‘The interim has failed to curb inflation and unemployment’: A rebuttal

FILE VISUAL: SALMAN SAKIB SHAHRYAR

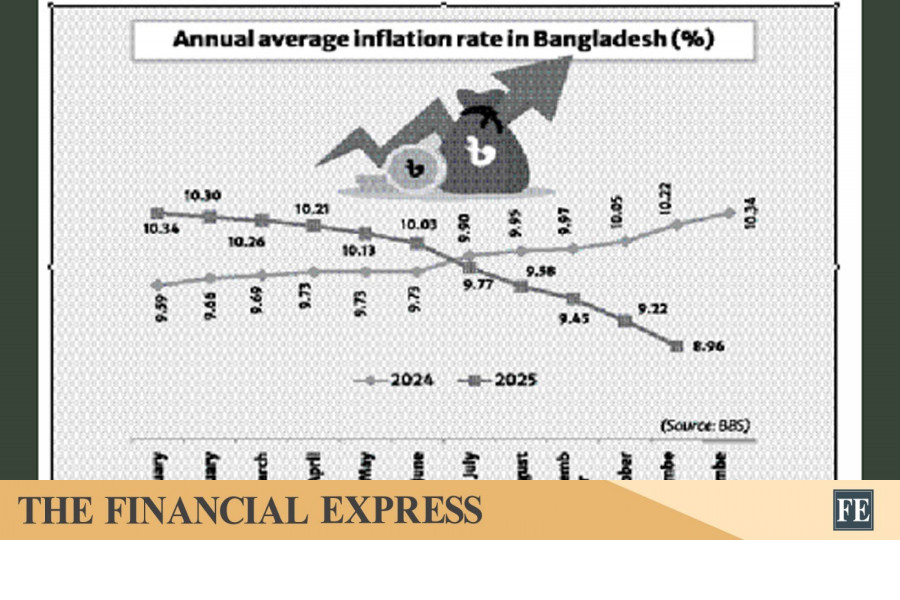

I write this in response to an article recently published by The Daily Star, titled The interim has failed to curb inflation and unemployment. The article, written by Dr Birupaksha Paul, evaluates the interim government's economic performance primarily through the conventional inflation-unemployment trade-off, concluding that policy failure explains the persistence of both. In my view, while the argument is internally coherent in a textbook sense, it rests on analytical assumptions that no longer hold and omits critical institutional realities. These omissions are serious enough to mislead public understanding and, therefore, warrant rebuttal.

One may recall that the interim government assumed responsibility amid a nationwide breakdown of law and order, where weakened enforcement and administrative paralysis disrupted commerce, supply chains, and investor confidence, constraining economic stabilisation at the outset.

The central problem with the article is not its use of economic theory, but its choice of theory and its abstraction from context. It treats Bangladesh's economy as though it were operating under normal macroeconomic conditions, where interest rates transmit smoothly through banks, markets are broadly competitive, and inflation and employment respond predictably to policy signals. This premise is unfair. The truth is, the interim government inherited an economy marked by deep financial-sector impairment, excess liquidity without accountability, cartelised supply chains, and severely weakened regulatory credibility. Any assessment that ignores this inheritance risks confusing structural damage with contemporaneous policy failure.

The article's analytical backbone is the inflation-unemployment trade-off commonly associated with the Phillips curve. This framework, once influential in mid-20th-century industrial economies, has long lost empirical relevance in modern economic systems. Over the past four decades, the Phillips curve has flattened or broken down across both advanced and developing economies. Low unemployment has frequently coexisted with stable inflation, while inflationary episodes have occurred without tight labour markets. This is not a temporary anomaly but a structural shift in how inflation and employment are generated in contemporary economies.

Modern inflation is no longer driven primarily by domestic demand pressures interacting with labour scarcity. It is increasingly shaped by supply-side shocks, exchange-rate pass-through, energy and commodity price volatility, market concentration, administered pricing, speculative behaviour, and institutional failures. In Bangladesh's case, syndicate control over essential commodities and distribution networks has played a decisive role in price formation. When inflation is driven by market power rather than excess demand, monetary tightening becomes largely ineffective. Raising interest rates does not dismantle cartels or discipline supply-chain manipulation. The article in question does not engage with this distinction, yet it is central to understanding why inflation has proved persistent during the interim period.

Unemployment, likewise, has become structurally decoupled from short-run monetary adjustments. Employment outcomes today depend far more on investment confidence, financial-sector health, regulatory predictability, and credit availability than on marginal changes in policy interest rates. Firms do not hire because rates move slightly; they hire when they trust banks, contracts, competition policy, credible enforcement against cartels and syndicates, and the broader institutional environment. An economy emerging from years of politically protected loan default, balance-sheet opacity, and regulatory erosion cannot generate employment through textbook stimulus channels. The article's framing obscures these realities by attributing employment outcomes primarily to the interest-rate policy.

A further weakness lies in the article's treatment of monetary policy transmission as intact. The Phillips-curve logic presumes a functioning banking system capable of translating policy signals into credit allocation. But Bangladesh's banking sector, at the time the interim government took over, was severely compromised. Large volumes of liquidity circulated outside productive channels. Loan discipline had been eroded, supervision weakened, and public confidence damaged. Under such conditions, neither tightening nor easing operates cleanly. Monetary policy becomes a blunt instrument, producing weak, delayed, or perverse effects. Evaluating outcomes as if transmission were normal is analytically unsound.

The article also fails to distinguish between policy optimisation and crisis stabilisation. Interim governments do not inherit clean slates; they inherit trajectories. Their primary task is to arrest deterioration, prevent systemic collapse, and restore minimal functionality. Expecting simultaneous reductions in inflation and unemployment within a short horizon—using non-crisis macroeconomic benchmarks—imposes an unrealistic standard. Even advanced economies with intact institutions experience long and uneven lags between policy action and labour-market outcomes. In Bangladesh's case, those lags are longer because institutional damage had to be addressed before policy levers could regain effectiveness.

Another notable omission is the absence of temporal analysis. The article implicitly treats outcomes as contemporaneous products of interim decisions, rather than as lagged consequences of earlier distortions. Inflationary momentum, excess liquidity, and investment paralysis do not dissipate instantly when governance changes. They unwind slowly, often asymmetrically. By ignoring these dynamics, the article compresses time and assigns responsibility without acknowledging deeply rooted institutional inertia.

Of course, none of this implies that the interim government should be immune from criticism. In fact, criticism is both necessary and appropriate where warranted. But accountability requires proportionality and analytical precision. Criticism grounded in outdated frameworks and incomplete context does not enhance public understanding. When economics is stripped of institutional realism, it risks becoming elegant but misleading. The issue here is not whether inflation and unemployment has declined fast enough, but whether the analytical lens used to judge performance is appropriate to the reality being assessed. Applying a mid-20th-century trade-off model to a 21st-century economy marked by financial fragility, market capture, and governance breakdown is a category error. It evaluates the patient with the wrong diagnostic tool.

A more credible assessment would begin with what the interim government inherited: a weakened banking system, distorted markets, eroded regulatory credibility, and broken transmission mechanisms. It would then ask whether deterioration was halted, whether minimal discipline was restored, and whether conditions for future policy effectiveness began to re-emerge. Only after those foundations are rebuilt does it make sense to judge performance against conventional macroeconomic benchmarks.

This is why a rebuttal is necessary. My disagreement here is not ideological but analytical. Inflation and unemployment today are multi-causal, institutionally mediated, and globally augmented phenomena. Treating them as mechanically linked through an obsolete curve risks mistaking inherited structural decay for present-day policy failure. A serious public debate deserves better diagnostic tools and better contextualisation.

Dr Abdullah A. Dewan is professor emeritus of economics at Eastern Michigan University, USA, and former physicist and nuclear engineer at Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission.

akijbashir.com

Just a few videos will give everyone some idea of how refined their manufacturing approach is, clearly some of the finest operations in South Asia and price competitive to boot for global exports.

akijbashir.com

Just a few videos will give everyone some idea of how refined their manufacturing approach is, clearly some of the finest operations in South Asia and price competitive to boot for global exports.

akijbashir.com

akijbashir.com