Saif

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2024

- Messages

- 16,529

- Likes

- 8,140

- Nation

- Residence

- Axis Group

Restoring investor confidence biggest challenge ahead

As a new year dawns, an economic post-mortem of the bygone year reflects a story of resilience, reform and recalibration. While public expectations were sky-high at the outset of the interim government, the economy failed to stage a decisive turnaround over the past one and a half years. Neverthele

Restoring investor confidence biggest challenge ahead

Atiqul Kabir Tuhin

Published :

Dec 31, 2025 23:17

Updated :

Dec 31, 2025 23:17

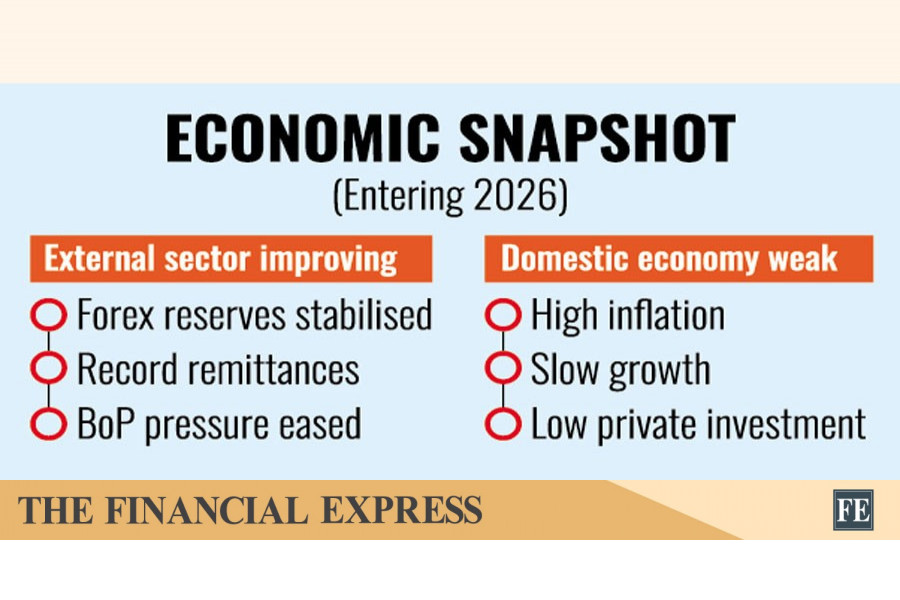

As a new year dawns, an economic post-mortem of the bygone year reflects a story of resilience, reform and recalibration. While public expectations were sky-high at the outset of the interim government, the economy failed to stage a decisive turnaround over the past one and a half years. Nevertheless, a degree of macroeconomic stability has been achieved. Fiscal discipline has been partially restored, along with tighter oversight of the financial sector. The exchange rate has stabilised, and the dollar crisis has largely been brought under control. Inflation has begun to ease, although it remains stubbornly high and continues to erode purchasing power.

However, the most critical driver of economic recovery - investor confidence - has not been restored. The prolonged crisis of trust continues to dampen investment and business sentiment. Political unrest and uncertainty have not subsided. Rather, volatility has intensified. Recent incidents of vandalism targeting private institutions by radical elements, carried out through 'mob justice', have further undermined stability. Therefore, in 2026, maintaining political stability, restoring investor confidence and carrying forward the reform initiatives will be some of the formidable challenges on the economic front.

On the external front, the picture is comparatively brighter. A range of policy measures over the past 18 months has brought considerable relief to the balance of payments. Capital flight appears to have declined significantly. Meanwhile, a sharp rise in remittance inflows, coupled with a modest increase in export earnings, has boosted the supply of dollars in the market. As a result, local currency taka gained strength against dollar. However, authorities have refrained from lowering the dollar price too aggressively to sustain remittance and export growth. Improved dollar liquidity has also reduced the appetite for high-interest foreign borrowing. All recent government loans from external sources have been on concessional terms.

During Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian regime, there were widespread allegations that remittances and export proceeds were diverted through hundi. Moreover, large sums of money were siphoned off under the guise of imports. As a result, the country's foreign exchange reserves were in a free fall. Net foreign exchange reserves had declined to $17 billion. The exchange rate peaked at Tk 132 per dollar. Amid a prolonged dollar crisis, the government had even imposed import restrictions and deferred payments on large-scale foreign loans.

Since then, the free fall in foreign exchange reserves has been halted. The exchange rate has stabilised at around Tk 122 per dollar, and reserves have rebounded to nearly $28 billion. This recovery has been driven mainly by the curbing of looting and money laundering, alongside strong remittance inflows and export growth. Remittances grew by nearly 27 per cent in the last fiscal year and by more than 17 per cent in the current fiscal year up to November. Export earnings increased by 8 per cent in FY2025; however, the sector recorded only marginal growth of 0.62 per cent during July-November of FY2026. Notably, both the export and remittance sectors were on a negative growth trajectory when the interim government took office.

However in recent months, the export sector has come under mounting pressure amid global headwinds and domestic constraints. These challenges have led to a decline in export earnings for four consecutive months. Although the current fiscal year has not yet recorded an outright contraction, export growth during the July-November period has remained below 1 per cent, underscoring the sector's fragility. Of particular concern is the nearly 14 per cent drop in imports of raw materials for export-oriented industries, a trend that points to weaker production and the risk of further erosion in export earnings in the months ahead.

Domestically, the economy remains sluggish. Political instability persists, with incidents of mob violence becoming more frequent. Even though election schedule has been announced, uncertainty continues to cloud the outlook. Entrepreneurs have adopted a wait-and-see approach, focused largely on keeping existing businesses afloat, rather than venturing into new enterprises. Investment has stalled, job creation has slowed and private sector credit growth fell to a historic low of 6.23 per cent in October 2025, reflecting deep-seated investment weakness.

Another major problem for investors is the steep rise in bank lending rates. A persistently tight monetary policy over the past three years, aimed at reining in inflation, has driven up the lending rate from the previous 9 per cent to around 16 per cent. This has significantly increased the cost of doing business.

Foreign direct investment remains modest at under one per cent of GDP, with both new and existing investors reluctant to commit fresh capital. New investment is virtually absent. This is a major concern as Bangladesh urgently needs investment to diversify its economy, raise productivity and create employment. Without restoring investor confidence by ensuring political stability, upholding the rule of law and providing policy certainty, modest macroeconomic gains alone will not be enough to put the economy on a sustainable growth path.

The banking sector, meanwhile, remains under severe strain. Declining public confidence has made it difficult for several banks to mobilise deposits, while non-performing loans (NPLs) continue to surge. As of September 2025, NPLs accounted for 35.73 per cent of total disbursed loans. Unprecedented plundering of bank capital under the guise of loans during the previous regime bled the sector dry. Although such looting has stopped, its scars are becoming increasingly visible as loans linked to willful defaulters continue to turn non-performing. At the end of the Awami League's tenure, NPLs stood at Tk 1.82 trillion; it has now ballooned to Tk 6.44 trillion - an increase of Tk 4.63 trillion in just over a year. It poses a serious threat to financial stability.

Wide-ranging reforms are now underway across the banking sector and the broader economy, and some early gains are already visible. With an election approaching, the pace of change may slow, but there is a broad consensus among economists and development partners that sustained reform under the next government would make these gains far more tangible.

Atiqul Kabir Tuhin

Published :

Dec 31, 2025 23:17

Updated :

Dec 31, 2025 23:17

As a new year dawns, an economic post-mortem of the bygone year reflects a story of resilience, reform and recalibration. While public expectations were sky-high at the outset of the interim government, the economy failed to stage a decisive turnaround over the past one and a half years. Nevertheless, a degree of macroeconomic stability has been achieved. Fiscal discipline has been partially restored, along with tighter oversight of the financial sector. The exchange rate has stabilised, and the dollar crisis has largely been brought under control. Inflation has begun to ease, although it remains stubbornly high and continues to erode purchasing power.

However, the most critical driver of economic recovery - investor confidence - has not been restored. The prolonged crisis of trust continues to dampen investment and business sentiment. Political unrest and uncertainty have not subsided. Rather, volatility has intensified. Recent incidents of vandalism targeting private institutions by radical elements, carried out through 'mob justice', have further undermined stability. Therefore, in 2026, maintaining political stability, restoring investor confidence and carrying forward the reform initiatives will be some of the formidable challenges on the economic front.

On the external front, the picture is comparatively brighter. A range of policy measures over the past 18 months has brought considerable relief to the balance of payments. Capital flight appears to have declined significantly. Meanwhile, a sharp rise in remittance inflows, coupled with a modest increase in export earnings, has boosted the supply of dollars in the market. As a result, local currency taka gained strength against dollar. However, authorities have refrained from lowering the dollar price too aggressively to sustain remittance and export growth. Improved dollar liquidity has also reduced the appetite for high-interest foreign borrowing. All recent government loans from external sources have been on concessional terms.

During Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian regime, there were widespread allegations that remittances and export proceeds were diverted through hundi. Moreover, large sums of money were siphoned off under the guise of imports. As a result, the country's foreign exchange reserves were in a free fall. Net foreign exchange reserves had declined to $17 billion. The exchange rate peaked at Tk 132 per dollar. Amid a prolonged dollar crisis, the government had even imposed import restrictions and deferred payments on large-scale foreign loans.

Since then, the free fall in foreign exchange reserves has been halted. The exchange rate has stabilised at around Tk 122 per dollar, and reserves have rebounded to nearly $28 billion. This recovery has been driven mainly by the curbing of looting and money laundering, alongside strong remittance inflows and export growth. Remittances grew by nearly 27 per cent in the last fiscal year and by more than 17 per cent in the current fiscal year up to November. Export earnings increased by 8 per cent in FY2025; however, the sector recorded only marginal growth of 0.62 per cent during July-November of FY2026. Notably, both the export and remittance sectors were on a negative growth trajectory when the interim government took office.

However in recent months, the export sector has come under mounting pressure amid global headwinds and domestic constraints. These challenges have led to a decline in export earnings for four consecutive months. Although the current fiscal year has not yet recorded an outright contraction, export growth during the July-November period has remained below 1 per cent, underscoring the sector's fragility. Of particular concern is the nearly 14 per cent drop in imports of raw materials for export-oriented industries, a trend that points to weaker production and the risk of further erosion in export earnings in the months ahead.

Domestically, the economy remains sluggish. Political instability persists, with incidents of mob violence becoming more frequent. Even though election schedule has been announced, uncertainty continues to cloud the outlook. Entrepreneurs have adopted a wait-and-see approach, focused largely on keeping existing businesses afloat, rather than venturing into new enterprises. Investment has stalled, job creation has slowed and private sector credit growth fell to a historic low of 6.23 per cent in October 2025, reflecting deep-seated investment weakness.

Another major problem for investors is the steep rise in bank lending rates. A persistently tight monetary policy over the past three years, aimed at reining in inflation, has driven up the lending rate from the previous 9 per cent to around 16 per cent. This has significantly increased the cost of doing business.

Foreign direct investment remains modest at under one per cent of GDP, with both new and existing investors reluctant to commit fresh capital. New investment is virtually absent. This is a major concern as Bangladesh urgently needs investment to diversify its economy, raise productivity and create employment. Without restoring investor confidence by ensuring political stability, upholding the rule of law and providing policy certainty, modest macroeconomic gains alone will not be enough to put the economy on a sustainable growth path.

The banking sector, meanwhile, remains under severe strain. Declining public confidence has made it difficult for several banks to mobilise deposits, while non-performing loans (NPLs) continue to surge. As of September 2025, NPLs accounted for 35.73 per cent of total disbursed loans. Unprecedented plundering of bank capital under the guise of loans during the previous regime bled the sector dry. Although such looting has stopped, its scars are becoming increasingly visible as loans linked to willful defaulters continue to turn non-performing. At the end of the Awami League's tenure, NPLs stood at Tk 1.82 trillion; it has now ballooned to Tk 6.44 trillion - an increase of Tk 4.63 trillion in just over a year. It poses a serious threat to financial stability.

Wide-ranging reforms are now underway across the banking sector and the broader economy, and some early gains are already visible. With an election approaching, the pace of change may slow, but there is a broad consensus among economists and development partners that sustained reform under the next government would make these gains far more tangible.