven by steam came to study and to copy it."

Photo 1: The Asiatic Journal in London

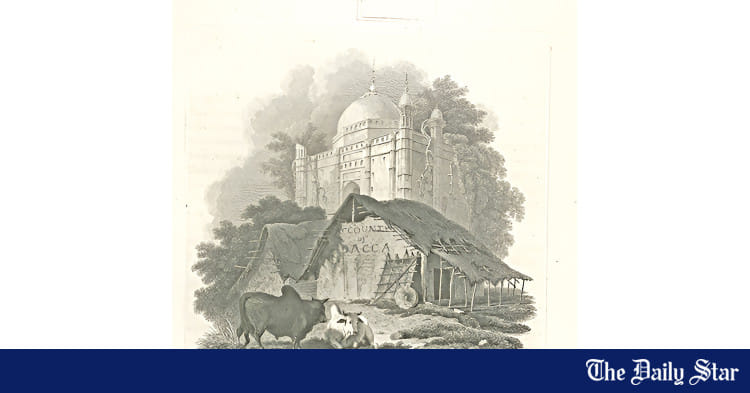

The second high-profile stationary engine in Bengal went into operation two and a half years later, on November 1, 1822, in Calcutta at Chandpal Ghat to supply water from the Hugli river via aqueducts to the streets of the city's "White Town" in order to keep down the dust.

In the following summer, "At exactly nine minutes past four on Saturday afternoon (12th July) the first steam vessel, which ever floated on the waters of the East," the Diana Packet, "left the stocks at Kyd's Yard, Kidderpore," with a more public launch following on the morning of August 9, when the Diana departed from Chandpal Ghat, "stemming the rapid freshes of the river with a velocity perfectly astonishing." Bearing a party including Colonel Jacob Krefting, Governor of Serampore, and his suite, the Diana steamed to Chinsurah against a strong tide, making the journey in six to seven hours and then returning by way of Serampore, where an "elegant entertainment" had been "prepared for the occasion," arriving back in Calcutta on the next morning.

Here is the account reproduced by The Asiatic Journal in London from The Calcutta Journal in Bengal: (See Photo 1)

All the terms of the Romantic sublime are there, so we expect the minds of the beholders to be awed and elevated, yet their wonder is "stupid," their fears "superstitious," their amazement or astonishment, whether "silent" or "loud," indifferently a sign of utter incomprehension. For Edmund Burke in his famous Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) and, especially, for Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Judgment (1790), what we call sublime does not reside in the object so described but rather in the mind that apprehends it. Kant is explicit that "the judgement upon the Sublime in nature needs culture (more than the judgement upon the Beautiful)": "That the mind be attuned to feel the sublime postulates a susceptibility of the mind for ideas … In fact, without the development of moral ideas, that which we, prepared by culture, call sublime presents itself to the uneducated man merely as terrible." Unprepared by culture, the crowds of natives who gather to see the Baptist missionaries' "machine of fire" in 1820 experienced only an irritating curiosity, while now in 1823 "the more ignorant natives" experience only terror.

Having already noted that "Almost all the heathen temples were dark," Burke, in fact, denominated darkness and blackness themselves as intrinsically terrible objective properties, citing the example of a boy who "saw a black object," which "gave him great uneasiness," and then "some time after, upon accidentally seeing a negro woman, … was struck with great horror at the sight." In accounts of steam as sublime, accordingly, it is the European viewer whose mind is elevated and "admitted … into the Counsels of the Almighty by a consideration of his works." Thus elevated, the European mind is prepared, as The Calcutta Journal concludes its depiction of the Diana Packet, to "promote the cause of science and the arts, and add to the sum of human enjoyments." The native, on the contrary, like a dark, heathen temple, can be an object, not a subject, of the sublime.

During the early years of the 19th century, Bengal was becoming the epicenter of an imperial imagination in which steam in particular was firmly fixed as an engine that would diffuse European civilization.

The crowds that came to witness the Diana dispelling the darkness recall the contrast established in the account of the Serampore engine between collective and childlike native curiosity, which "tried the patience of the engineman," and the individualized and mature curiosity of "many a European who … came to study and to copy it." One Indian not only came to study and copy it, however, but then proceeded to build a working engine based on its design. We do not know if Golak Chandra, blacksmith of Titagarh, immediately opposite Serampore, crossed the river on March 27, 1820 to join the "crowds of natives" curious about the new machine. But he did cross the river to study it many times thereafter: at its meeting on January 9, 1828, the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India resolved, "at the suggestion of the Rev. Dr. Carey, that permission be given to Goluk-chundra, a blacksmith of Titigur, to exhibit on Wednesday next, a Steam Engine made by himself without the aid of any European artist." Golak's engine was then displayed at the Society's annual exhibition on January 16 at Calcutta's Town Hall. In its report, the Society further emphasized that Golak designed and built the engine "without any assistance whatever from European artists upon the mode, of a large Steam Engine belonging to the missionaries at Serampore," for which the "ingenious blacksmith" was awarded a prize of 50 rupees. A contemporaneous account in the Calcutta Gazette echoed the phrase "without any assistance whatever from European artists" while adding its own praise for the "native ingenuity" and "imitative skill" of the "ingenious Blacksmith."

Photo 4 : Photograph of the model of steam engine preserved at Serampore

The story of Golak Chandra's engine, for scientist and scholar Professor Amitabha Ghosh, demolishes a myth, making the "plotting of Indian dependence as a function of technological incapability even in the era of steam a spurious fabrication." But something else is at stake too in the early nineteenth century. If we zoom out to the context in which this engine was exhibited in 1828, at an exhibition of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society, we find, according to the Society's Prospectus, written by the Baptist missionary William Carey on April 15, 1820, a mere three weeks after the demonstration of the Mission's new steam engine, that "It is peculiarly desirable that Native gentlemen should be eligible as members of the Society, because one of its chief objects will be the improvement of their estates, and of the peasantry which reside thereon. They should therefore not only be eligible as members, but also as officers of the Society in precisely the same manner as Europeans." A further reason why it was peculiarly desirable to associate "Native Gentlemen of landed estates with Europeans who have studied this subject" was that "we should gradually impart to them more correct ideas of the value of landed property, of the possibility of improving it, and of the best methods of accomplishing so desirable an end." Such "improvements" would bring about "the gradual conquest of the indolence which in Asiatics is almost become a second nature, – and the introduction of habits of cleanliness … in the place of squalid wretchedness, neglect, and confusion." Through the diffusion of western science to the native members of the Society, "industry and virtue" would replace "idleness and vice."

In this light, the insistence that Golak's ingenuity was a form of "imitative skill" and the emphasis here on the "improvement" of native estates (Britons being forbidden from owning land) reveal a tension in the period between what historian Kapil Raj has called the later historiographical perspectives of "diffusionism" and "relocationism" with respect to the creation and transmission of scientific knowledge. According to the dominant diffusionist model, science is developed in the West and then spread to the East as "the embodiment of basic values of truth and rationality, the motor of moral, social, and material progress, the marker of civilization itself." Knowledge and technologies are fundamentally stable in function and significance, adapting the new location to the universal values and progress they bear while remaining themselves unmodified by local environment or experience. The alternative "relocationist" perspective proposed by Raj, on the contrary, rooted in the New Imperial History's emphasis on asymmetric circulation and the mutual constitution of Britain and its empire, suggests that "South Asia was not a space for the simple application of European knowledge" but rather "was an active, although unequal, participant in an emerging world order of knowledge … [T]he contact zone was a site for the production of certified knowledges which would not have come into being but for the intercultural encounter between South Asian and European intellectual and material practices."

On the one hand, then, Golak is a "mimic" engineer, copying a European imported prototype and demonstrating the native capacity, in the well-known language of Macaulay's "Minute on Indian Education" (1835), to become "English … in intellect." And the same goes for the 500 native members of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society over the remainder of the nineteenth century, who, for Macaulay, would join the "interpreter" class – "a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect" – prepared "to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population."

Photo 3 : The Enterprize departed Falmouth on August 16, 1825, bound for India. Despite high hopes, its journey to Calcutta via the Cape of Good Hope took a disappointing 113 days, marking the first steamship voyage from England to India.

On the other hand, the activities and language of the Society work against its diffusionist ideology: the "first endeavours" of the Society "would be directed to the obtaining of information upon the almost innumerable subjects which present themselves," and "Native Gentlemen" would thus be essential not just to the civilizing process by which they would receive communicated European science but to the Society's own acquisition of a hybridized "stock of knowledge": "the methods employed to raise crops, and conduct the other parts of rural economy must so vary with soil, climate, and other local circumstances, as to make it impossible for any individual to be practically acquainted with them all. Too much praise can scarcely be given to local establishments whether public or private." Carey, Professor of Bengali, Sanskrit, and Marathi at the College of Fort William and as devout a practical botanist as a Particular Baptist, was far less invested in assimilation and anglicization than the evangelical wing of the Church of England associated with Charles Grant, Zachary Macaulay, and the Clapham Sect, or than Alexander Duff of the Scottish Church Mission: above all, for Carey local circumstances (and languages) were always paramount. And finally, in a moment of reverse-diffusionism, the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, founded in 1820 and shaped by intercultural encounter, translation, and local practices, then formed the model for the Royal Agricultural Society of England, founded in 1838.

As the convergence of steam power, science, and colonialism in early British Bengal shows, the relocation of technology undermined the equation between stable knowledge and the transfer of civilization from West to East. From the effect of the Diana's "triumph of science over the elements, on some of the more ignorant natives" to the display of Golak's engine before the annual exhibition of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, the production of knowledge in the contact zone was always a form of hybridization bearing the marks of specific and unequal relationships of power.

Daniel E. White is Professor of English at the University of Toronto, Canada. His new book, Romanticism, Liberal Imperialism, and Technology in Early British India: "The all-changing power of steam," is forthcoming from Palgrave.

Photo 2 : Detail from "Chandpaul Ghaut. Steam Engine. Supreme Court," by William Wood, A Series of Twenty-Eight Panoramic Views of Calcutta (1833), Plate 1; from the British Library Archive shelfmark 1781.c.22

In Europe, steam power evolved gradually and uncertainly over the course of the eighteenth century, with innovative peaks and long plateaus, from Thomas Savery's steam pump (1698) via Thomas Newcomen's reciprocating atmospheric engine (1712) to James Watt and Matthew Boulton's double-acting rotative steam engine with a separate condenser (1765-90). The first steamer to complete the journey from England to India, the Enterprize (an "auxiliary" paddle ship equipped with sails), left Falmouth on August 16, 1825 and arrived in Calcutta via the Cape of Good Hope a disappointing 113 days later, of which (due to bad weather and exhausted fuel) only 62 were under steam. Between 1822 and 1837, the number of steam engines working in Bengal rose from 2 to 67, and by 1845, according to the Bengal Hurkaru newspaper, there were 150 engines in use (mostly imported). By the end of this period, in 1844, the journalist J.H. Stocqueler could report that "On approaching Calcutta, the smoking chimneys of steam-engines are now seen in every direction, on either side of the river, presenting the gratifying appearance of a seat of numerous extensive manufactories, vying with many British cities."

During the early year of the 19th century, Bengal was becoming the epicenter of an imperial imagination in which steam in particular was firmly fixed as an engine that would diffuse European civilization. The public history of steam power in India begins with three remarkable scenes from the 1820s.

Golak's engine was displayed at the Society's annual exhibition on January 16 at Calcutta's Town Hall. In its report, the Society further emphasized that Golak designed and built the engine "without any assistance whatever from European artists upon the mode, of a large Steam Engine belonging to the missionaries at Serampore," for which the "ingenious blacksmith" was awarded a prize of 50 rupees.

First, just north of Calcutta in the Danish colony of Serampore (Srirampur), on March 27, 1820 the English Baptist missionaries staged a demonstration of their new engine imported from Messrs. Thwaites and Rothwell of Bolton to assist with paper production for the mission press: "The 'machine of fire,' as they called it, brought crowds of natives to the mission, whose curiosity tried the patience of the engineman imported to work it; while many a European who had never seen machinery driven by steam came to study and to copy it."

Photo 1: The Asiatic Journal in London

The second high-profile stationary engine in Bengal went into operation two and a half years later, on November 1, 1822, in Calcutta at Chandpal Ghat to supply water from the Hugli river via aqueducts to the streets of the city's "White Town" in order to keep down the dust.

In the following summer, "At exactly nine minutes past four on Saturday afternoon (12th July) the first steam vessel, which ever floated on the waters of the East," the Diana Packet, "left the stocks at Kyd's Yard, Kidderpore," with a more public launch following on the morning of August 9, when the Diana departed from Chandpal Ghat, "stemming the rapid freshes of the river with a velocity perfectly astonishing." Bearing a party including Colonel Jacob Krefting, Governor of Serampore, and his suite, the Diana steamed to Chinsurah against a strong tide, making the journey in six to seven hours and then returning by way of Serampore, where an "elegant entertainment" had been "prepared for the occasion," arriving back in Calcutta on the next morning.

Here is the account reproduced by The Asiatic Journal in London from The Calcutta Journal in Bengal: (See Photo 1)

All the terms of the Romantic sublime are there, so we expect the minds of the beholders to be awed and elevated, yet their wonder is "stupid," their fears "superstitious," their amazement or astonishment, whether "silent" or "loud," indifferently a sign of utter incomprehension. For Edmund Burke in his famous Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) and, especially, for Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Judgment (1790), what we call sublime does not reside in the object so described but rather in the mind that apprehends it. Kant is explicit that "the judgement upon the Sublime in nature needs culture (more than the judgement upon the Beautiful)": "That the mind be attuned to feel the sublime postulates a susceptibility of the mind for ideas … In fact, without the development of moral ideas, that which we, prepared by culture, call sublime presents itself to the uneducated man merely as terrible." Unprepared by culture, the crowds of natives who gather to see the Baptist missionaries' "machine of fire" in 1820 experienced only an irritating curiosity, while now in 1823 "the more ignorant natives" experience only terror.

Having already noted that "Almost all the heathen temples were dark," Burke, in fact, denominated darkness and blackness themselves as intrinsically terrible objective properties, citing the example of a boy who "saw a black object," which "gave him great uneasiness," and then "some time after, upon accidentally seeing a negro woman, … was struck with great horror at the sight." In accounts of steam as sublime, accordingly, it is the European viewer whose mind is elevated and "admitted … into the Counsels of the Almighty by a consideration of his works." Thus elevated, the European mind is prepared, as The Calcutta Journal concludes its depiction of the Diana Packet, to "promote the cause of science and the arts, and add to the sum of human enjoyments." The native, on the contrary, like a dark, heathen temple, can be an object, not a subject, of the sublime.

During the early years of the 19th century, Bengal was becoming the epicenter of an imperial imagination in which steam in particular was firmly fixed as an engine that would diffuse European civilization.

The crowds that came to witness the Diana dispelling the darkness recall the contrast established in the account of the Serampore engine between collective and childlike native curiosity, which "tried the patience of the engineman," and the individualized and mature curiosity of "many a European who … came to study and to copy it." One Indian not only came to study and copy it, however, but then proceeded to build a working engine based on its design. We do not know if Golak Chandra, blacksmith of Titagarh, immediately opposite Serampore, crossed the river on March 27, 1820 to join the "crowds of natives" curious about the new machine. But he did cross the river to study it many times thereafter: at its meeting on January 9, 1828, the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India resolved, "at the suggestion of the Rev. Dr. Carey, that permission be given to Goluk-chundra, a blacksmith of Titigur, to exhibit on Wednesday next, a Steam Engine made by himself without the aid of any European artist." Golak's engine was then displayed at the Society's annual exhibition on January 16 at Calcutta's Town Hall. In its report, the Society further emphasized that Golak designed and built the engine "without any assistance whatever from European artists upon the mode, of a large Steam Engine belonging to the missionaries at Serampore," for which the "ingenious blacksmith" was awarded a prize of 50 rupees. A contemporaneous account in the Calcutta Gazette echoed the phrase "without any assistance whatever from European artists" while adding its own praise for the "native ingenuity" and "imitative skill" of the "ingenious Blacksmith."

Photo 4 : Photograph of the model of steam engine preserved at Serampore

The story of Golak Chandra's engine, for scientist and scholar Professor Amitabha Ghosh, demolishes a myth, making the "plotting of Indian dependence as a function of technological incapability even in the era of steam a spurious fabrication." But something else is at stake too in the early nineteenth century. If we zoom out to the context in which this engine was exhibited in 1828, at an exhibition of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society, we find, according to the Society's Prospectus, written by the Baptist missionary William Carey on April 15, 1820, a mere three weeks after the demonstration of the Mission's new steam engine, that "It is peculiarly desirable that Native gentlemen should be eligible as members of the Society, because one of its chief objects will be the improvement of their estates, and of the peasantry which reside thereon. They should therefore not only be eligible as members, but also as officers of the Society in precisely the same manner as Europeans." A further reason why it was peculiarly desirable to associate "Native Gentlemen of landed estates with Europeans who have studied this subject" was that "we should gradually impart to them more correct ideas of the value of landed property, of the possibility of improving it, and of the best methods of accomplishing so desirable an end." Such "improvements" would bring about "the gradual conquest of the indolence which in Asiatics is almost become a second nature, – and the introduction of habits of cleanliness … in the place of squalid wretchedness, neglect, and confusion." Through the diffusion of western science to the native members of the Society, "industry and virtue" would replace "idleness and vice."

In this light, the insistence that Golak's ingenuity was a form of "imitative skill" and the emphasis here on the "improvement" of native estates (Britons being forbidden from owning land) reveal a tension in the period between what historian Kapil Raj has called the later historiographical perspectives of "diffusionism" and "relocationism" with respect to the creation and transmission of scientific knowledge. According to the dominant diffusionist model, science is developed in the West and then spread to the East as "the embodiment of basic values of truth and rationality, the motor of moral, social, and material progress, the marker of civilization itself." Knowledge and technologies are fundamentally stable in function and significance, adapting the new location to the universal values and progress they bear while remaining themselves unmodified by local environment or experience. The alternative "relocationist" perspective proposed by Raj, on the contrary, rooted in the New Imperial History's emphasis on asymmetric circulation and the mutual constitution of Britain and its empire, suggests that "South Asia was not a space for the simple application of European knowledge" but rather "was an active, although unequal, participant in an emerging world order of knowledge … [T]he contact zone was a site for the production of certified knowledges which would not have come into being but for the intercultural encounter between South Asian and European intellectual and material practices."

On the one hand, then, Golak is a "mimic" engineer, copying a European imported prototype and demonstrating the native capacity, in the well-known language of Macaulay's "Minute on Indian Education" (1835), to become "English … in intellect." And the same goes for the 500 native members of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society over the remainder of the nineteenth century, who, for Macaulay, would join the "interpreter" class – "a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect" – prepared "to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population."

Photo 3 : The Enterprize departed Falmouth on August 16, 1825, bound for India. Despite high hopes, its journey to Calcutta via the Cape of Good Hope took a disappointing 113 days, marking the first steamship voyage from England to India.

On the other hand, the activities and language of the Society work against its diffusionist ideology: the "first endeavours" of the Society "would be directed to the obtaining of information upon the almost innumerable subjects which present themselves," and "Native Gentlemen" would thus be essential not just to the civilizing process by which they would receive communicated European science but to the Society's own acquisition of a hybridized "stock of knowledge": "the methods employed to raise crops, and conduct the other parts of rural economy must so vary with soil, climate, and other local circumstances, as to make it impossible for any individual to be practically acquainted with them all. Too much praise can scarcely be given to local establishments whether public or private." Carey, Professor of Bengali, Sanskrit, and Marathi at the College of Fort William and as devout a practical botanist as a Particular Baptist, was far less invested in assimilation and anglicization than the evangelical wing of the Church of England associated with Charles Grant, Zachary Macaulay, and the Clapham Sect, or than Alexander Duff of the Scottish Church Mission: above all, for Carey local circumstances (and languages) were always paramount. And finally, in a moment of reverse-diffusionism, the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, founded in 1820 and shaped by intercultural encounter, translation, and local practices, then formed the model for the Royal Agricultural Society of England, founded in 1838.

As the convergence of steam power, science, and colonialism in early British Bengal shows, the relocation of technology undermined the equation between stable knowledge and the transfer of civilization from West to East. From the effect of the Diana's "triumph of science over the elements, on some of the more ignorant natives" to the display of Golak's engine before the annual exhibition of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India, the production of knowledge in the contact zone was always a form of hybridization bearing the marks of specific and unequal relationships of power.

Daniel E. White is Professor of English at the University of Toronto, Canada. His new book, Romanticism, Liberal Imperialism, and Technology in Early British India: "The all-changing power of steam," is forthcoming from Palgrave.